For most of history, we haven't had abortion laws, and we don't need them now

This column is an opinion by Ainsley Hawthorn, a writer and cultural historian in St. John's. For more information about CBC's Opinion section, please see the FAQ.

According to a new study from Angus Reid, three out of five Canadians believe Canada needs a law to guarantee access to abortion.

Canada is one of the few countries in the world without any abortion law on the books. Instead, abortion is treated like other medical procedures and regulated by provincial and territorial health authorities.

That may seem strange when we're so used to framing the abortion debate as a legal issue. But abortion hasn't always been considered a matter for the courts, and it doesn't need to be today.

Not persons but property

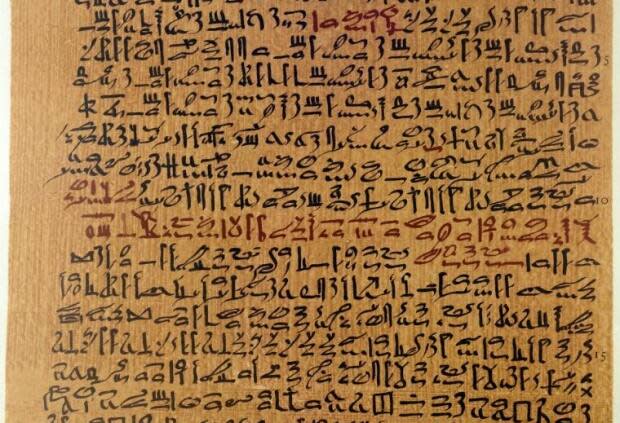

Abortions were part of medical care in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, Greece, and Rome.

Fetuses rarely come up in ancient legal codes, but when they do, they're treated like property, not persons.

In the Code of Hammurabi, written in Mesopotamia between 1792 and 1750 BC, and in Exodus, one of the books of the Hebrew Torah, if a man strikes a woman and she miscarries, he has to pay a fine. If she dies, on the other hand, he must forfeit a life for a life.

The woman and the fetus aren't in the same legal category, and the loss of one doesn't trigger the same consequences as the loss of the other.

This scenario is about traumatic miscarriage, where a third party has caused a pregnancy to end through violence or negligence. What about voluntary abortion, where a woman chooses to end her own pregnancy?

A handful of laws in states like Assyria and Rome made voluntary abortion a crime, not because the woman was murdering an unborn child but because she was destroying something that didn't belong to her. Under a deeply patriarchal system, the fetus was seen as the property of the man who fathered it.

Still, there's a possibility that paternal rights were only a cover for shoring up a shrinking population.

Caesar Augustus saw Rome's low birth rate as a threat to the stability of the state and publicly berated Rome's male citizens for "betraying [their] country by rendering her barren and childless."

Rome and Assyria were both imperial powers that relied on a constant supply of male citizens to serve in their armed forces. Banning abortion protected the state's right to future citizens.

Life didn't always begin at conception

Ancient societies didn't believe fetuses were alive in any meaningful way. They understood fetal development from conception to birth as a gradual process.

The movement to ban abortion in modern times has been led largely by Catholic, Latter-Day Saints, and evangelical advocacy groups, but even Christian theologians haven't always classified the fetus as a person from the moment of conception.

For medieval Europeans, the critical turning point wasn't conception but ensoulment, when the fetus' soul entered its body. Before ensoulment, the fetus was imagined as something more like a plant than a person – it had a form but no consciousness.

Some Christians believed ensoulment didn't occur until a baby was born and drew its first breath, based on Genesis 2:7, which says God "breathed into [man's] nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living soul."

Most, though, agreed the soul entered the body at the quickening, when the fetus first begins to move in the womb.

Before that time, abortion wasn't generally considered criminal in either church or common law.

The path to modern abortion laws

Abortion before the quickening wasn't outlawed in the British empire until 1837. A newly self-governing Canada passed its own law against abortion in 1869, the same year Pope Pius IX declared all abortion murder in the eyes of the Catholic church.

The push to criminalize abortion in the nineteenth century was driven by several factors.

As medicine became a more organized profession, doctors began to advocate against abortion and against using the quickening as an indicator of fetal life. Their motivations may have had more to do with economics than science.

Leading up to the 1800s, abortions were mainly the province of midwives. By outlawing abortion, doctors not only established themselves as scientifically superior to these traditional health-care providers, they drummed up business. More women having babies meant more clients for male obstetricians.

Like their ancient Roman counterparts, lawmakers were also concerned with low birth rates. European nations wanted to keep pace with the population growth of their political rivals. The fact that most abortions were procured by married, middle-class white women didn't escape their notice, either.

At a time when concepts of eugenics and racial purity were on the rise, some anti-abortion activists worried the white population would soon be outnumbered unless white women were prevented from controlling their fertility.

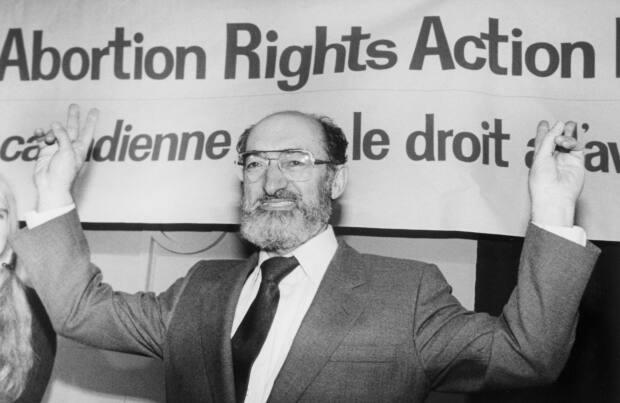

Abortions were illegal under Canadian law for just a century, until in 1969 the government

decriminalized those performed for the sake of a woman's life or health.

Eventually, in 1988, the Supreme Court struck down Canada's anti-abortion law, declaring it unconstitutional because it infringed on a woman's "life, liberty and security of person."

Abortion's place in modern law

While abortion may remain a moral issue for some Canadians, laws don't exist to police our morality.

Many things people consider immoral aren't illegal: lying, breaking a promise, acting selfishly,

committing adultery.

The purpose of our legal system is to protect our safety, our property, and our personal freedoms so we can live peacefully together in a society. Many people would argue we should limit the scope of our laws as much as possible so each of us can live our lives as we think best.

Although 57 per cent of Canadians believe we should have a law protecting abortion, many abortion advocates disagree.

After all, no other medical procedures are protected by law, so why bring politicians and judges into this private health matter?

From a historical perspective, abortion laws have been the exception, not the rule.

The way abortion is handled in other countries today shouldn't mislead us into thinking that Canada needs abortion legislation, too, even to protect our right to the procedure.

As history has shown, some decisions are better left to the private sphere.