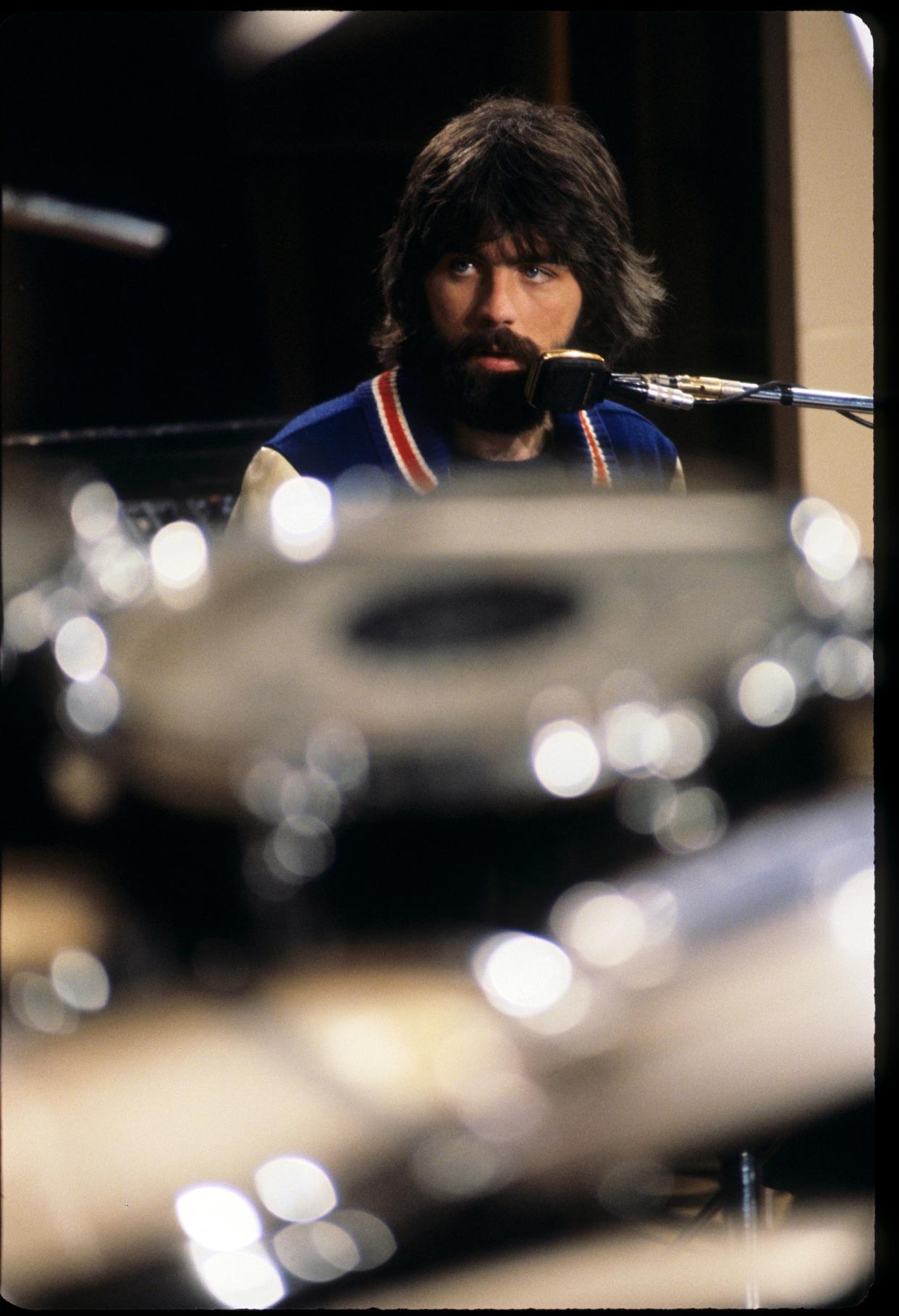

Michael McDonald, Silken-Voiced Yacht-Rock Icon, Talks About Writing His Life Story With Paul Reiser (Yes, That Paul Reiser)

ABC Photo Archives/Getty Images

Everybody is always a little late to a Zoom interview, so I’m shocked when I log on five minutes early to make sure everything is kosher and see Michael McDonald sitting there patiently, white beard matching his slicked-back head of white hair. He’s 72 and wears it well. He sounds good, too—like it hasn’t been decades since he sang “Takin’ It to the Streets” with the Doobie Brothers, or the floating-down-from-a-cloud backing vocals on Steely Dan’s “Peg.” Once you hear his voice, it’s in your head forever. To steal one from an old Saturday Night Live sketch, it’s like buttah. Blue-eyed soul that melts your inner core, undoubtedly the soundtrack to the conception of thousands of babies over the years. You have to be confident to have a voice like that, but McDonald is polite and soft-spoken when I thank him for dialling in before I did.

“I always figure it’s best to start early,” he says, “because I never know how to figure out these things, getting on Zoom and all that.”

McDonald is here to talk about his new memoir, What a Fool Believes, named for the 1979 Doobie Brothers hit. The book, which he co-wrote with Paul Reiser—yes, the Paul Reiser, more on this in a moment—isn’t your typical Yeah, we trashed a few hotel rooms and banged some groupies, but then things changed… kind of rock-star autobiography. It’s deeper than that, more honest, light on the bravado. It begins way back when, long before the Doobies and Steely Dan, with McDonald recounting his early days as a rock and soul-obsessed kid from the St. Louis suburbs. It was the early 1960s; regional garage-band scenes were popping up all over the country. Guys who’d watched how Brits like the Beatles and the Stones made girls scream and cry and decided they wanted to do that. Usually that was their first reference: John and Paul and Mick and Keef, not the blues and soul the Brits were borrowing from. But McDonald was a little different. He was an explorer. He got so deep into music that there was no getting out, and that’s what we were starting to talk about when his coauthor logged on.

Paul Reiser: How are you doing, Michael?

Michael McDonald: Good. I was doing better until I saw the full screen. I’m like the poster boy for liver spots.

Reiser: No. You look remarkably healthy.

GQ: Yeah, your hair is perfect. So tell me how you guys met.

Reiser: I’ve got a picture of Mike with my kids, so it's got to be 15 years maybe. Mike was performing at this private event that I was invited to and I walked in and went, Holy shit. Michael McDonald is the entertainment? That's pretty cool. And then I went over and said hello and told him what a big fan I was. Then, in a jolt of moxie that I don't always have, I told him I live 40 feet from here, and I have a music studio with two pianos just in case something like this ever occurred. You want to come over and play? And, God bless him…

McDonald: …I said, yeah, sure. So we sat and played and that was where it all started. I was very familiar with Paul's work and I was pleasantly surprised that he was a fan of Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers, and so we hit it off right away just talking about music. Then we literally walked across the driveway to his house, and there are these two grand pianos. We were sitting there playing our favorite Beatles songs and our discussions were fun because I don't normally get to talk to people about things like all the great bridges from Beatles songs. There was an era of Beatles songs, like from the Something New album to Beatles VI, where all their songs had these great bridges, and I was always amazed by that. So we were sitting around picking out the bridges from different Beatles songs and just really having fun the way that only two people who are that neurotic about Beatles songs can have, I guess.

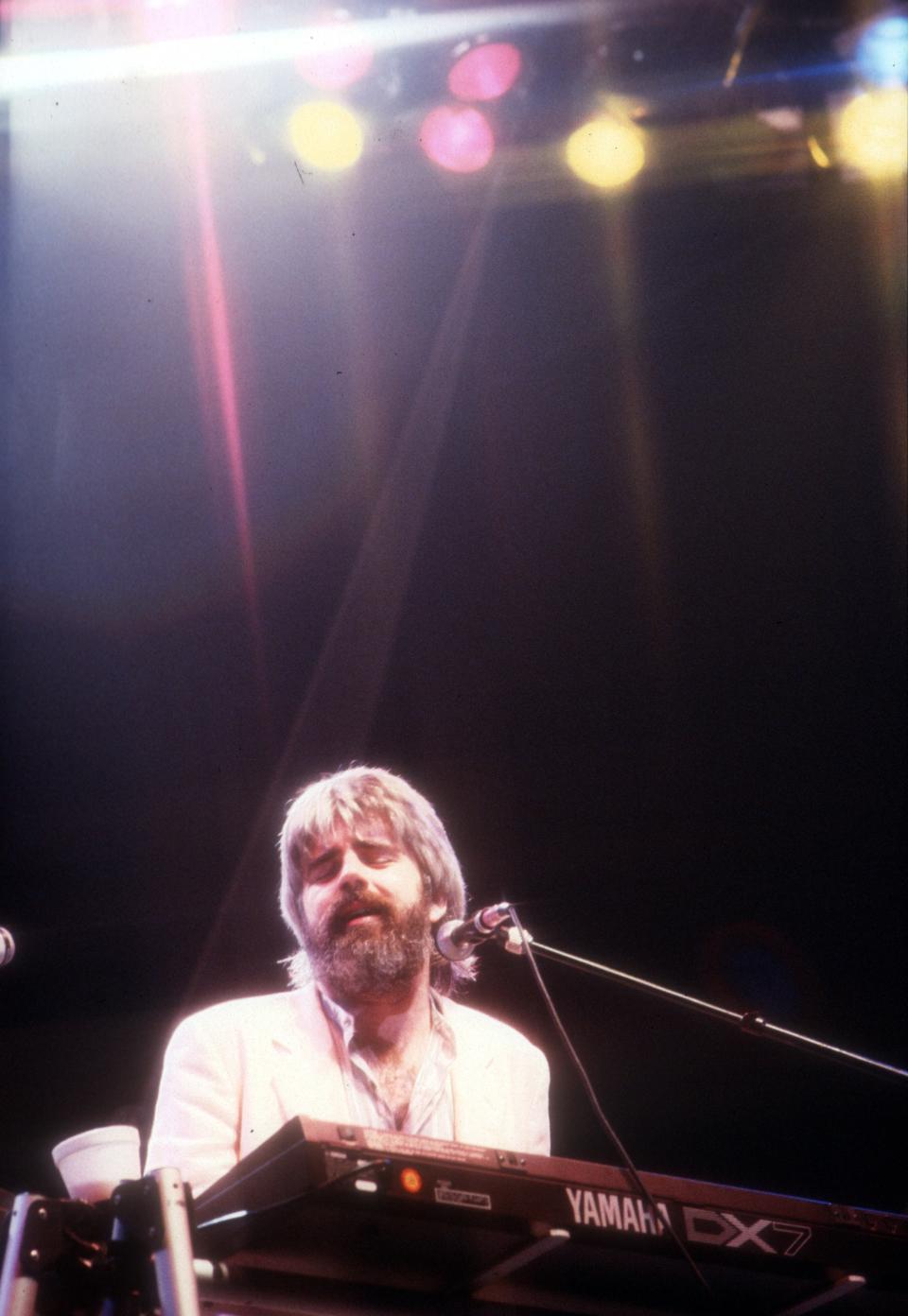

Photo of Michael McDonald

I’ll be honest and say maybe eight times out of ten, I hate music memoirs because they feel like they’re just there to sort of boost the faded legacy of a musician. But you guys did such a great job with this. One thing that stood out is how honest you were, Michael, about what you say was a “subconscious resentment towards women” when you were younger. That struck me, because a lot of male musicians from your era tend to revel in the macho antics of their younger years. What made you want to discuss that?

McDonald: I don't know what I thought it would explain, to be honest with you, but I thought it was somehow a bit of insight. We threw a lot of stuff against the wall. Paul interviewed me for a month before we even did this and we then transcribed all these interviews. So he's worked a lot harder on this book than I have, but we talked about the certain things that should stay and shouldn't stay and that was one of 'em. And I think we both felt it was important. It was some kind of insight into all that would take place later in my life, it has been an issue for me in relationships throughout my growing up period and my adulthood. So I didn't have to dig too deep. It was not like a shrink session.

Reiser: Mike has done so much exploration and understanding of his life, which is why it's great that he decided to do this book now as opposed to 10 or 20 years ago. I think there's a vantage point that he has of who he is and how he got here, which is really what the book is about. But if there's one thing I can say about Michael McDonald it’s that he's remarkably honest and humble, but also forthcoming. He owns every piece of his life that he can. So it didn't take a lot of excavation. It was two of us talking on Zoom and he was just sharing this stuff. I was a big fan of Mike’s, and the reason I first said “You should write a book” to him was because I really wanted to read it. I didn’t know his story. I love his music, but I really know very little about him, and now I do.

Paul, people know you from your standup career, from Mad About You, or as the author of a few best-selling books of your own, but two of my favorite things you’ve done as an actor are Barry Levinson’s 1982 film Diner and the Amazon series Red Oaks. And a thing about those projects was you were interpreting another person’s nostalgia as an actor. Here, you’re doing something similar by taking Michael’s memories and shaping them into a story. How did you approach doing this project?

Reiser: We approached it thinking, This might be the dumbest idea in the world or it might be fun. I would periodically ask Mike questions, about Steely Dan or the Doobies and how he went from one thing to the other. And at one point I jokingly said You should write a book, so I didn’t have to ask you all the questions. He said people had mentioned that to him, but he didn’t know if there was a story there or how to do it. And that's when I said, well, let's just do this.

I had no approach and I had no tone that I was going for; I was just asking genuine questions that I was curious about, and Mike was sharing everything that came up. A lot of the stories ended up not being used because they weren’t really about Mike. He’d go, I'll tell you a funny thing that happened to my friend. I’d say, Well, that's great. That goes in his book. That's not your book. This is Mike's story. I didn't write it. These are all verbatim Mike's stories. Mike's laying himself bare, and all I did was sometimes pull it out of him a little more or ask him to go deeper or explain and then just sort of help organize the material. But it's not a book I wrote— it's just Mike's book that I was honored to and flattered that he let me help him walk through it.

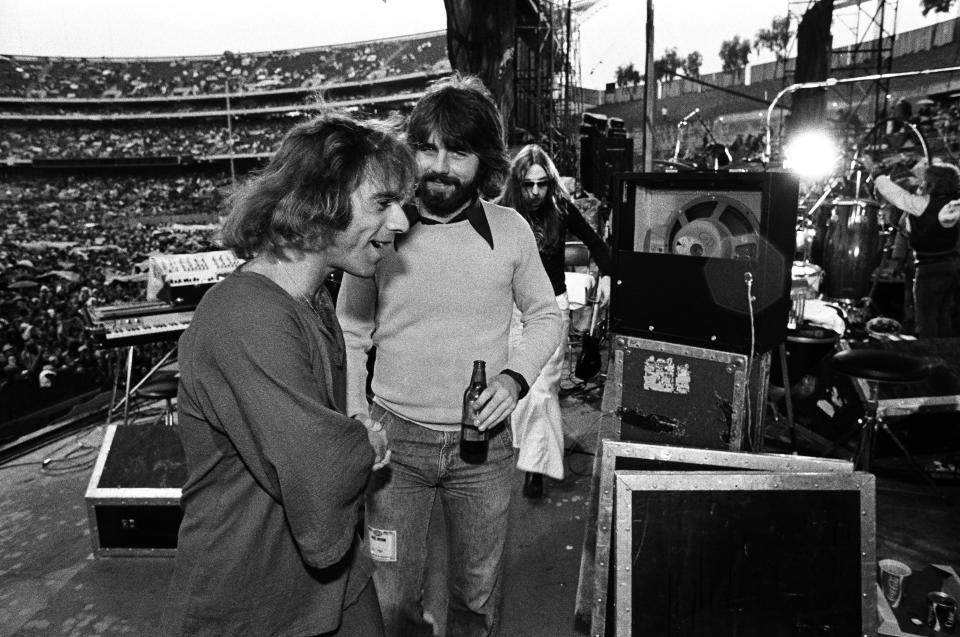

Peter Frampton And Michael McDonald

The book shows Michael’s rise from local garage bands playing parties to a band like the Del-Rays who put out a single on Stax, then session work, and eventually bands like the Doobies and later the solo success. It made me think of the old-school rock journeyman thing other guys of your generation like Bob Seger or Glenn Frey did before they found success. I haven’t seen many books that really focus on that part of a career as much as you did. Why was it so important to focus so much on that era?

McDonald: I think it was what Paul was saying, how a lot of the times I would say, Oh, I think this is a great story to tell, and I was fortunate to have Paul, with his ability as a writer, to look at something and go, Here's your story right here. All this other stuff, you're repeating yourself because you think this is important. And you keep repeating it like you think that reader is an idiot. It was really in the organization and editing that we did along the way that the story came together. That was the expertise I was able to tap into with Paul.

Reiser: One of the reasons I think this book is resonating with people and one of the reasons I think we're both proud of it is it works on a couple of levels. There are not a lot of artists who have the scale and the scope of Mike's career, from playing church basements in St. Louis to rock festivals and then to all his success to arenas and then his solo career. So there is a story there, and that, as the French would say, dayenu—that would've been enough just to have this chronology of rock and roll and rock and the L.A. music scene in the seventies that nobody knows better than Mike McDonald. But along the way, out of excavating these stories is this arc of Mike the person and his very unique, distinctive childhood and musical influences. His dad and his family, the St. Louis music scene, his journey through alcohol and drugs; Mike finding himself and finding Amy and finding his center in light. So they kind of work in dovetail together. You're getting all the nuts and bolts. I think anybody who wants a really accurate and detailed telling of pop history from the ‘70s to now, it's in this book. But what really carries it is this guy and how his personality really comes out. I think that's a testament to how honest and open Mike was with sharing everything.

McDonald: I think the message is a universal one; it’s about the randomness of life and how miraculously sometimes we just skirt the disaster right and left. You don't realize that life is really not made up of our choices; it’s made up of random events and the amount of providence that we're blessed with along the way. And many times it flies in the face of our own actions.

Reiser: If you trace Mike's trajectory, it's like, okay, the Doobie Brothers came because of Steely Dan, and Steely Dan came because of how a guy that he played with once called him a year later and said, Hey, can you come down right now and try out? And Mike just jumped in his Pinto and had no time to prepare, and after five hours of what became a rehearsal period, Mike was never told he was in the band. Okay, well now you're in Steely Dan. So to me, that checks both boxes. It's like that's how rock history happens. The guy says, can you come down and put your Wurlitzer in the Pinto and get over here? The next thing you know, you're in Europe backing up Steely Dan, and then you're back in Glendale playing a bar to 12 people. And then you get another call, and now you're in the Doobie Brothers. Is that how it happens? Yeah, that's how it happens. There was no curriculum that you could sign on to join the Doobies: You got a phone call and then because you have Mike's skills and unique talent, you’re in.

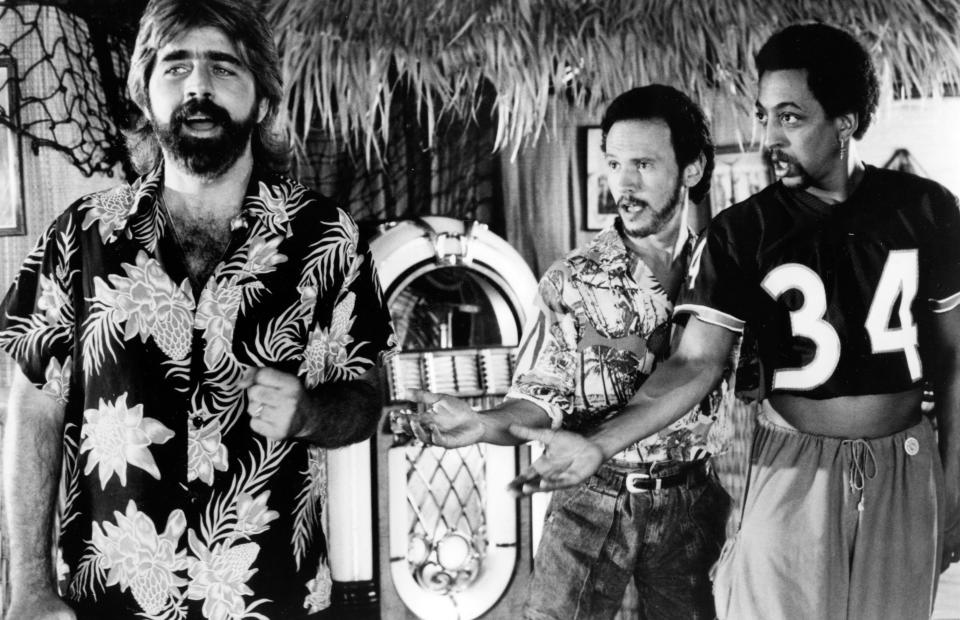

Gregory Hines Music Video

Something that might get overlooked is how much comedy and music have in common. The endless touring, the small clubs, the hecklers. Were there times where you guys were discussing your paths and you realized your stories have a lot in common?

Reiser: Yeah. It was like we had hecklers and we both had a couple of stories about terrible audiences we were sharing, and out of that came some of the stories in the book about opening for Cher in France, then hearing a whistle and going, I think they like us. No, they're telling us to get the fuck off the stage. So we all have our nightmare stories and to me those are the most fun parts. And as a comedian, I remember whenever there was a horrendous night—and there were nights that were just terrible—in the back of your head, you're thinking This will be a good story. It's a terrible night, but this will be a funny story later.

McDonald: Microcosm of life right there. I think comedians have it worse, though, because they have to have the audience’s attention. Musicians can get away with it because people largely ignore them in lounges and places like that.

And people tend to be drunk at comedy shows; they’re usually on more drugs at concerts. Paul, I know you’ve talked in the past about how comedy records were so important to you growing up, but you were also a musician, so you appreciate both forms. Michael, were there any comedy records you liked back in the day?

McDonald: I remember one record we used to get stoned and listen to. It wasn't a comedy record, but it was Jack Webb reciting poetry and it was so great. The cover was him, those little thin ties, the real stern look on his face, just like Dragnet. And pretty much his delivery of the poems was not too different from the way his dialogue was on TV.

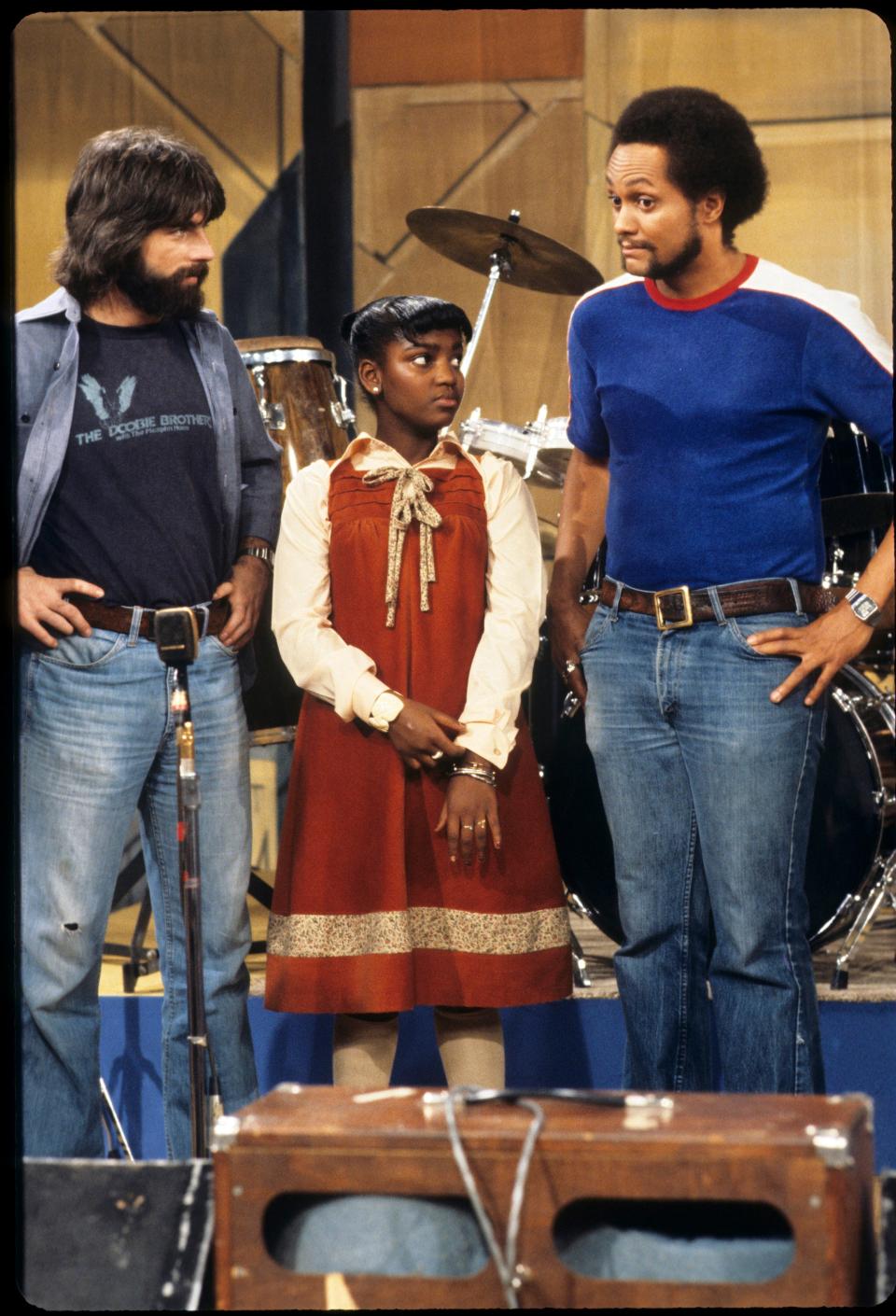

DANIELLE SPENCER WITH MICHAEL MCDONALD (L) AND TIRAN PORTER OF THE DOOBIE BROTHERS

Was there a lot of overlap with comedy in your early days? Albert Brooks and Richard Pryor and George Carlin were playing in some of the same clubs. Maybe Cheech and Chong?

McDonald: We didn't play with those guys, but we went to their club. We were kind of scheduled to do the second Up in Smoke movie with them. They had a club up in Vancouver where they would try out new material, and they were both loaded that night, and it ended up being one of those nights that went on and on. It was fun to watch. I remember when we did Saturday Night Live once, we went to a party after at this warehouse in Manhattan, maybe Lower Manhattan, where the guys rented the place out, always had a fully-stocked bar, and after every episode, they would go and hang there.

The Blues Bar? Aykroyd and Belushi’s place?

McDonald: Yeah. That was a riot. Seeing comics after the show, that can be a really interesting character study, especially if there's a little alcohol involved. It gets pretty crazy. I remember Bill Murray trying to moon us while we were leaving. He fell down and started rolling down the street.

Did you open for a lot of bands, Paul?

Reiser: Not a lot. My first real gig was at the Bottom Line where I opened for Buddy Rich—which was not a particularly salient pairing, but it was fine. But I did a couple of short tours with the Pointer Sisters, and opened for Melissa Manchester. That was a more civil crowd. I can't remember too many more than that. But yeah, you open for bands, a local band sometimes. It was usually tough. It's like you just couldn't wait to get the check and get out of there.

Since we talked about early bands, Paul, is there an old garage band of yours that will have an old single dug up and reissued at some point?

Reiser: Oh, I hope not. I had a band—the Upper Deck was the name. We were very big in my building, and we were 12, 13, 14. And then about five years ago, we decided to all get together again. Everybody came out to L.A. and we played in the room where Mike and I first played, and I was very tickled to see that in 50 years time we had gotten no better and actually got a little bit worse. We played “Gloria,” and a couple of Traffic songs. We were just really bad. Luckily, there were no recordings made.

Michael, you worked with Steely Dan’s Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, two of the most famously obsessive musicians of the modern era. How does working with Paul Reiser compare? Who cracks the whip more?

McDonald: [laughing] Paul’s much nicer to me.

Originally Appeared on GQ