NC church was once a courthouse. Now, it’s part of movement to preserve Black history.

Myrtle Mayo remembers when Dickerson Chapel held “great revivals” that filled the sanctuary and when Hillsborough’s Black residents met there in the 1950s and 1960s to discuss their common purpose in the fight for justice.

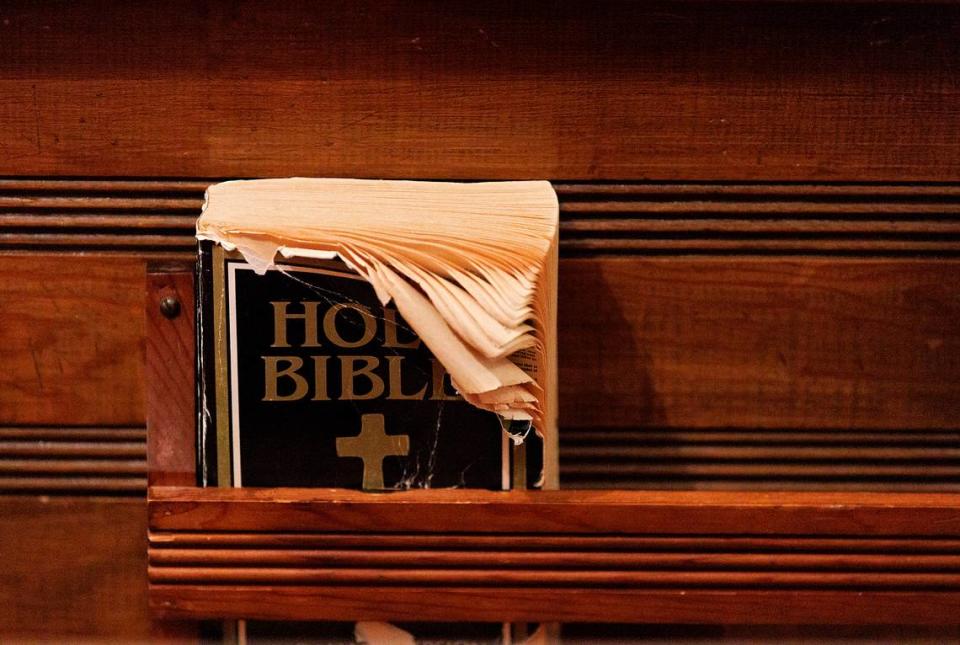

The pews are less crowded now, and the wooden floors buckle and slope.

But Dickerson Chapel AME Church still stands, “and its purpose has been good,” said Mayo, 92.

And with a lot of love and an infusion of money for repairs, it could stand for another 234 years, she and others said.

Built in 1790, the building originally housed Orange County’s courts, where Black people were sold into slavery, punished for crimes they often didn’t commit and watched as Black and Indigenous children born free were taken away to be involuntary “apprentices.”

In 1844, after the Historic Orange County Courthouse that stands today was built, the older building was sold to the Rev. Elias Dodson and moved to the corner of North Churton and East Queen streets to serve a white Baptist congregation.

In 1862, local Quakers bought the building, which by then was hosting abolitionist meetings and a woodworking shop. They operated a Freedman’s School for over 300 Black children and adults there until 1886, when it was sold to the African Methodist Episcopal deacons who founded Dickerson Chapel.

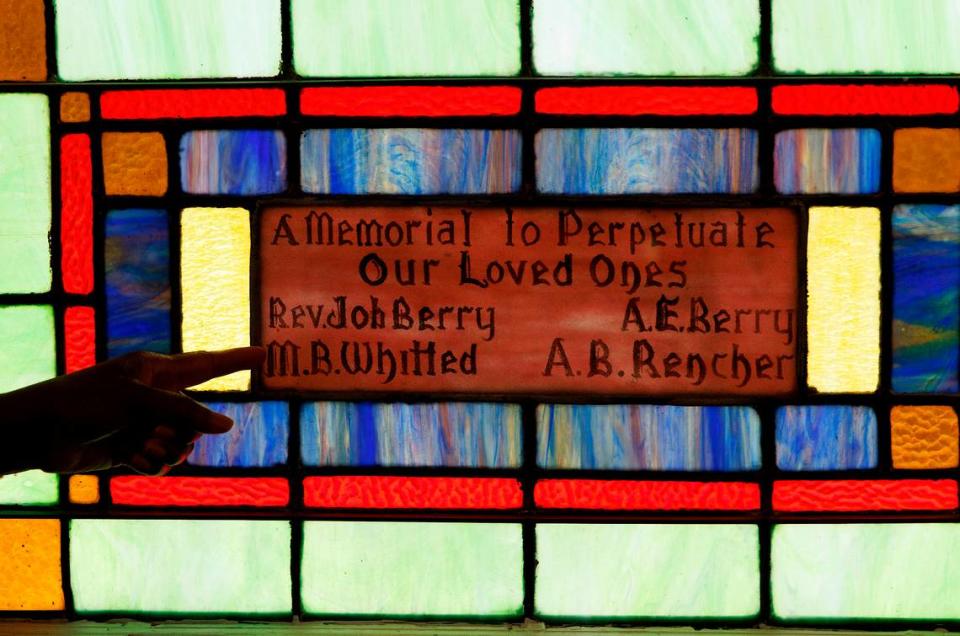

The original timber frame, built by enslaved hands and still visible in the basement, was encased in a brick facade, and renovations were made over the years. Donations bought double-hung, stained-glass windows, some bearing the names of founding families.

“It has had its past, and it has (seen) things that none of us could even imagine it has endured,” said the Rev. Toma Shaw, who has led the church for more than two years. “But by the grace of God and the grace of the people and the history of those that lived here … we’ve endured each one of those things.”

Black, Indigenous voices telling their own stories

Shaw’s congregation is working with the Alliance for Historic Hillsborough, Preservation Fund Hillsborough and the Orange County Historical Museum to preserve Dickerson Chapel. A display with the church’s story was added near the front steps last year, and it is one of 10 stops on the town’s “Telling the Full Story” project walking tour.

“We are really focusing on trying to restore it, revitalize it and just get the community encouraged around it,” Shaw said. “We believe — and I believe — that once the community rallies around this church, it will actually do something in the entire community, because this church is the community.”

That’s a refrain echoing across North Carolina as groups — from historical associations and museums to arts organizations and citizens — identify and preserve the stories of marginalized communities through their own memories and words.

In Hillsborough, Black and Indigenous residents worked with white folks to identify the first 10 tour stops. They secured a $25,000 National Trust grant to pay for the work, which includes stories, events and videos. With more donations, they could add more stops and interpretive signs, said Amanda Boyd, executive director of the Alliance for Historic Hillsborough.

“People love to come to Hillsborough to explore all the quaintness that we offer. We want them to be able to explore and understand all of our community, not just the history that has been told before,” Boyd said. “If every community could learn more about their culture and the people that have been here and made Hillsborough ... what it is, that could paint a truer picture.”

What are the challenges in this work?

Some volunteers and grassroots groups have stepped forward to preserve Black history, but they often lack the experience to know what needs to be preserved and what help is available, said Adrienne Nirdé, director of the N.C. African American Heritage Commission.

The commission, in addition to its own projects, is a resource for those groups and connects them to others, she said. The partnerships can spark creative ways of telling Black stories that capture the attention of new audiences, she said.

Shaw University sociology professor Valerie Ann Johnson said her parents got her interested in Black history by encouraging her to look things up in “International Library of Negro Life and History” encyclopedias. Her current work and research stokes the fire, said Johnson, the university’s dean of Arts, Sciences and Humanities.

Many “lost” Black stories can be found in Black presses and newspapers dating back as early as the 1700s, while others take some digging. Sometimes enslavement and oppression cut family ties to the stories or the people who could tell the stories didn’t think they were important enough to be told, she said.

Oral histories, which are being lost as older generations die, and missing details that attract new and younger audiences are key to telling more complete stories now, Nirdé and others said.

“(Older folks) might be holding on to all kinds of important history, but nobody ever thought to ask them,” Nirdé said.

Telling complete stories is not about being “woke,” Johnson added, referring to a term of derision used sometimes in conservative circles.

“When you leave out aspects of the story, even the painful parts — especially the painful parts — then you miss” parts of our American story, Johnson said.

Old buildings are greater than architecture

Historic buildings like Dickerson Chapel are also important because they reflect the social structures that made them necessary, Johnson said.

The Warren County Community Center, where the Black community came together in 1934, is a good example of that, she said. The center, built with 80,000 handmade bricks, grew out of necessity, because Black residents didn’t have access to public restrooms in downtown Warrenton. A library and community center were added later.

Historic buildings are more than the architecture, Johnson said, because they reflect the lives and accomplishments of people inside.

Dickerson Chapel and nearby Mt. Bright Baptist Church played key roles in the Civil Rights Movement. Both were also centerpieces of a rich community life, said Mayo, who joined the Dickerson congregation in 1955.

The Ku Klux Klan was active in Hillsborough at the time, burning crosses and terrorizing the Black community. Mayo recalled times when the group wore black masks to march at night in the Old Slave Cemetery on Margaret Lane, a historically Black area of town.

Some of those same people owned shops downtown, she said, and though most were nice to her, she was warned to be careful.

Horace Johnson Jr., a member of the committee trying to save Dickerson Chapel and one of the first Black students to integrate Orange County Schools, also remembers those days.

His father, Horace Johnson Sr., was a civil rights leader who helped to break down color barriers and promote school integration and voting rights — work that got the attention of white supremacists who at one point chased protesters at gunpoint to his home in 1968.

In 1989, Johnson wore a bulletproof vest after being elected the town’s first and only Black mayor. He remained in office for 14 years.

“A lot of things have changed from then until now, and a lot of things haven’t changed from then until now,” Johnson Jr. said. “I think looking at all sides … of the story and the history provides a more rounded education that expresses empathy.”

Important lessons for future generations

The work that professional historians and community volunteers are doing will enable the next generation “to know their history and to be able to learn from it and know that they are capable of great things,” Nirdé said.

It’s not just museums and historical sites, but also festivals and tours focused on telling stories from a local perspective, she said, pointing to the N.C. Rice Festival in Brunswick County, the Ocean City Jazz Festival in North Topsail Beach and the African American Experience of Northeast North Carolina as just a few examples.

“That’s the thing about North Carolina,” Nirdé said. “We’ve just got so much rich history here. Whether people know about it yet or not, there’s just endless opportunities to explore.”

Uniquely NC is a News & Observer subscriber collection of moments, landmarks and personalities that define the uniqueness (and pride) of why we live in the Triangle and North Carolina.