Mapping the Wabanaki canoe routes of yesteryear

Since people have lived in New Brunswick, there have been highways, though not all were created equal.

In 2015, the provincial government closed the neglected Jemseg Bridge, leaving a large section of the former Trans-Canada Highway still standing — abandoned and inaccessible.

Part of a so-called "modern highway," the route has decayed past the point of use just a few decades after it was built.

But underneath it runs another highway, thousands of years old, and still in working condition.

The Jemseg River, along with hundreds of other rivers, creeks, and streams make up the highways used for centuries by First Nations communities for trade and travel using birch-bark canoes.

\

Some of these routes are well-recognized today, their winding routes shared though the oral history of several First Nation communities. Others were thoroughly recorded by famed New Brunswick cartographer and historian William Francis Ganong.

Some are less known, and some may be lost to history, but researchers are working to map those possible routes using a combination of computer software and linguistics study.

"One of the things I was interested in looking at was the use of smaller, or more ephemeral routes, that would have been only available during some times of year," said Chris Shaw, a graduate student at the University of New Brunswick. "Such as smaller headwaters, or smaller rivers between the major watersheds of the St. Croix and the St. John that may have only been usable when it was high water or in the freshet flooding season in the spring."

By using annual recorded water levels and cross-referencing them with known archeological sites, Shaw is mapping where people of the Wabanaki Confederacy could have travelled by birch bark canoe during different times of the year.

The Wabanaki are made up of the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Abenaki nations stretching from Maine, across the Maritimes, and parts of Quebec.

"Maps 100 years ago, or even more recently than that, aren't as effective as computers and geographical information systems at showing how landscapes can change over time or even over short time scales," Shaw said.

"So what I've done is use computer-modelling tools that look at how canoe travel routes and times would have changed seasonally based on water levels and the velocity of the waters."

"Those environmental changes may have affected the ways prehistoric ancestral Wabanaki people would have moved through the landscape, the routes they would have selected, and how long it would take to move to significant places such as archeological sites in the interior to coastlines."

Shaw has also been able to map what travel times would be like along those routes by averaging water flow during different seasons.

A different approach

Instead of looking at the strict data provided by computer modelling, another researcher at UNB is trying to map ancient canoe highways by studying the language of the people who travelled them.

Mallory Moran, a PhD candidate in the department of anthropology at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, studies First Nations travel routes out of UNB by matching names and nomenclature.

"We are still trying to figure out where all the routes went," Moran said. "That's one of the questions we are still trying to bring into focus.

"I am looking at it from a linguistic perspective. So I study the place names of this region to try and understand the broader cultural landscape of New Brunswick."

"They are First Nation names, so they are very ancient," Moran said. "I'm able to work with early European maps to note where all the names are on the landscape and develop a map of place names."

Moran said discovering the ancient named portage routes, where people would carry their canoes across land to access different waterways, are important landmarks that help connect the dots of centuries-old routes.

"Many of these routes were part of a seasonal cycle. And we can tell by the names of these routes that they were used for the hunting of specific animals, or to hunt specific fish, and so it gives us an idea of why people were moving."

Moran points to the First Nations names of many New Brunswick rivers, specifically in the northern and eastern sections of the province, as examples of language describing seasonal purposes, and is working to map out similar, less known, possible routes in the same manner.

This summer Moran is organizing travel alongside different First Nations communities to examine many of these pathways in person.

Sharing the story

Despite being perhaps thousands of years old, many of the ancient routes are still intact and can be travelled. And although Fiberglas and plastic are what canoes are made of today, they are not the first choice for the descendants of those who first travelled these waterways.

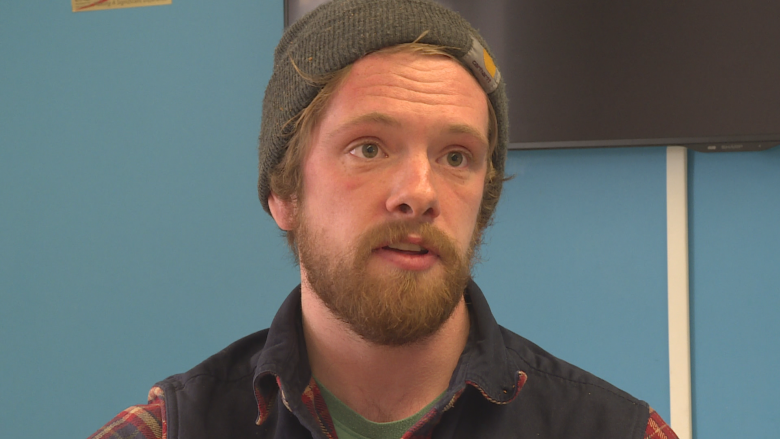

"I've built three of these canoes," Shane Perley-Dutcher said.

The Tobique First Nation resident has worked extensively with birch bark to build canoes the way his ancestors did in centuries past.

"And it basically changed me," Perley-Dutcher said. "Working with that material opened up a whole window into my culture."

An artist and a band councillor, he said the routes wind through the history of his people, not just during contact with the French and Europeans but as far back as 12,000 years ago.

"The rivers were our highways, and those portage routes were our main travel areas so that we could acquire things from other nations that we could use in our own communities."

"We were constantly going back and forth," Perley-Dutcher said. "So it's important to know those things because it really explains how we built our society."

As well as being used for trade and hunting, Perely-Dutcher said, the rivers were used extensively for keeping strong relations with neighbouring nations and establishing and maintaining diplomacy between communities across great distances.

Studying and researching these routes, even as they open up again from winter's ice, is a start to reconnecting, and acknowledging the past he said.

"We have a history of not talking about our history, the real history of New Brunswick and of Canada. And I think that's starting to change."