New Brunswick artist has mapped out plans to dig for smooth, glassy treasure

A New Brunswick ceramic artist is on a geological treasure hunt for local material for his craft.

Michael Wood has a pottery studio at his home on the Petitcodiac River in Salisbury, works as the ceramic technician at the Arts and Culture Centre in Dieppe and was a recent contestant on the CBC reality show, The Great Canadian Pottery Throw Down.

He's now working on a project to create a made-in-New Brunswick ceramic glaze, the glassy coating used to seal earthenware items, such as dishes and vases.

Wood got the idea for the project while thinking about the roots of pottery. Historically, potters would set up near water and a source of clay, he said.

Given the abundance of resources in New Brunswick, Wood thought there must be a way to source at least some of his materials more locally, instead of ordering them from all over the world.

Michael Wood presents the ceramic vase and flowers he created during the CBC reality show competition The Great Canadian Pottery Throw Down, as part of a challenge on the theme of a hometown tribute. His clay included crushed up rocks from his driveway. (Great Canadian Pottery Throw Down/CBC)

Local clay has a high iron content so it melts at a lower temperature than the material he prefers for the body of his pieces.

But there is plenty of granite around that he thinks might be good for making glazes.

Granites are a main source for all four of main elements in glazes, he said — which are silica, alumina, alkali metals and alkaline earths.

"We can basically go out and collect rocks, crush them down and depending on the composition we might need to add a couple more things, but ultimately it will turn into glass when we heat it up to high temperatures."

"The hard part is really just finding the right rocks and doing the testing."

This is Wood's set up when he's experimenting with different materials to create a glaze. (Submitted by Michael Wood)

Wood began his search in the provincial archives. He looked up historic mines and geological maps and read up on the types of rocks found in different areas, and he's made a list of places he plans to go this summer to dig for rock samples.

Processing the rocks involves using a ball mill or a hammer mill to crush them down to fine powder.

The melting point for powder is much lower than it would be for solid rock, and various powders can be mixed in certain proportions for melting, he explained.

Wood will be looking for rocks that can produce a durable, uniform, glossy and impermeable surface.

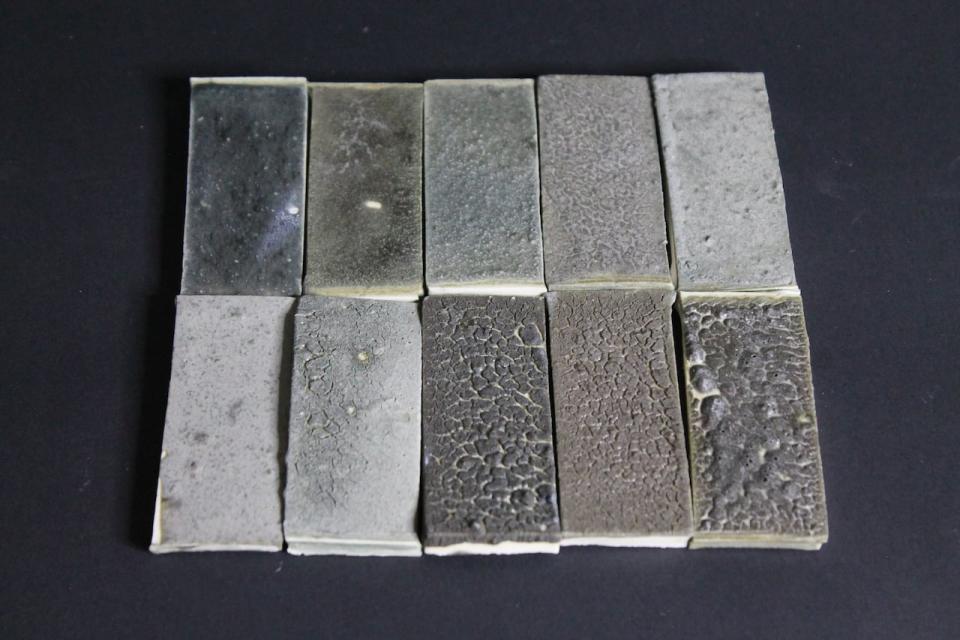

Here are how some of Wood's previously tested glaze experiments turned out. (Submitted by Michael Wood)

"Clay can be really porous. And so you really want to protect that clay from getting moisture," he said.

"If you think of terracotta pots, when you put them outside in the winter, if water gets into them, they often crack and break when the water expands."

He's planning on conducting 200 to 300 tests and expects maybe 10 per cent will be successful.

"There's definitely going to be some error and some some trial," he said.

"It's through that process that you do get something that's good. Failure is part of the process."

Wood has made his own glazes before.

Most recently he used ash he'd reduced from the deadfall of several types of trees, including red maples, yellow birches and oaks.

"You get different colours of glazes and different textures based on the minerals that they're made up of."

He used it on porcelain tree-stump pieces to, in an artistic sense, "recreate the forest."

Wood said these pieces are glazed with materials that include hand-harvested salt from the Northumberland Strait and softwoods from the Acadian forest. (Submitted by Michael Wood)

The second phase of his project will be holding a workshop to show other ceramic artists how to apply this concept to their work.

"That way we can kind of create a more sustainable way forward," he said.

Albert County potter Judy Tate said she'd be interested in signing up for that workshop.

Tate is one of a few artists who work with local New Brunswick clay and she's been doing so for about 24 years.

She gathers her material by the tonne when she knows a landowner who has an excavation permit.

She dries it out, breaks it down in a ball mill, sifts it through a screen, mixes it with water and lets it settle in tubs, before feeding it into machine that churns it "into a lovely fine working material."

Tate fashions local clay into funeral urns, sugar savers, mugs, vases, wall sconces, dishes and platters.

Judy Tate makes pottery using local clay. Her business is called the Albert County Clay Company. It’s in an old community hall on Albert Mines Road in Curryville, near Hopewell Rocks. Tate said tourists love being able to see how the pottery-making process works and take home a souvenir from the region. (Albert County Clay Company/Facebook)

When she first moved to the area, she was struck by the large amount of clay she saw along the coast.

Her pottery training had been in Stoke-on-Trent, an area of England which became a global hotbed of pottery manufacturing because of its local coal and clay resources.

Tate thought someone should be using the clay that was present in such abundance in New Brunswick.

None of her pottery friends were very keen on the idea or the time-consuming process, but Tate received encouragement to give it a try.

What she's been able to create is "a little different from most pottery," she said.

"I found that people who come to visit are very, very interested in the clay and being offered pottery that is made from that clay."

She thinks a locally sourced glaze, like what Wood is trying to develop, would be "a nice fit" with her product.

"I think that's the way we should be going — using our natural resources instead of buying it from all over the place. We need to be more conservative with our spending and manufacturing. This is great that he's experimenting in this way."

There are a few local clay deposits with lower iron content, said Wood, and he plans to use some for glazes.

Ideally, he hopes to find good rocks at an active mine, because that could provide an easily accessible supply.

There are a few in his area that seem promising.

Tailings from mines in the Sussex area might work, Tate suggested, because they have lower iron content and would produce a lighter coloured glaze.

If the best glaze rocks end up being at a mine that has shut down, it will be more complicated and labour intensive to secure a ready supply.

There are four contestants left in The Great Canadian Pottery Throwdown, including Elsa Valiñas, of Fredericton. The last two episodes are scheduled for March 28 and April 4 at 8 p.m. on CBC TV and will be available to stream on those dates on CBC Gem.