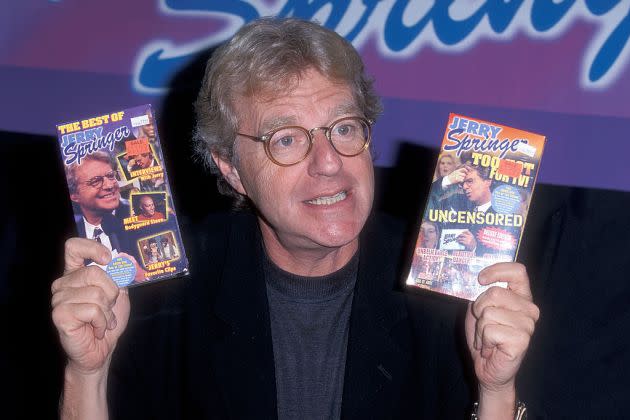

Jerry Springer, Ringmaster of Pugilistic Talk-Show Circus, Dead at 79

Jerry Springer, the controversial and influential talk-show host who fused chaos and entertainment while showcasing the underbelly of America on daytime television, died Thursday at the age of 79.

Springer’s family confirmed his death in a statement to Rolling Stone, noting that he died peacefully at his home in the suburbs of Chicago; while no cause of death was provided, it was reported recently that Springer had been diagnosed with cancer.

More from Rolling Stone

Farewell Jerry Springer, the Patron Saint of American Dysfunction

Harry Belafonte, Legendary Entertainer and Activist, Dead at 96

Songwriter Keith Gattis, Whose Songs Were Cut by Kenny Chesney and George Strait, Dead at 52

“Jerry’s ability to connect with people was at the heart of his success in everything he tried, whether that was politics, broadcasting, or just joking with people on the street who wanted a photo or a word,” Jene Galvin, a lifelong friend and spokesman for the family, said in a statement. “He’s irreplaceable, and his loss hurts immensely, but memories of his intellect, heart, and humor will live on.”

Galvin added, “To remember Jerry, the family asks that in lieu of flowers you consider following his spirit and make a donation or commit to an act of kindness to someone in need or a worthy advocacy organization. As he always said, ‘Take care of yourself, and each other.'”

Prior to becoming daytime television’s most notorious personality, Springer had a more modest start in the public eye as mayor of Cincinnati in 1977. Springer’s own life story was just as shocking as any brawl-fueling revelation he oversaw on his TV show: He was born in 1944 in a London tube station turned bomb shelter, the son of Jewish refugees from Prussia escaping the Holocaust.

Springer and his family immigrated to Queens, New York, when he was four years old. He went to college at Tulane, but law school brought him to Northwestern University in Chicago, the city where he’d spend the majority of his life.

Before all the chair-throwing and hair-pulling of his TV show, Springer entered another bloodsport: politics. He first worked on Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign, and upon joining a Cincinnati law firm, ran for public office in Ohio, first with a failed bid for Congress in 1970, followed by a successful run for Cincinnati City Council. Springer ultimately served a one-year, council-appointed term as mayor of Cincinnati in 1977. A Democratic gubernatorial run followed in 1982, but Springer failed to land the party’s nomination.

While still politically active, Springer — who worked as a student journalist and broadcaster while at Tulane — began to embark on a different kind of career in front of the camera, first as a political reporter with local news programs, before becoming the news anchor for Cincinnati’s WLWT; during his tenure behind the news desk, Springer coined the phrase that he would eventually bring to syndication for decades: “Take care of yourself, and each other.”

In 1991, Springer began hosting his own daytime talk show, aptly titled Jerry Springer, on WLWT, a program inspired by The Phil Donahue Show and The Oprah Winfrey Show. Like those programs, Springer tackled current affairs, as well as some more taboo topics: In one early episode, Springer interviewed the infamous punk rocker G.G. Allin, a “violent and obscene rock musician,” about the effects that rock music has on impressionable young minds. However, it was an actual talk show compared with what the programming would soon devolve into.

After one year in Cincinnati, Jerry Springer moved to its longtime home of Chicago, a relocation that brought a demand for higher ratings and a subsequent turn toward the more salacious, violent, and controversial subject matter that would define the show. Brawls between guests were orchestrated and a near-daily occurrence. Episodes would feature bizarro themes like “I Married a Horse,” “My Virgin Sister Wants My Man,” and “I Cheated 40 Times.” Within a few years, with the audience’s “Jerry! Jerry! Jerry!” its clarion call, discourse was dead at Jerry Springer, and deviance had taken rise.

“What has happened is a total shock,” Springer told Rolling Stone in 1998, with his show already a cultural phenomenon; a film starring Springer titled Ringmaster, inspired by the talk show, would be released in theaters that same year.

“I have no training in this. No particular talent. Someone signed me. I didn’t even try out. So I got lucky and I’m a schlub with a show,” Springer told Rolling Stone. “There are millions of people that can do it better. But, well, I happen to have the job I have, and now the show has taken off and I’m going along for the ride. I’m loving it. But I can’t, with a straight face, tell you, ‘Boy, I’ve figured this all out, and I’m just a genius!’ I have no idea. I don’t get it. I really just don’t. And I’d love to know.” (Springer appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, with the headline touting “Jerry Springer: Sex, Sin and the Death of All We Hold Sacred.”)

Summarizing his own show, Springer said, “It’s chewing gum, it’s silly, it’s outrageous, it’s stupid, it’s a spoof, it’s a fraternity party on the air, it’s crazy.… These people aren’t committing crimes. They’re yelling at each other. If anything, they’re coming out and being honest. If someone’s cheating and saying, ‘Hey, I’m cheating,’ what’s the crime in that?”

Springer also pontificated on appealing to a different type of TV viewer. “I mean, American television is so upper white middle class,” he said. “On mainstream television, that’s the only perspective we see. And so here you have a show that just defies all these traditions, where the people on it don’t speak the king’s English, they’re not rich or powerful, and most of them don’t have an education. But the critics don’t want to see that. And that’s very, very elitist.”

For 27 seasons, Jerry Springer aired on television, though a string of copycats it inspired — Maury, the The Steve Wilkos Show (the latter starring Springer’s hulking security guard, in his own spinoff) — and the overall bar-lowering of America softened its bite. Springer ultimately ended his reign as daytime TV’s trash king in 2018.

“Other than my father, Jerry was the most influential man in my life,” Wilkos said Thursday in a statement to Rolling Stone. “Everything I have today I owe to Jerry. He was the smartest, most generous, kindest person I’ve ever known. My wife and I are devastated. We will miss him terribly.”

As himself, Springer also appeared in films like Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (where he reunited Dr. Evil and his son on an episode of Jerry Springer) and Meet Wally Sparks, as well as guest-starring roles on The X-Files, The Wayans Bros., George Lopez, Roseanne, Married… With Children, and more.

Springer would remain in the periphery of the public eye — a judge on America’s Got Talent and his Judge Jerry, a contestant on Dancing With the Stars and The Masked Singer, his own podcast — before he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

“What I’ve learned over our quarter-century of shows is that deep down, we are all alike. Some of us just dress better, or had a better education, or better luck of parents,” Springer said on his show’s 25th-anniversary episode.

“I’ll say it again: Deep down, we are all the same. We all want to be happy. We cry when we’re hurt, we’re angry when we’ve been mistreated. And to be liked, accepted, and respected — not to mention loved — is the greatest gift of all. Know this: There’s never been a moment in the 25 years of doing this show that I ever thought I was better than the people appearing on our stage. I’m not better; only luckier.”

Springer concluded, “And on that note, ‘Take care of yourself, and each other.'”

Best of Rolling Stone