OPINION | Why Alberta won't have a PST without electoral reform

This column is an opinion from Max Fawcett, a freelance writer and the former editor of Alberta Oil magazine.

Desperate times may call for desperate measures, but apparently they're not desperate enough yet in Alberta for our political leaders to seriously consider a sales tax.

Never mind that the United Conservative Party's government's latest budget contained a nearly $20-billion deficit, one that will add to a rapidly growing pile of provincial debt that's expected to hit $115 billion by the end of the next fiscal year.

No, rather than taking the advice of virtually every economist and fiscal expert in the province — including the Business Council of Alberta, which isn't exactly a pro-tax organization — and prepare Albertans to finally pay for the services they receive, Premier Jason Kenney doubled down on the status quo.

"The last thing Albertans need in this time of economic uncertainty is new taxes," he tweeted.

But, of course, Albertans haven't embraced new taxes during times of relative economic certainty, either. And therein lies the rub: Albertans have grown accustomed to running up a tab that was paid off using their province's oil and gas royalty revenues.

Hard choices

But those revenues started drying up years ago, back when Stephen Harper was prime minister and Jim Prentice was premier. As the BCA's recent report suggests, it's time for all of us to look in the collective mirror and make some hard choices.

"A well-run, high-tax, high-spend government can function well and generate economic growth and prosperity," it says.

"The same is true of a low-tax, low-spend government. We cannot, however, sustainably run a high-spend, low-tax government in the province. This option was available for a period of time when resource revenues were high, but it would be inadvisable — to say nothing of fiscally imprudent — to count on such an approach succeeding in the future."

In fairness to Kenney, it's not like the official opposition is saying anything different when it comes to the idea of a sales tax. Indeed, NDP Leader Rachel Notley even said she agreed with the premier that now wasn't the time to introduce a provincial sales tax.

The irony here is that while they may share the same opposition to a PST in public, in private they almost certainly share a belief that new revenue measures of some sort are necessary.

So how can they build a bridge between those two positions before the bond markets come calling for Alberta the way they did in the 1990s for the federal government? The best way might be with something that's nearly as unpopular as a sales tax in Alberta: electoral reform.

That's an idea that both Kenney and Notley have endorsed, albeit at points in their career where it would have more obviously aided their partisan interests.

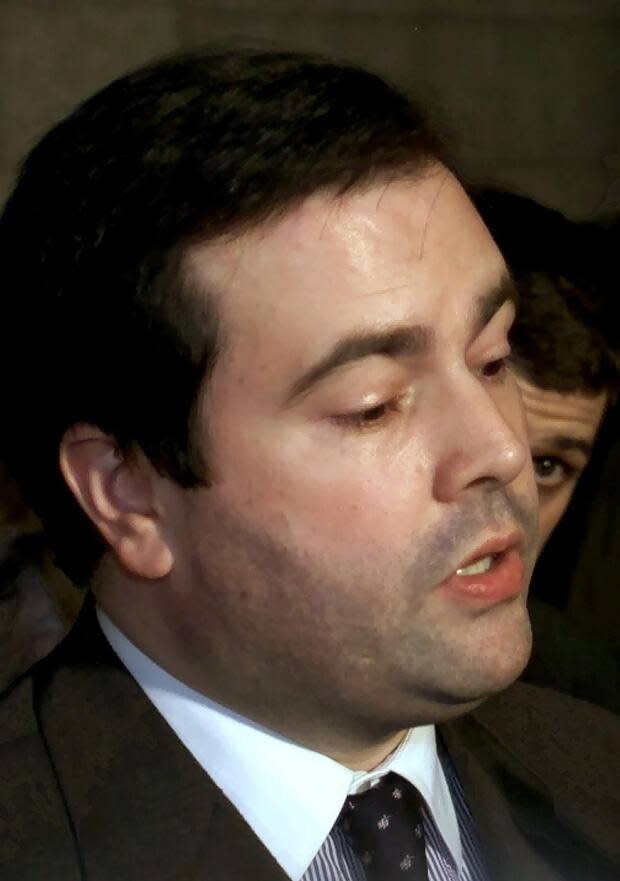

Back in 2001, Kenney — then a Canadian Alliance MP — spoke in favour of an NDP motion for a special all-party committee to study the merits of proportional systems, noting that "in the last two elections respectively, the Liberal Party earned 38 per cent and 41 per cent of the popular vote, which was far short of majority. Yet, with roughly 60 per cent of Canadians opposing its program, it managed to completely monopolize political power in the country."

Notley's NDP, meanwhile, had proportional representation as a policy plank in its platform in the 2012 election, only to remove it in early 2015 when it became clear the governing Tories might actually lose.

Once in power, the Notley NDP showed no real interest in changing the electoral system that helped give them a majority of the seats with a minority of the votes.

As ever, if there's one thing that's universally true in Canadian politics, it's that a party's fondness for electoral reform is inversely correlated to its proximity to power.

But while proportional representation may be poison to most governments hoping to wield power, Alberta's situation may be uniquely suited to it. After all, it might allow the province to finally cut the Gordian knot that Ralph Klein helped tie around the government's hands a generation ago when it comes to fiscal policy.

Beneficial outcomes

No party wants to be seen campaigning for a sales tax, and it seems vanishingly unlikely that one could form a government by doing so. But if, in the near future, an election was conducted under a system of proportional representation, it stands to reason that an explicitly (and perhaps exclusively) pro-PST party could attract somewhere between 10 and 20 per cent of the vote.

That would have two beneficial outcomes, as far as the province's fiscal framework is concerned.

First, it would force the major parties to take the issue more seriously. And second, if the election produced a legislature without a party holding more than 50 per cent of the seats, as proportional systems tend to (and as the 2015 election would have), it could give the PST Party the ability to play kingmaker — for a very specific price.

That, in turn, would give their potential governing partner, whoever it might be, the political cover they need to do what needs doing.

First things first, though. In order to conduct an election using a proportional system, you need a government that's willing to implement it in the first place.

It's highly unlikely that Kenney would do that as premier, given that it would risk fragmenting the coalition that he came back to Alberta in order to build.

But while Alberta's NDP shied away from proportional representation when it became clear it had a chance to win in 2015, perhaps this time could be different. It's an idea that aligns with the party's own values and beliefs, and its implementation could help break the hammer-lock that conservatives tend to have on Alberta politics by helping the NDP attract votes in the one place it needs them most: Calgary.

In order to form a government in 2023, the Notley NDP needs to do at least as well in Calgary as it did in 2015, if not better. And what better way to appeal to former Progressive Conservative voters in the city than with the prospect of being able to vote for Progressive Conservative candidates in the future?

A legacy to match Lougheed's

Under a system of proportional representation, PCs could theoretically reconstitute a more moderate conservative party, one that wouldn't face the obstacles that stand in its way under a first-past-the-post system.

For those who oppose the choices the UCP has made but remain wary of the ones the NDP might make themselves, the promise of electoral reform could be just what they need to take the leap.

And while endorsing and implementing electoral reform might mean the Alberta NDP never forms another majority government again, it could allow Notley to leave a legacy that matches Peter Lougheed's — one that's much bigger than just a sales tax: the creation of a political system that's more responsive to Alberta's needs, more attuned to its preferences, and more able to represent the diversity of ideas and people that the province contains.

That's an Alberta advantage worth bragging about.

This column is an opinion. For more information about our commentary section, please read our FAQ.

More great reads from the Road Ahead: