Ontario does not keep stats on fentanyl deaths caused through prescription use

A Mississauga man whose wife died after years of fentanyl use can't believe the province doesn't track overdoses involving the prescription use of the drug and those involving the illegal street use of such opioids.

Greg Carney, 62, says in the middle of a declared opioid crisis, specifically tracking deaths from prescription use might provide a clearer picture of who is dying in Ontario and how.

That could help save lives, he says.

On the morning of June 16, 2016, Carney found his 60-year-old wife, Ann, on the living room couch. At first he thought she was sleeping and didn't bother her until mid-morning, when he decided it was time for her get up.

"I tried shaking her and that and when I saw the colour of her skin, I thought something was wrong," he said. When he couldn't find a pulse, he called 9-11.

Firefighters, police and paramedics arrived, but Carney says there was little they could do. "Paramedics took me into the kitchen sat me down and told me she had indeed passed."

As the family grieved and burial arrangements were made for the mother of three and grandmother of one, the cause of her death remained a mystery.

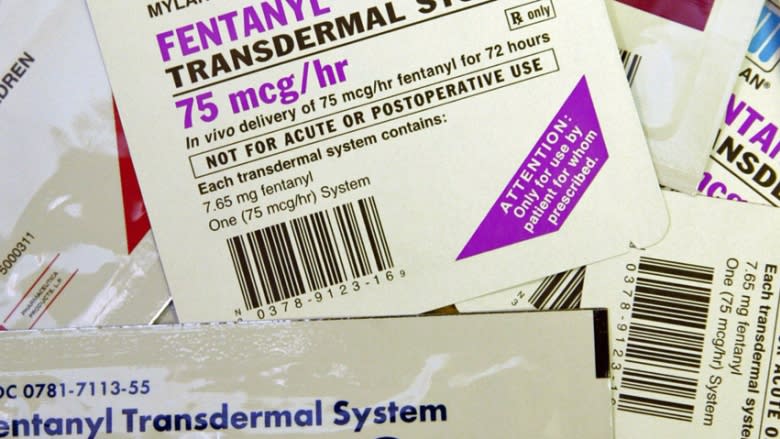

Six months later, a coroner's toxicology report revealed she had two-and-a-half times the lethal dose of fentanyl in her system. Ann Carney became part of a grim statistic: she was one 76 opioid-related deaths in Ontario that month.

'How did this happen?'

"How? How did this happen?" her husband asked.

Carney said his wife was not a recreational drug user, which is what many assume is the profile of the typical opioid overdose victim. She was legally prescribed fentanyl to deal with chronic nerve pain, the result of a botched hip operation.

"The touch of anything on her skin, the touch or the wind or the sun or anything that she felt sensation would cause pain. She described it sort of like somebody rubbing sandpaper on the the inside of her leg," said Carney.

After seeing many doctors and specialists over the years, Carney said she finally went to a pain clinic in search of relief.

"The fentanyl patch was a last resort because of all the other pain meds they'd tried," he said.

Fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine and up to 50 times stronger than heroin and has become a popular treatment for chronic pain.

Carney said his wife was a trained nurse and knew how to administer her own medication. Still, over the five years she was on the patch, there were concerns.

Husband had concerns about fentanyl patch

"She was having these episodes of passing out quite a bit and no doctor could pinpoint the problem," he said.

He suspected the fentanyl and said about three years ago, on the advice of doctors at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, she cut her dose in half — to 50-microgram patches.

So Carney was surprised to learn from the coroner's report that she died from an overdose of the drug.

"I didn't know how that could be possible. She had taken the patches as prescribed ... To have that kind of overdose, she'd have to be wearing a dozen patches at a time."

He was also surprised to learn that the province does not track the number of deaths due to opioids that were from prescribed sources.

"I had asked about the coroner's report and how many people die of an overdose of fentanyl, and how many are street drugs and how many are prescribed — they don't differentiate."

Carney says that means the province — which is hoping to head off a public-health crisis — has an incomplete picture of the problem here.

Province knows it needs to collect more data

In a statement, Ministry of Health spokesperson David Jensen said Ontario is working to strengthen surveillance and monitoring of opioid use, disorder and overdose.

"The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is working collaboratively with the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario to link coroner-related data with opioid prescription data from the Narcotic Monitoring System."

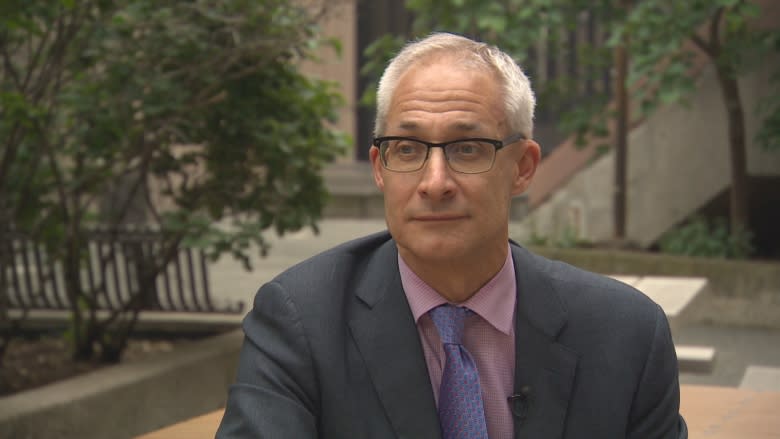

Ontario's chief coroner, Dr. Dirk Huyer, said the province knows its method of collecting data desperately needs updating.

"Unfortunately we don't have that easy availability [of those numbers]. We do not have the robustness of the information that we would like to have in order to better answer the question the family has, which is: how common is this?" said Huyer.

"I don't have the ability to be specific about the commonness of this, certainly we know it happens, we just don't know the percentage compared to what's occurring on the streets."

Huyer adds the methodology for collecting such basic data has limited how detailed and timely those numbers are. For example, to find out how many opioid related deaths there were required evaluating all the investigations for the entire year.

This spring, Huyer said, the province began an overhaul of the way it collects and analyzes data on opioid overdoses and deaths in an effort to address the lack of detailed timely numbers.

As of April 1, all Ontario hospitals began reporting opioid overdoses on a weekly basis. And Public Health Ontario has a tracking tool that makes the most up-to-date numbers publicly accessible.

As for the number of deaths involving prescribed opioids, Huyer said: "We know there's a concern about prescriptions and that has been talked about in the past."

Huyer said in May, updated guidelines for prescribing opioids were released to encourage doctors to avoid giving the powerful narcotics as a first-line treatment to patients with chronic pain.

"We know that, in Ontario, we are one of the top prescribers in the world of opioids for non-cancer pain. We are well aware of that," said Huyer.

Still, Carney thinks more accurate numbers will prove what he suspects: "It's a powerful drug. Even if you don't abuse it, you could die."