Investigation shows how far Idaho’s needle exchange program strayed before police raid

Idaho Health and Welfare’s internal review — which was announced after the Idaho Harm Reduction Project’s offices were raided by police — discovered a “distinct disconnect” between leadership and the staff members operating the syringe exchange program, according to an investigative report obtained by the Idaho Statesman.

Controversy surrounding Idaho’s needle exchange programs began earlier this year after the Boise Police Department served search warrants on the Idaho Harm Reduction Project’s Boise and Caldwell offices, seizing packaged drug paraphernalia as part of an investigation into their distribution. Police have declined to provide additional information.

Idaho Harm Reduction Project, a nonprofit that received funding from Health and Welfare, offered a variety of services, including a legal needle exchange program and medical services such as STI, HIV and Hepatitis C testing. Several other organizations throughout the state offer similar services, including the safer-syringe program.

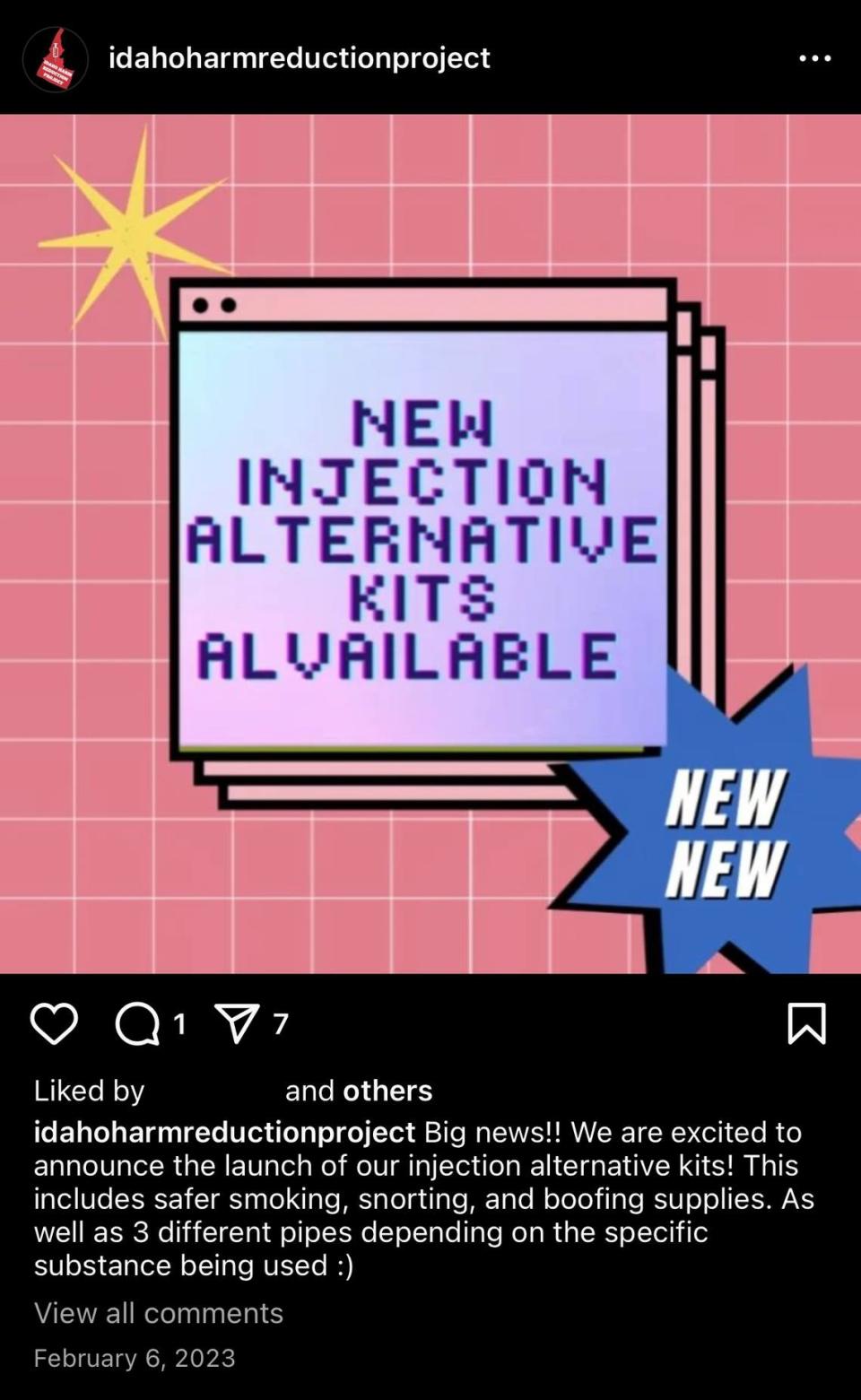

In the ensuing month, it was discovered by the Statesman that employees from Idaho Harm Reduction Project admitted during a September conference to illegally distributing the packaged drug items — which included snorting kits, bubble pipes that are used for methamphetamine, and heroin pipes, commonly referred to as hammers. Lawmakers challenged the necessity of needle exchange programs, repealing the law that legalized the program in the first place. The Idaho Harm Reduction Project has closed.

The eight-week Health and Welfare internal investigation — prompted by Gov. Brad Little — found that while the agency didn’t directly purchase pipes, it did in “some cases” reimburse needle exchange programs for their purchases, according to an 11-page report, which found implied support for purchasing pipes or other injection alternatives.

The report was provided to the Statesman upon request by Health and Welfare.

Based on emails, along with the conference presentation, Health and Welfare also determined that the Idaho Harm Reduction Project handed out injection-alternative kits that included drug paraphernalia and an instruction card on how to use specific drugs safely.

Not all of the safer-syringe programs gave out injection alternatives, the report added.

As part of its review, Health and Welfare implemented a smattering of recommendations and saw the resignation of a “key” employee who supported the program, according to the report. Health and Welfare said it reviewed over 6,000 emails, interviewed employees, researched needle exchange programs, conducted on-site visits to five needle exchange programs, and reviewed contracts, training, grants and other related documents.

The agency added training, plans to review its oversight practices especially for “politically sensitive” programs, and is requiring employees to watch legislative hearings regarding the programs they manage. Additionally, Health and Welfare ended its contract with the Idaho Harm Reduction Project but will resume funding and support to other programs until the Needle Exchange Act is repealed in July.

“The review revealed many opportunities for improvement and reaffirmed the importance of some endeavors DHW already had underway,” Health and Welfare Interim Director Dean Cameron said.

Little called the investigation an “intensive review” that “fully uncovered” what happened, according to a letter acknowledging the completion of the investigation, which the Statesman also obtained from Health and Welfare. He thanked Cameron for the “prompt and thorough” attention and said he felt confident the agency took “appropriate, decisive and corrective actions.”

“We are proud that Idaho’s laws stand strongly against illegal drug use,” Little wrote in the letter. “Idaho is not Seattle, San Francisco and Left Coast states that condone and support drug use.”

Health and Welfare reimbursed exchange program purchases

Health and Welfare Program Manager Monica Young said in the report that the passage of the Needle Exchange Act in 2019, which allowed people to obtain clean needles through the exchange program, permitted employees to obtain “supplies” that they needed to operate their programs but didn’t define supplies.

This left employees to question what was appropriate to purchase, she said, adding that Health and Welfare staff didn’t ask leadership for “direction or clarity.” Young was directed to conduct the review by Cameron.

Needles, along with pipes, were never decriminalized as paraphernalia, which means people can still be charged with possession of drug paraphernalia. Research has pointed to smoking being a safer alternative to using drugs than injecting.

Health and Welfare’s leadership was “unaware” that injection alternatives like pipes, along with fentanyl strips and cookers, were being reimbursed, and endorsed by Health and Welfare staff, according to the report. Cookers are containers used to prepare drugs before injecting them that are commonly given out in needle exchange programs.

It’s unclear how often these items were reimbursed as many of the invoices — particularly from the Idaho Harm Reduction Project — lacked specific details, the report said. This is something Cameron identified during a legislative committee meeting as an area where Health and Welfare could improve, adding that the agency plans to provide more detailed invoices going forward.

A staff member from the Idaho Harm Reduction Project said during the conference that the health department was supportive when it came to the syringe program, but for the alternatives, the group used funding from grants and other donors.

In one instance early into the program implementation, Health and Welfare staff directly purchased $516 worth of cookers but didn’t continue doing so as they weren’t sure if that was allowed. There were also concerns that federal funds might have been “inappropriately” used to reimburse cooker purchases, the report said.

All of the organizations that Health and Welfare visited had been operating for decades before needle exchange was legalized, offering other harm reduction services including testing and therapy, and providing a food pantry and free clothing. Those programs told Health and Welfare that they work with community organizations, including law enforcement, and have been operating legally.

Young said Health and Welfare wasn’t able to visit the Idaho Harm Reduction Project because the organization closed its doors after the raid. Attempts to contact the Harm Reduction Project by the Statesman have been unsuccessful.

The division came between Health and Welfare program staff, who believed that legalizing needle exchange meant that evidence-based harm reduction methods were appropriate, and leadership who thought the state only legalized the exchange and wasn’t providing an “endorsement for widespread harm reduction activities,” according to the report. Young added that the independence and decision-making by the syringe program staff members was “unprecedented.”

“I speculate that with the syringe exchange program beginning at the onset of the pandemic, leadership was focused on statewide pandemic response rather than (safer-syringe programs) operational details,” Young wrote, “leading to an environment where the inconsistent interpretations manifested other challenges.”

Expert: Safer smoking supplies can reduce injection use

There was also a concern outlined in the report that Health and Welfare staff printed documents for the Harm Reduction Project.

Health and Welfare previously confirmed that a state employee, who the agency declined to identify, printed pamphlets for the Idaho Harm Reduction Project that detailed step-by-step instructions on how to safely use several drugs. That’s something that the agency’s leadership does not “support” or “condone,” Health and Welfare spokesperson Greg Stahl said.

“If leadership had known, they would not have been approved,” he added.

But Brown University School of Public Health Professor Brandon Marshall told the Statesman that the distribution of harm reduction products like pipes along with instructions in “plain” and “clear” language is considered best practice.

“This is really important because injecting drugs is linked with much higher rates of overdose, skin and soft-tissue infections and hospitalizations,” Marshall said in a phone interview. “So increasingly,distributing safer-smoking supplies is seen as a way to help people transition away from injecting and towards a safer mode of use.”

Additionally, smoking substances comes with its own adverse health risks, so people should have access to clean equipment, he said.

With the rise of fentanyl-laced drugs, Marshall said, the risk of overdose is “higher than it’s ever been,” especially for people who might not have used drugs as frequently or are transitioning the way they use drugs.

“It’s more important than ever to be expanding harm reduction programs and to be reaching people who are at risk for overdose across the country — but in some Western locations in particular,” Marshall said, referring to the increase of certain drug use throughout the West.

Some states — including Rhode Island, where Marshall is located — have fully legalized the distribution of drug paraphernalia, along with items like fentanyl test strips. Other states have what Marshall called a “patchwork” of laws at a local level.

Marshall said he’s concerned about the risk of HIV outbreaks in Idaho, pointing to a study he conducted that found shuttering syringe programs increases the risk of an outbreak by as much as 60% among people who inject drugs. He added that the closure of harm reduction programs isn’t unique to Idaho, despite the unprecedented federal support for the programs from the Biden administration.

“Yet in some places, we are seeing pushback and I think a lot of that comes from a lack of understanding of what these programs aim to do, their public health benefits, and then all the misconceptions about what they are doing,” Marshall said.