Life after prison brought him nothing but shut doors. He wants others to have it better

Editor’s Note: This interview is part of he second season of Voices of Kansas City, a project created in collaboration with KKFI Community Radio to highlight the experiences of Kansas Citians making an impact on the community. Hear the interviews at 6 p.m. Wednesdays on KKFI 90.1 FM, or at KKFI.org. Do you know someone who should be featured in a future season of Voices of Kansas City? Tell us about them using this form.

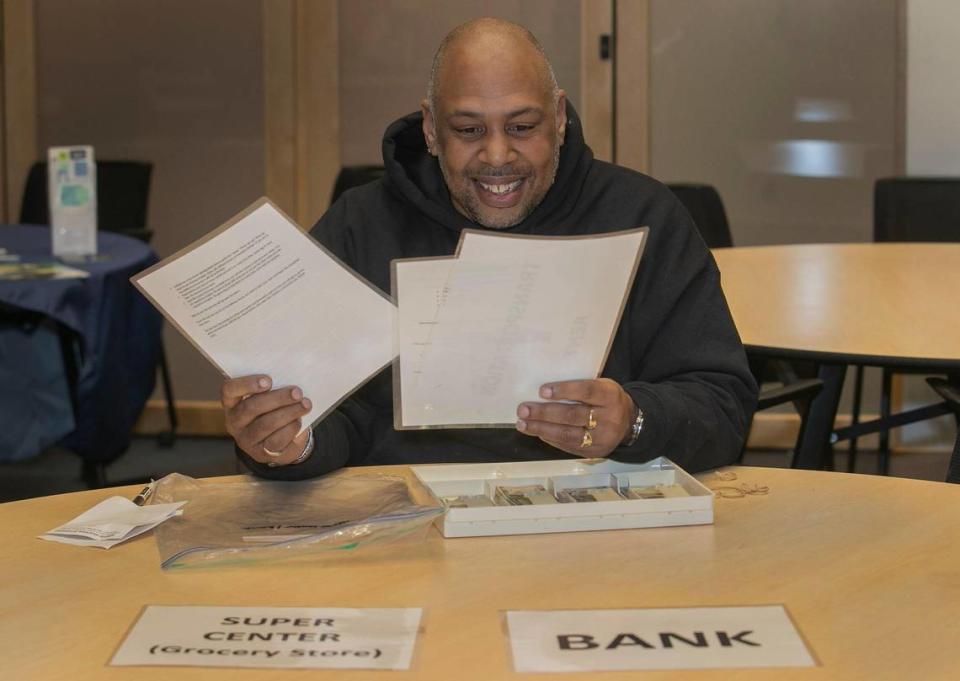

It seems as though Johnny Waller, a local activist who touts the motto “dream big,” is always smiling. It’s as if he knows a little bit more about life — the good side and the bad side — than others do, and he’s happy to now be living on the good side.

That was not always the case.

As a teen Waller spent several years in prison. When he got out there weren’t a lot of opportunities coming his way. But, he refused to give up on turning his life around. Today, knowing what he does about the challenges faced by the formerly incarcerated, even after they’ve served their time behind bars, Waller is passionate about helping those men and women clear their records and seek second chances at becoming productive citizens.

The Star invited Waller to join us in the studios of KKFI radio to share his story of redemption and his fight for legislative changes that would help people who have served their time in prison return to society in a productive way. He recently spoke to Mará Rose Williams, The Star’s assistant managing editor for race and equity. That interview, with minor editing for space and clarity, is published here in a question and answer format to share Waller’s authentic voice.

Meet Johnny Waller

The Star: So I know that you are involved with expungement and second chances and words like that. I know what all those things mean, but can you tell us more about what your advocacy is. What is your activism?

Yeah. So expungement is a process that you go through here in Missouri under legislation. 610 140. And it pretty much is supposed to seal someone with a criminal records background. And so we do the expungement project to help people clear their background. There’s 1.8 million people in Missouri who have a criminal record. And so we want to help seal them so they can move forward with their life.

So are we talking about people who, you know, have too many parking tickets or are we talking about people who maybe committed a felony?

We’re talking about not so much traffic tickets, but people who have more serious misdemeanors. And then, of course, yes, felony convictions like possession (of drugs) and possession with intent or something of that magnitude. Stealing, forgery, those type of crimes.

So when you say we do this and we do that, who’s the we you’re talking about?

So we have a team of me, a former dean, Ellen Suni, who was like the eighth longest serving dean at the UMKC (University of Missouri-Kansas City) Law School. It’s a bunch of us.

Does the group have a specific name or is it just a group of like-minded activists who come together to do this work?

Well, the group is called the CMA, which is the Clear My Record project. It is currently winding down and is in transition of moving out of UMKC so we can find it a different home. But it was started by pretty much a brainchild of Dean Suni, who had been in this work for a very long time.

And do you get a lot of people coming in? Tell me how it works. What do you do?

So normally people would search out for the word expungement. So when you talk about mass incarceration there are a lot of people with criminal records. So a lot of people get online and the Google search or word of mouth. Especially after people have been denied housing, or denied employment, or food stamps or whatever assistance that they need. So they will either look it up or ask somebody or go to a community organization and they will normally point them towards the expungement clinic because at the time, it was the only like expungement clinic that was free for people who qualify in the income level.

So basically you’re sealing their criminal record. So let’s say if I had some misdemeanor or felony in my history and I came to you, got that expunged and then went for a job, would I have to answer the question, “Have you ever been convicted of a felony,” yes? Or can I answer that question no since it’s been expunged?

You could answer no.

I could answer no. And there would be no penalty for that?

No, absolutely not.

So expungement just gets rid of it altogether.

It’s supposed to. Absolutely.

Why did you say it’s supposed to?

Well, so there’s some caveats, when people run background checks. As you know, there’s a lot of companies out here who do third-party background checks and they may scrape information, and the information may be old. And it’ll still be on there or in some cases when it comes back, they might put the word, like, “expunged” next to it. Like I received a pardon and when my background was checked it just came back and said, “Johnny Waller, pardon.” And I was like, “Yeah, that doesn’t do me much good because it’s still there.” So I’m still trying to expand the legislation and work it out to where when people actually do get an expungement, that it’s no longer visible to anybody, including those who scraped third-party information or don’t update their database, because it’ll still reflect that that person has a criminal record.

You talked about a pardon for yourself. And so I really want to get to that. But before I even go that far, let me find out a little bit more about Johnny. So are you a native of Kansas City?

No, I’m originally from Omaha, Nebraska.

Did you grow up in Omaha? Did you grow up in Kansas City?

I grew up in Omaha and I came to Kansas City probably when I was 20 years old.

Tell me a little bit about your upbringing. What was that like?

Well, it wasn’t glorious. So I grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, and so my neighborhood was pretty gang infested. And it turned out I experienced some homelessness when I was young. I joined a gang, got into some altercations and got into a shootout, eventually got shot in the head. And when I was 18 years old, my goodness, I ended up in prison.

You ended up in prison? What were you in prison for?

Possession and possession with intent to distribute.

Drugs?

Yeah, distribution.

How long were you there?

I got two and a half to five years and 18 months.

Wow. You said two and a half to five years.

Yeah.

So how many years did you serve?

I did about three years. I went to the parole board. And they said you can get parole as long as you leave the state.

And that was to leave Omaha.

Yeah. Yeah, I had to leave Omaha.

How old were you?

I went to prison when I was 18. So I was about 21 and they gave me 24 hours to leave the state.

Pack your bags and get to stepping.

Right? Yeah. And I ended up in Kansas City.

So what did prison do for you? Did it do anything good for you?

No, absolutely not. It was it was a very horrible experience. There’s a lot of violence, a lot of abuse — whether that’s physical abuse, sexual abuse, things. I was a kid. I was like 18. So I didn’t really understand the dynamics of prison. But I found out very quickly. And so what I will say is that them sending me out of state probably saved my life.

That was probably the goal. How did you choose Kansas City and why?

Well, my mother had moved down here, and so that was probably the only reason. At this point my dad, he’d been smoking crack for, I don’t know how long, since probably I was 11 years old or something. And so that wasn’t an option. And my mom had moved to Kansas City and so she was like, “You know, you can come down here.”

And so you get to Kansas City and what do you do with yourself here?

Well, I try to, I tried to change my life at first and I applied for probably about 176 jobs. Didn’t get any. Try to go to school. First they told me I couldn’t get financial aid because I had a felony drug conviction. You know, I tried to get a place to live. They told me no because I had a felony conviction. And so it really became this thing of, like I really couldn’t do anything. Like, I have a bunch of hopes and dreams when I got out, but they were quickly crushed.

It just sounds to me like even if you do your time, it’s like another prison when you get out. There are no opportunities. No doors opening for you.

This, this, this prison out here is way worse. It’s like, it’s like seeing a world in a glass and you’re just stuck outside with your face pressed against it and nobody to let you in. At some point I had asked my mom to ah ... I mean I had went back and got a gun and started doing some other stuff, but I just asked her like, “Hey, can I just go back to prison? Like, I’d rather just go back to prison.”

Do you think that your thought, “I’ll just go back to prison” was a thought unique to you? Or, do you think that others who experience that same kind of thing are in the same mindset: You get out, there are no opportunities, no resources, no doors opening, and you’re thinking, I might as well just go back to prison?

Absolutely. If you look at the recidivism rates across the country, this isn’t unique to Kansas City. That’s why recidivism is so high, because you get out and then you’re expected to do all these things, but you can’t do any of them. And so at that point, what are you supposed to do? If you can’t do anything, what are you supposed to do? And that was the situation that I felt myself.

And what did you do with that?

My mother, strangely enough, she ... well, not strange because she’s my mother. She went up and begged the gas station owner to give me a job. They did. And but again, you know, there is a gas station. They sell liquor and they were like, “You have to go get a liquor license.” And I went downtown and they were like, “Have you been convicted of a felony?”

I said, “Yes.” They were like, “Well, you’re not supposed to have a liquor license.” I said, “Well, listen, this is probably my last straw before something bad happens.” Like I explained the whole situation to them. And they gave me an opportunity and was like hey, I’m not going to say who it was, but they gave me an opportunity and I got a liquor license and then I got a job.

Wow. And that made a difference?

Absolutely. I got to get up and go to work. And it wasn’t that much. I think I was making $8.50 an hour or something like that. But like I had a job. I was making 38 cents a day in prison. You’re making $8.50. And so, you know, I started to have a little hope.

And then tell me what happened. I mean, at some point you must’ve progressed from there.

I did. So I got that job and I’m still trying to go to school at this time. And it’s barrier after barrier. First is the drug thing. Then it was that I didn’t sign up for the Selective Service when I was 18 years old, and I said I was — I never went to high school, never graduated high school.

And I’m like, ”I didn’t go to high school.” And when I was 18, I was in prison. And no one in prison said, “Hey, sign up for the Selective Service.” So I didn’t know that this is what you had to do. And so I went to go get another job and a guy — he has since passed on — Jimmy Woodley, with Woodley Building Maintenance, he was like, “Johnny, don’t work for me. You can own a business.” I said, “No, I can’t.” He’s like, “Yes, you can.” I said, “No, I can’t.” He’s like, “Shut up. Listen to me. Do this and you can own a business.” And I started a cleaning company.

Wow. And are you going to school? Did you get in?

No, I’m still not in school yet because there’s still this ... it’s called a status request letter. You have to send it to the Selective Service. And you have to prove why (you did not sign up). And for me, it was easy because I’m like, there’s a Nebraska inmate locator. My prison number is 51451.

I’m on the phone with the lady and she puts it in (the computer). She’s like, “Johnny, Waller? That’s you?” I said, “Yes. I mean, is it really that simple?” And and it took them a long time, so I couldn’t go to school during this time because I couldn’t receive financial aid.

When did you finally get the opportunity to go to school?

2013.

Whoa! In 2013?

Yeah.

And you had been trying since when? When did you come out of prison?

I had been trying for 11 years.

It took you 11 years to get an opportunity to go to school?

Absolutely. Because at first it was I couldn’t get financial aid because if you had felony drug convictions they wouldn’t give you financial aid, period. So I had to wait for the law to change, which took a couple of years. Then it was the status request letter. And that took a while. So it took me over a decade just to go to community college. I went to community college.

And is that the only education you have? I assume you graduated from community college.

No. I have an associate’s degree from Johnson County Community College. I have a bachelor’s degree from Rockhurst University. And then I went back and got a master’s degree in organizational leadership and development from Rockhurst University.

Wow. That is awesome. I guess that long wait really made you hungry for it, right?

It did. Like, you know, not going to high school and all of these things, when I was finally allowed — and it’s crazy to say allowed the opportunity to go to school — I went and when I went, I spent five consecutive semesters at Johnson County on the dean’s list. I got an academic scholarship.

That’s how I went to Rockhurst, on an academic scholarship. And so, yeah, I was pretty hungry. It took me a long time just to be able to get educated.

And were you going to school while you maintained your job, your cleaning company?

Well, no. By the time I got into school I had closed my cleaning company because in between I had my son. When he was 2 years old, he was diagnosed with Stage 4, high risk neuroblastoma. Well, he was probably about 1 and a half. And so I had to move to Memphis, Tennessee, to go to St. Jude Hospital.

We had to stay there. So I lived there for a while. And unfortunately, my son, he caught a cold. He didn’t have an immune system and he passed away five days before his fourth birthday.

I’m so sorry.

Thank you. And so I ended up closing my business. But I promised my son before he passed away that I would finish school. Like I’m going to finish school.

And so that’s kind of how I got on that journey. But I was working full time actually teaching workshop classes to returning citizens on a daily basis down in the historic Lincoln Building. So I’m working full time and then I’m going to school full time. I’m, like, taking 18 credit hours and working a full-time job.

You said returning citizens. Do you mean people who had formerly been incarcerated?

That’s correct. Yeah.

OK. So you have this education, this lived experience. And with that, do you turn that into what has become your advocacy, what has become your activism?

Absolutely. Yeah. So during this course of time I was introduced to Laura McDonald at More2 (the Metro Organization for Racial and Economic Equity) and at first, you know, anyone who knows Laura McDonald (president of More2), she was like “let’s change the law.” And I’m like, what, what are you talking about? So people with drug convictions aren’t able to get food assistance, and that’s just people with drug convictions.

What? That sounds crazy to me.

Yes, it really is. And so we worked six long years on this provision to allow people to get food assistance who had felony convictions.

And you did that when?

That was right after my son passed away and while I was going to school. So that was probably 2013, 2014, something like that.

And so you got that law changed?

Yes, we did.

And I bet that just made you like, OK, what else can we do now? What other kind of law can we get changed?

Yeah, it did. It started this, this journey.

And then we started doing ban the boxes (policies that make employers look at a job candidate’s qualifications first, and only ask about criminal history later). And then I start, you know, doing some other work for returning citizens. And it really just started the ball rolling because I never thought I didn’t know what community organizing was or activism. I didn’t know any of that. Right. Like I’m, I was from the neighborhood.

And so this was all new and fascinating. I’m like, “We can do what? And people are going to listen? And we could change stuff? And so that’s kind of how I started.

I do like that you say returning citizens. That’s a term I had not heard before. I had always heard folks referred to as formerly incarcerated. Is that now defunct terminology? Is the new terminology returning citizens?

I mean, there’s this thing where the language kind of changes, whether that’s formerly incarcerated people or returning citizens. So we kind of use them interchangeably. We try to stay away from words like convict or ex-con or felon because they have this negative connotation, you know. And so people will put you in a box. And so we try to use returning citizen or formerly incarcerated person.

Do you think that people today are beginning to become more receptive to the idea of returning citizenship and being more supportive of helping people like yourself get that shot they need to turn their lives around and to make a difference and to become full and active, wonderful citizens.

Yeah, I think I’ve seen a shift in people, you know. So I gave this presentation to the Missouri Foundation for Health on systems change, and part of it is about mental models and narratives. And so I could see some of the narratives changing. Like, you know, we at some point have to stop incarcerating so many people. At some point we have to start giving people jobs. And we have to start giving people housing. And the Department of Corrections was the first organization to sign up to this 20-30 release model ( a jobs initiative for men and women reentering society from incarceration) too, where they set standards. Like this many people have to get jobs ... And so it’s kind of shifting. I believe it’s because we’re realizing that we incarcerate way too many people.

Yes. And a large percent of them are people of color, young men of color.

Absolutely.

When you and I talked earlier, you were telling me about some grassroots kind of community activism that you’re involved in, in helping people get to expungement clinics held in various locations around Kansas City.

I think you do one at Rockhurst University. You’re a very busy man. Can you tell me a little bit more about those functions, what those things are?

Yeah. So of course I have an office at GIFT, which is Generating Income For Tomorrow. And so we’ve been able to take people who have been formerly incarcerated, had some form of trouble and turn them into businesses. And so I tell people I found freedom through entrepreneurialism. And so that’s why I own a business now. And so I try to help people do that.

So, I have an office at Uncornered. We do violence prevention and work directly with people who normally people wouldn’t work with, and we provide them the resources and help that they need.

I want to stop you there with Uncornered. They are a violence disrupting organization and group, right? Can you talk just a little bit more about what it does?

So, as I previously stated, I was boxed in, in a corner. And so Uncornered is about how you release the potential in individuals such as myself. And so there’s a very uncornered model that we all use to help people discover who they really are. We do that through love, and trust, and building these deep relationships, and letting people know you’re not what people are saying you are. This is the thing that you can be. And so we just unlock the potential of people who normally people say have no potential.

I would think it has something to do with what you were saying earlier about feeling like you had nowhere else to go, and so you were just wanting to go back to prison, which meant maybe committing more crime.

Yeah. What we’re talking about is love. Like I didn’t love myself, I didn’t value myself. I didn’t even know how to value anything. And so I did anything because it didn’t matter. I thought I’d be dead anyway. So it kind of didn’t matter. And then I learned to love myself and then value things.

And then I had stuff. And then everybody wasn’t telling me I was a criminal or a gang member or a thug. People started telling me like, “Hey, you could go do this, and you can go do that.” And for the first time in my life, I believed them. Like, you know what? Maybe I can go do something different. I think that’s important to people, because if you are, you know, if you feel like you’re in a hopeless situation and you don’t value or love yourself, you can’t value or love any, you don’t know how.

And sometimes you need people to help you unlock the potential within yourself so you can go out and do what you are meant to do.

Yeah, I totally get it. What else do you do?

Yeah. Right now I’m working with Municipal Court, shout out to Judge Courtney Wachal, who is the presiding judge. And we’ve been able to do some great things at the municipal level. So right now we’re working on getting some housing resources, getting some mental health resources to people. Hopefully it’ll be where we can get 100 people a month for free for mental health services, jobs, and the clearing of warrants. There are 200,000 outstanding warrants in Kansas City, which is a lot. Judge Wachal on Wednesday, she has a walk-in docket for people who have outstanding warrants so they can go ahead and walk in, get those warrants set aside, get back on the docket so they can take care of their problems.

And then every month we at the Lucile Bluford Branch of the Kansas City Public Library hold the Tap In Center (for individuals in Jackson County, Missouri, who need assistance resolving warrants). And that’s a partnership between us, Municipal Court, public defender’s office and Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker’s office. And we have people come in and we help them clear their warrants or provide resources — in conjunction with the library — they have been a great partner.

I’m working on some housing legislation. Like I said, I met with KC Tenants. And one of the proposals that I did, the Landlord Mitigation Fund, it actually has already passed. So I have got to meet with Councilman (Johnathan) Duncan so we can go through some of that. Then talk to Decarcerate KC about the PAD program, which is a pre-arrest diversion, something that’s been (done) in other cities, including Atlanta.

So shout out to Decarcerate KC. And so you’ll see that coming here very, very shortly. There’s our Housing First Initiative. I wrote the resolution for Kansas City Expungement Day, which is coming up. It’s the first Friday of every June every year. And so I got a lot of stuff going.

Yeah, you’re very busy. But I am hearing a common thread in all that you’re doing. It is all about opening doors so that people who do return to our communities have some avenue for success. It sounds like that would be really fulfilling work. Do you love what you do? Talk to me about the passion.

I do. Let me say first, like I believe the perpetual punishment of people is wrong. Right? And I’ve been made to feel less than a lot of my life due to some mistakes that I made when I was 18 years old. And so, yeah, I love what I do. But more importantly, it benefits the community. I believe there’s an untapped resource that we overlook which are people like me, right?

We have skill sets, we’re knowledgeable, we work hard, we have desire, we have drive. It’s just that we did some things that, you know, in my case, I’m remorseful. When I received my pardon I told them I was guilty and I apologize. That was a different me. I was 18 and so should I be punished for the rest of my life for something that I did when I was 18 years old?

Like, I just don’t think that’s fair. And so now I want to help everybody who has that potential. There’s a million people just like me waiting to get that opportunity, and I don’t believe people should have to go through ...

I’ve got a bunch of degrees and I’ve changed laws, and I’ve done this and I’ve been here and I speak there. And someone shouldn’t have to do all that to live a meaningful life.

And so I’ll take on that burden for them to make sure that they live a meaningful life and their kids can live a meaningful life. And they can find happiness and love and build a family and do all these things that other people take for granted. Like I want people to be able to do that.

I just love what I do and I just want to help people.

Wow, that’s impressive. Here’s a question that I like to ask people. Who is Johnny Waller? You tell me who you are.

You know, I’m a father, brother, lifelong learner. I love the community. I’m an educator and a change agent. That’s kind of who I am. I love comic books, too. So many books and Star Trek. But that’s essentially the core of my being. After my son passed away (at 4 years old), I realized that, you know, life really isn’t promised.

And so I wake up every day with this renewed spirit of “How can I be helpful?” Damon Daniel, who runs Ad Hoc Group Against Crime, told me, “I’m not successful unless you’re successful.” And I’ve carried that. I’ve carried that with me because I want to see my people succeed, right?

Because life is short and I just want to help. I want to be helpful. I want to help people.

How old are you, Mr. Waller?

I am 46 years old.

So you’re going to be around for a long time?

I hope so. I hope so.

Well, thank you for what you do. I really appreciate what you do. And Kansas City should appreciate what you do.

Thank you. I appreciate that. I really do.