How a no-take zone revived a Scottish fishery devastated by dredgers

After the government allowed trawlers to come closer to Scottish shores in 1984, the marine ecosystem around the Isle of Arran steadily collapsed, as bottom-trawlers and dredgers intensively combed the seabed with their vibrating spikes.

Now, more than 30 years later and following the interventions of local residents, there has been a dramatic revival in species of mollusks and finfish.

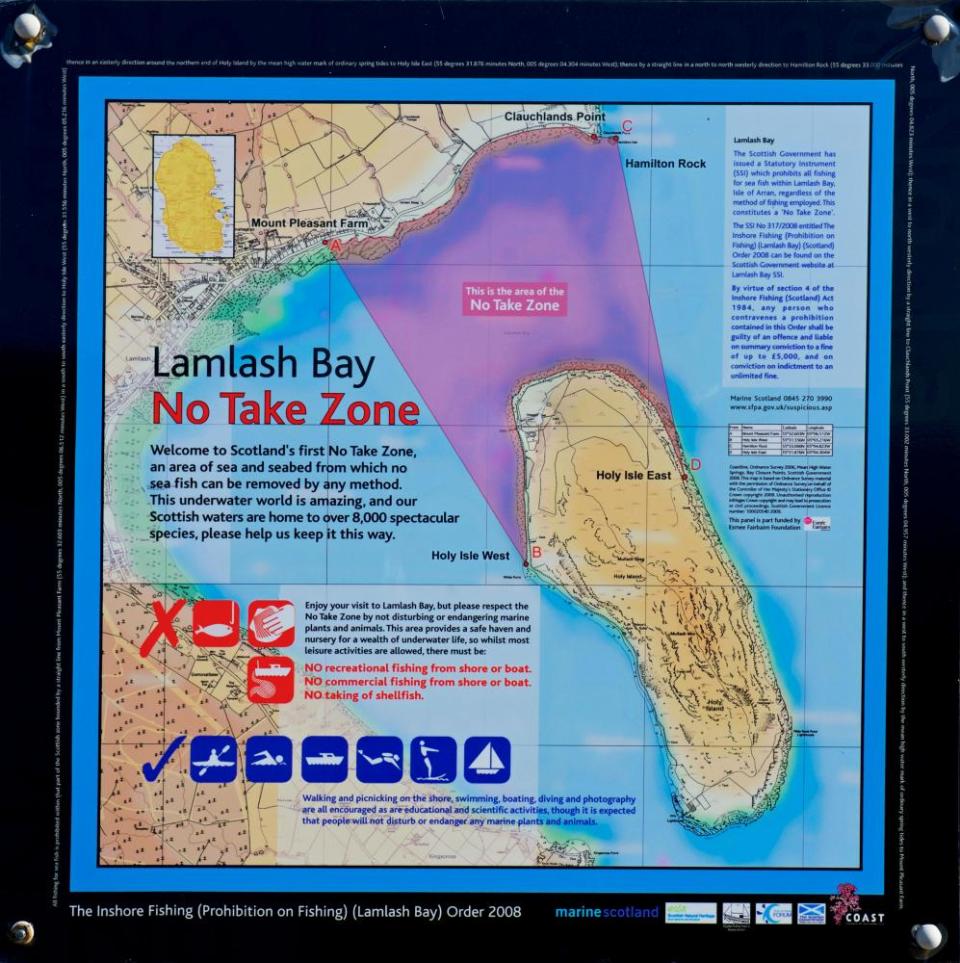

A “no-take zone” implemented here in 2008 – after a community-based campaign to lobby the Scottish government – has been a huge success, according to a new report that shows a substantial increase in biodiversity.

Lobsters are now over four times more abundant in the no-take zone, a 2.67 sq km area where fishing is not allowed, than in adjacent areas. The research, led by the University of York, shows king scallop density is four times higher than in 2013, carbon-absorbing weeds have returned to the seabed, and the area is now a nursery for juvenile fish, especially cod. The lobsters in the zone produce six times more eggs than outside it.

“The seabed habitats are springing up,” says Howard Wood, co-founder of the Community of Arran Seabed Trust (Coast). “Without destructive forms of fishing, this amazing, complex seabed allows more species to inhabit, hide and feed. You can see what happens when nature is allowed to thrive.”

Wood, a diver who was awarded an OBE for services to the environment, led the successful lobbying for no-take zones along with fellow local resident Don MacNeish, who witnessed their transformative effect in New Zealand. Now they are calling for Holyrood and Westminster to sanction more no-take zones around the UK.

Any environment can benefit from better protection, and every community has the right to a better environment if they want one

Howard Wood, Coast

In contrast to humans, who become less fertile as they grow older, many species of fish spend more of their energy producing eggs as they age. This is one reason proponents say no-take zones – also known as highly protected marine areas (HPMAs) – are so crucial to allowing species repopulation.

There are currently four such zones in the UK: in the Medway estuary, at Flamborough Head on the north Yorkshire coast, and near Lundy island, Devon – which has seen a remarkable rise in the lobster population.

The UK government is currently examining whether to introduce no-take zones in vulnerable English sea areas, with a review due to be published this spring. There are already about 350 marine protection areas, but as they allow fishing, many observers think they do little to improve degraded ecosystems.

“We have thousands of square kilometres of ‘paper parks’, which give the appearance of protection but do little in practice,” says Jean-Luc Solandt of the Marine Conservation Society. “It is the unfortunate case that the government is doing very little to protect our seas.”

Trawling, for instance, is banned in MPAs, but there are many reports that this is not effectively enforced. “People are fishing with impunity and we find it flabbergasting that the protected areas are not actually protected,” says Solandt.

Last month, marine conservation charity Open Seas accused the Scottish government of “sitting on its hands in the wake of repeated instances of illegal scallop dredging” in MPA’s.

More than 98% of British scallops – the majority of which are exported to Europe – are caught using dredges that unearth the molluscs from the seabed; smashing sea urchins, tearing limbs off starfish and often leaving a trail of collateral damage, though the proportion caught in protected areas is unclear.

But the £120m sector employs about 600 people directly, and another 750 in processing jobs, meaning any further changes would inevitably put some people out of work.

A spokesperson for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs blamed the EU for the failures in marine conservation. “Currently the Common Fisheries Policy restricts our ability to implement tougher protections but leaving the EU and taking back control of our waters as an independent coastal state gives us the opportunity to introduce stronger measures,” she says.

“Targeted HPMAs could complement the existing network of MPAs and allow vulnerable marine wildlife to fully recover, free from all damaging human activities, with the aim of leaving nature in a better state than we found it.”

In New Zealand, Australia, the US and elsewhere, large parts of the sea are subject to comprehensive fishing bans.

Such zones should be expanded to at least one-quarter of all UK waters, say conservationists. This would allow stocks of fish such as North Sea cod – which have fallen by almost a third since 2015 – to replenish.

The National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations argued that no-take zones were not needed, as current protections were sufficient. “Contrary to claims that they are ‘paper parks’, once steps have been completed to put in place appropriate management, there is little doubt that [MPAs] will provide ample levels of protection,” assistant chief executive Dale Rodmell says.

He says it will not matter how many crabs and lobsters live in the sea if coastal communities cannot make a living from them.

But it is precisely the interests of the community that Wood has in mind. “Coast’s most important message is that any environment can benefit from better protection, and every community has the right to a better environment if they want one,” he says.

“If that is embraced on a global scale then we truly will see a sea change in the health of our seas.”