How making their mosque safer is helping Quebec City Muslims turn the page on tragedy

When visitors approach the Islamic Cultural Centre in Quebec City's Sainte-Foy neighbourhood, they're no longer greeted by the large picture windows that used to face the street, before a deadly shooting five years ago.

It's been replaced with a concrete wall with smaller windows, in case someone tries to ram the building with a truck.

Security cameras face all the entrances, including the one a gunman used on Jan. 29, 2017, when he walked in and opened fire in a prayer room, killing six worshippers and wounding 19.

Mohamed Khabar had stopped by the mosque that night, as he often did after closing his barbershop. After prayers, he was chatting with friends about soccer: Morocco's loss to Egypt at the Africa Cup of Nations.

"We were talking about … the mistakes the referee and the coaches had made," Khabar said. "We were just chatting about that, when we heard a big noise.''

Khabar says he froze as he watched the gunman shoot at men and children around him. He was shot twice, in the leg and the foot.

As he lay there bleeding he says he thought, this is it. He wouldn't be able to get away if the gunman came closer.

"At that point, I thought of my son who was two months old. I thought of my wife, I thought of my family," he said.

Khabar managed to make it to the stairs with a few others and hopped down on his good leg to the basement, to hide in the electrical room. Still, he feared the gunman would follow his trail of blood.

But the gunman didn't return.

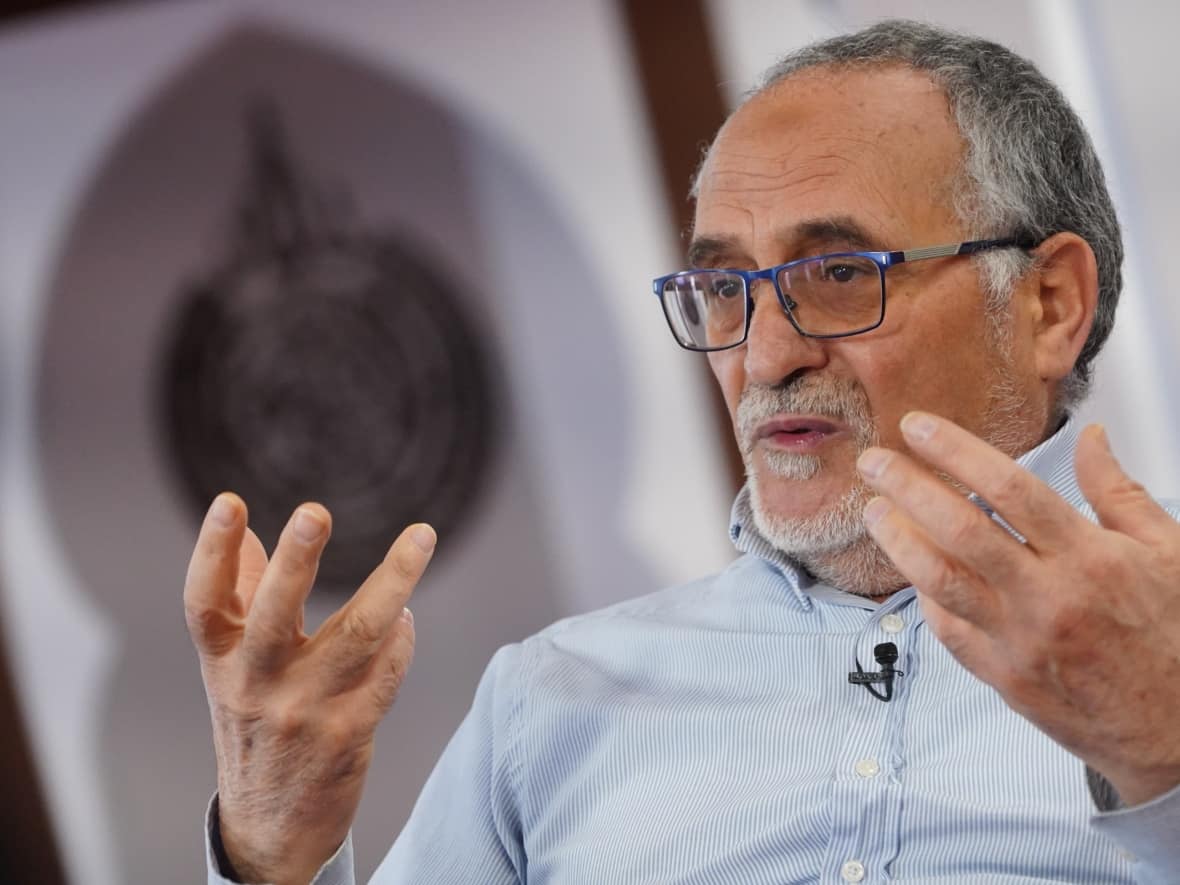

"After the tragedy some people were very afraid to come to the mosque," said Mohamed Labidi, the mosque's past president.

WATCH | Helping worshippers heal:

Even before the shooting, the community had had plans to reinforce the building's security, he says, as they were alarmed by escalating acts of vandalism and hate, such as graffiti and a pig's head that was left on the mosque's steps.

The renovations and security upgrades were completed in March 2021.

At least two volunteers now monitor security cameras at all times, to watch over worshippers as they pray.

Khabar thinks the building is more secure.

There have been cosmetic, yet meaningful, changes too.

Sections of the old green carpet that were stained with blood had already been removed after the shooting, but now it's been fully replaced. The new carpet is red.

After the shooting, mosque leaders had left bullet holes in the walls — scars on the building that mirrored the scars left on the community itself.

Those scarred walls have since been plastered over and repainted a gleaming white. The brightness is intentional.

The idea is "to turn the page and have a sign of peace when you enter the mosque,'' said Labidi.

"Our objective is to forget the tragedy, and what happened here at the time."

'You feel you're targeted'

But in the world outside the mosque's walls — despite the messages of solidarity and sympathy — the two men say it can be hard to forget that their community was, and is still, the target of hate and discrimination.

Khabar says his life is not like before — beyond running his barbershop, he's also meeting with politicians, advocating for gun control and denouncing Islamophobia.

"You feel like you're targeted by laws … that don't help you forget what happened at the mosque," Khabar said.

Labidi points to Quebec's secularism law, known as Bill 21, that bans the wearing of religious symbols including the hijab, for public employees in "positions of authority" including teachers.

''We are all affected by this law because … there is discrimination in this law, and it should not be allowed in this society," he said.

Since the bill was adopted, Labidi says at least a dozen families have left Quebec. He says even for those whose jobs were not directly affected, the law has eroded their sense of belonging.

Quebec Muslims 'disillusioned'

This sentiment is backed up by research published last year in the journal Canadian Ethnic Studies, by researchers Geneviève Mercier-Dalphond and Denise Helly, which found that the shooting, the rise of right-wing extremist groups and laws such as Bill 21 have all had an impact on the well-being of Muslims in Canada.

However, the study found Montreal and Quebec City respondents were "more concerned with institutionalised Islamophobia in the form of laws, namely Bill 21."

The study found Quebec respondents were "disillusioned" that the shooting was not the turning point they hoped.

Quebec Premier François Legault has repeatedly defended the bill, saying it's neither aimed at Muslims nor motivated by racism.

He said recently he will attend the ceremony marking the anniversary of the shooting on Saturday.

'A message of hope'

Despite the disillusionment he sees among Muslim Quebecers, Labidi says he still feels the support of the broader community.

"There are a lot of people whose views changed," after the shooting, he said. "Everyone in the community still sees it, five years later."

He wants this year's commemoration to be "a message of hope" that Quebecers can be stronger together, and that the Muslim community is "a part of this society."

Even though he still has pain when he stands for too long, and replays the shooting in his mind, Khabar has hope too.

He hopes that his son, who is now five, will grow up feeling safe.

"I'm an eternal optimist," he said, "I think things will change."