Moncton airport adopts international program to recognize people with hidden disabilities

A program that helps people with hidden disabilities at airports, that has gained international traction in recent years, is coming to Moncton.

"It really coincides with our commitment to providing an exceptional passenger experience," said Courtney Burns, president and CEO of the Greater Moncton Roméo LeBlanc International Airport Authority.

The Hidden Disabilities Sunflower program is designed for people who have what are sometimes called invisible disabilities.

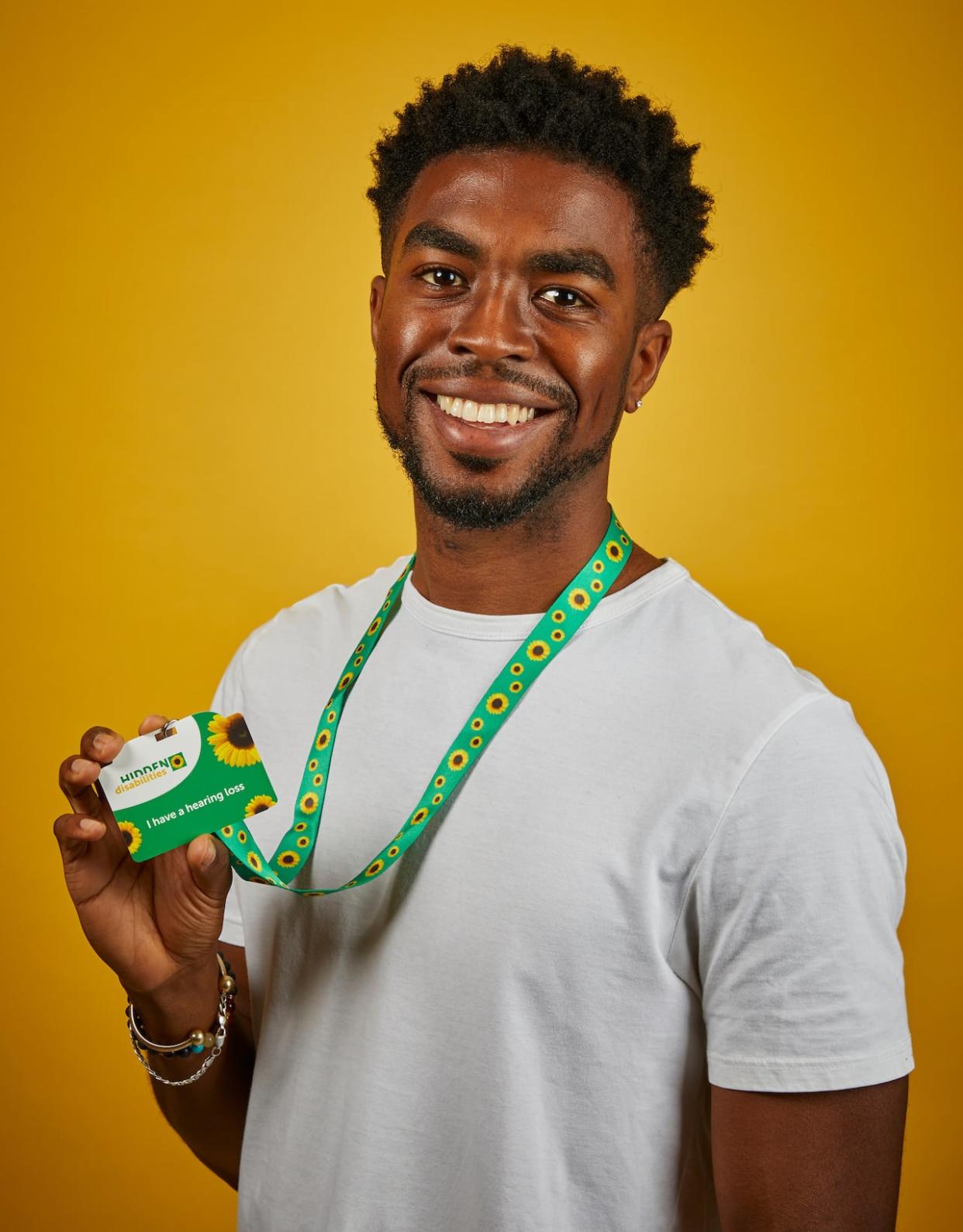

A sunflower symbol displayed on a green lanyard, which is available for free at the airport, allows the wearer to voluntarily show that they have a disability and may need extra time, patience or help.

Paul White said six airports in Canada, in addition to Moncton, have the sunflower program — Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, Ottawa, Comox Valley, B.C., and Regina. (CBC Graphics)

Burns said the lanyard could be used by anyone with a hidden disability, such as autism, multiple sclerosis, COPD, dementia and hearing loss.

The Hidden Disabilities Sunflower organization lists more than 900 conditions or chronic illnesses that the sunflower represents on their website.

Paul White, the organization's CEO, who is based in London, England, said the idea started eight years ago, when London's Gatwick Airport recognized it was easy to identify those with visible disabilities who might need help, but they couldn't see those with invisible challenges who might require extra assistance.

Paul White, CEO of Hidden Disabilities Sunflower, said the sunflower program began in the United Kingdom and spread from there. (Submitted by Paul White)

White said the program was an instant success and continued to spread, including to places outside the United Kingdom, even more so after COVID-19 restrictions lifted and people started travelling again.

White said the symbol for someone with a disability has long been a person in a wheelchair, but he noted that only a small percentage of disabled people actually require such a device.

"That symbol can really create a lot of confusion for people because a disabled person walks out of the disabled toilet and people expect to see a person in a wheelchair and often questions are asked to that person," said White.

"That's really, I think, why the sunflower has kind of been so successful, because it's kind of the symbol that captures all conditions."

White said when a business brings in the sunflower lanyards, the program asks that they be available at no cost so that people aren't being financially penalized for their disability. Then, the program trains businesses and staff about the meaning of the sunflower and how to support someone wearing it.

In addition to the Moncton airport, White said six other airports in Canada have started using the sunflower program — Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, Ottawa, Comox Valley and Regina — along with the ariline Air Canada.

White said the symbol for someone with a disability has long been a person in a wheelchair, but since only a small percentage of disabled people actually require a wheelchair, he said it can sometimes cause confusion. (Getty Images/EyeEm)

In an emailed statement, Fredericton International Airport spokesperson Kate O'Rourke said while the sunflower program isn't offered at the airport, they work closely with "community groups to ensure we're meeting the needs of all our passengers with disabilities, whether invisible or visible."

A spokesperson for the Saint John Airport, Lori Carle, said in an email the program is on her list and to "stay tuned."

Shelley Petit, chairperson of the New Brunswick Coalition of Persons with Disabilities, said the program's implementation at the Moncton airport will make a difference for so many people, even though it won;t her her, personally. Petit said she won't be able to fly again because of her disability, multiple chemical sensitivity.

Shelley Petit of the New Brunswick Coalition of Persons with Disabilities said the lanyard will make a huge difference for thoe with an invisible disability. (Submitted by Shelley Petit)

She said she's been pushing for the program to be brought into Canadian airports for about six years, ever since she read an article about its use at an airport in the United States.

Petit said 15 years ago, she flew with her young daughter, who has autism. By the time they arrived in Alberta, she said she needed a week and a half just to recover from the challenging journey.

"That lanyard could have made that trip so much better," she said.

Petit said the extra assistance one receives could be as simple as putting a bag in the overhead bin or reading a menu. Whatever it is, she said having the lanyard will take away the extra burden of someone having to explain their disability and why they need help.

"We hate to have to explain over and over and over again," she said. "So then what do we do? We don't say anything [and] we suffer the consequences. And then it just exacerbates our condition."