Missouri veteran facing June execution reflects on murder case, family and faith

David Hosier, who once walked the halls of the Pentagon and fought fires in Jefferson City, is “not looking forward” to June 11.

At 6 p.m. that Tuesday, he is scheduled to die from a lethal dose of pentobarbital while strapped to a gurney at a prison in eastern Missouri.

Hosier is as he puts it, “The sum of the parts that I am and that’s it. I’m not an angel, I know that. I’m human, I make mistakes, we all make mistakes.”

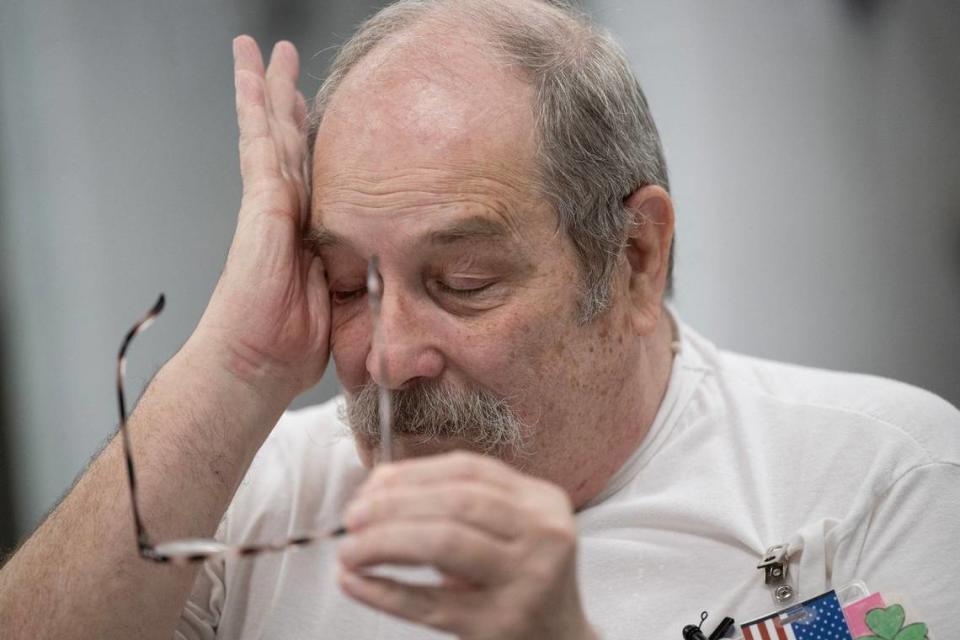

The 69-year-old has been incarcerated at Potosi Correctional Center, about 70 miles south of St. Louis. He spoke to The Star Tuesday in one of the prison’s visiting rooms featuring a row of phone booths and a mural of a bright blue pond with two swans painted across the cinder block walls.

Seated in a wheelchair and gripping a cane, Hosier said he was feeling much better. He had been released from a hospital last Sunday after being admitted for apparent heart failure.

At times while talking, Hosier is matter-of-fact, but then turns emotional. He can be quick to blame but easily expresses empathy, too. In some moments, he’s self-deprecating; in others, unyielding in his beliefs.

He will be the second person put to death by the state this year. Last month, Brian Dorsey, 52, was executed.

Hosier was sentenced to death in 2013 for the murder of Angela Gilpin, 45. She and her husband Rodney Gilpin, 61, were found dead Sept. 28, 2009, in the hallway of her Jefferson City apartment building.

Angela Gilpin and Hosier had been in a relationship before she ended up reconciling with her husband.

Prosecutors presented him as a scorned ex-lover and he was convicted on circumstantial evidence, including an application for a protective order in which Angela Gilpin alleged he had been stalking her and that she was afraid of him. A neighbor told police that Hosier had once said if he could not have Angela Gilpin, no one could, court documents said.

Hosier was arrested in Oklahoma hours after the bodies were discovered. He was taken into custody after a brief chase and was found with 400 rounds of ammunition and 15 firearms, court records said.

Police also found an incriminating note that stated in part, “If you are going with someone do not lie to them ... Be honest with them and tell them if there is something wrong. If you do not this could happen to YOU!! ... they can go off the deap [sic] end!!” While prosecutors could not pin him at the scene of the murders, he also did not have an alibi.

Hosier insists he did not kill the Gilpins. There were no witnesses and no DNA evidence linking him to the double homicide. He rejected a plea deal taking capital punishment off the table.

“You cannot show remorse for something you did not do,” he said.

But most of his advocates are not vigorously promoting his narrative even as they fight to save his life.

Instead they point to other mitigating factors: Childhood trauma from the violent death of his father, failures of the public defender system and the moral question surrounding the death penalty itself.

‘I lost my best friend’

Hosier grew up in a Logansport, Indiana, in a neighborhood situated a half block from a river. There were always other kids to play with and he often fished and hunted with them.

The youngest of three, his mom was a nurse and his dad was an Indiana state trooper. He was also close with his paternal grandfather, who was a minister.

Hosier was 16 when his father was fatally shot while apprehending a murder suspect. As a teen, he had thought about the possibility that his dad’s job meant one day he would not return home.

“It’s nothing you can really prepare for but at least I had, between my dad and my grandfather, prepared for something of that nature,” Hosier said. “It’s just hard to describe.”

“I lost my best friend. What can I say? We did a lot of things together, we’d hunt, we’d fish, we’d pal around.”

His father’s death was hard on the family and Hosier was sent to military school. He served six years in the Navy, which he called “an adventure of a lifetime.”

While he was in the service, he said he spent time at the Pentagon and also got married.

That ended in divorce and after he was discharged, he moved back to Indiana.

In 1979, he visited his oldest sister in Jefferson City and ended up staying in Missouri. He got a job with the fire department and was married for a second time. They had a son and a daughter.

Between his job and part-time gigs, including managing liquor stores, Hosier said he “missed family get togethers, birthdays, holidays.” It took a toll on his marriage and he got divorced in 1987. He wound up back in Indiana where he farmed for about two decades.

In 2006, he came back to Missouri for his son’s wedding and again, stayed.

“I wished I never had,” he said.

‘Nobody deserves anything like that’

Hosier got a job and an apartment in Jefferson City, and frequented a bar owned by a guy he knew from the fire department.

He didn’t care for drinking but said, “I like to throw darts and I like to shoot pool and I like to listen to country music and dance.”

He met the Gilpins at the bar, where they often played pool. They became friends. “One thing led to another,” he said, with Angela Gilpin.

“It takes two to have an affair,” he also said.

Down the line, she decided to go back to her husband.

“The fact that they were killed, nobody deserves anything like that,” Hosier said.

Hosier points fingers at many people for where he’s ended up, including the police, prosecutor, judge and his own attorneys. He refers to the public defenders who represented him as “public pretenders.”

According to appeals, trial attorneys with the Missouri State Public Defender’s office ineffectively questioned two potential jurors, failed to hire an expert to contest ballistics evidence, did not properly object during closing arguments, failed to object to victim impact evidence and failed to call a medical expert to testify about Hosier’s mental health during the penalty phase.

Federal public defenders from the Kansas City office also missed a key filing date on an appeal, he said.

“We all make mistakes, but when it’s a person’s life on the line, whether you’re being paid by the same people that want to execute you or not, you give it 100%,” Hosier said. “And I’m disappointed that they missed it, but I can’t fault them because we’re all human. Humans make mistakes. So consequently, I’m sitting here with an execution date, waiting to die.”

He also acknowledged that public defenders often have burdensome caseloads and fewer resources than prosecutor’s offices.

‘Say my farewells’

The Missouri Supreme Court handed down Hosier’s execution date on Valentine’s Day. Prison officials broke the news and he packed up the belongings in his cell to be moved to solitary confinement, where those with an execution date live out their days.

“They at least let me say goodbye to all the guys in our wing,” he said, choking up. “I got to say my farewells. They didn’t have to, but they at least let me and that’s how I learned about my execution date.”

Hosier did not elaborate on what prison had been like, other than to say, “it’s not any place you want to be.”

In solitary, he’s confined to a 7 by 15 foot cell where he spends 24 hours a day, except for legal and media visits or medical appointments.

He connected with a spiritual advisor, the Rev. Jeff Hood, who has helped six men face their execution dates in the past 18 months.

A 2022 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court granted spiritual advisors the right to accompany prisoners in the execution chamber.

“We talk a lot about the Bible and different things,” Hosier said. “We talk, just trying to get prepared for the state wanting to murder you.”

They speak two or three times a day, sometimes.

“I have come to love David,” Hood said.

His job, Hood said, is to get Hosier to a space where he can open up and feels heard and a place of believing that God loves him.

‘What God intended’

If Hosier had been asked about the death penalty after his father was killed, he may have said it was appropriate. But his view has changed over the years and after being entangled in the system, he’s firm that it should not be used.

“I can’t see by any justification, the death penalty as being anything but cruel and inhumane,” he said.

“The state says it’s illegal for us to kill somebody, but they can sanction a murder and it’s a-OK, no big deal.”

Michelle Smith, co-director of Missourians to Abolish the Death Penalty, said capital punishment was an arbitrary tool that does not bring the dead back and does not deter crime.

“It does not solve anything,” Smith said, adding that the organization supports life without parole for Hosier. “We shouldn’t be killing people.”

Rodney Gilpin’s sister Raylene Vaughan said Hosier “should be held accountable for what he did.” While she isn’t opposed to clemency, meaning life without the possibility of parole, she said she also feels like he should have to give his life.

Attempts to reach other family members of the Gilpins weren’t successful.

Hosier’s legal team will soon submit a clemency application to Gov. Mike Parson’s office.

Hosier said he hopes the governor takes a close look at the case. If Parson decides “nothing is wrong” and proceeds with the execution, “that’s on him,” Hosier said.

Parson will one day meet his maker at the gates, Hosier said, and “I’ll shake his hand and I’ll still call him brethren.”

Parson has denied clemency in all 10 of the death penalty cases that have come across his desk. Hosier said he is aware that everyone who has gone before him is “six feet underground.”

As June nears, Hosier reflects on his life: the love and admiration he had for his dad, his close relationship with his sister, Barbara Merrill, who supports his innocence claims, and his kids, who he is not in contact with.

“I do love all my kids,” he said. “No matter what, they’re my kids, whether they want to claim me as their father or not. I’m sorry, I’m still your dad.”

Hosier has also relied on God.

“My faith’s been with me all my life. It’s basically what keeps me going in here and that’s one thing no one can take,” he said.

He also said he remains saddened by the deaths of Angela and Rodney Gilpin, and the pain their families have suffered.

“If my being executed makes you feel any better, then I guess maybe that’s what God intended,” he said.