New Caledonia Violence Cuts Macron’s Global Ambition Down to Size

(Bloomberg) -- The image of New Caledonia as an idyllic, palm-fringed slice of France in the Pacific Ocean has been shattered by an outbreak of violence, undercutting President Emmanuel Macron’s efforts to retain, and even extend, Paris’ influence overseas.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Key Engines of US Consumer Spending Are Losing Steam All at Once

GameStop Shares Surge as Gill’s Reddit Return Shows Huge Bet

Mnuchin Chases Wall Street Glory With His War Chest of Foreign Money

Homebuyers Are Starting to Revolt Over Steep Prices Across US

AMLO Protege Sheinbaum Becomes First Female President in Mexico

Just over a week into the unrest, Macron made the 17,000-km (11,000 mile) trip to the archipelago, hoping to restore confidence at a time when China and other powers are eager to press their advantage in the region, especially in resource-rich islands like these. Instead, the turbulence — rooted in long-standing economic strain and triggered by contentious new rules to extend the voting population — has developed into a lasting problem for the Elysee.

Even after a state of emergency was lifted last Tuesday, some districts on the outskirts of the capital Nouméa remain all but cut off by makeshift barriers, burnt-out schools are shuttered, while obstructed roads, scarce petrol and a curfew continue to make movement difficult. Hundreds of businesses have been looted, causing as much as €1 billion ($1.1 billion) of damage.

New Caledonia’s nickel mines, vital to employment in this territory of 270,000, were already struggling with low prices and are now barely operating. The visitors who usually flock to beaches along a turquoise coast have been evacuated by military aircraft, while the main airport remains closed. Even in the most exclusive areas in Nouméa’s south, store supplies are sparse and residents have formed night-watch groups to protect homes and businesses from ongoing arson. Racially tinged exchanges and disinformation fill social media.

Ties between the metropole and this Pacific archipelago, with a population roughly split between the indigenous Kanak and locals of European, Asian and other descent, have long been fraught. But not since a Kanak uprising in the 1980s have relations between communities been similarly strained. At least seven people have died in the violence, including two policemen.

“Social and economic inequalities have led to this situation. Kanak people are not really as integrated in the economy of the country and part of the population has begun to question the model,” said Robert Kakue, a 35-year-old Kanak entrepreneur in Nouméa.

Referring to fiscal transfers to majority Kanak provinces, education and infrastructure initiatives, he added, “Over 30 years a lot of things have been done, but we are starting to see that was not enough.”

Macron’s visit to New Caledonia, just before a key summit with his German counterpart in Berlin, was intended as a show of solidarity and a means of encouraging dialogue between rival political leaders. But a stopover lasting less than 24 hours was seen by many on the ground as out of touch, even dismissive, of a deep crisis prompted by electoral reforms opposed by the pro-independence camp.

“The visit was intended to reassure that order would be restored,” said Roch Wamytan, president of New Caledonia’s congress and leader of Union Caledonienne, the oldest pro-independence party. “But it was for them, not really for us. For us, they sent the military, the police and not much more.”

Nearly 500 additional gendarmes arrived last week, on top of more than 3,000 security forces already on the ground.

Macron acknowledged a crippled economy that has long failed to deliver equitably even after funds and initiatives multiplied — but announced no substantial new measures.

“New Imperialism”

Trouble in New Caledonia comes with serious consequences.

France sees itself not only as a major power in the Pacific and Indian oceans, but as a resident power. Its territories in the region, remnants of a vast colonial empire, are home to 1.6 million of its citizens and account for nearly 60% of its permanent overseas military presence. Attempts by Paris to boost its engagement — and protect its interests from what Macron has called China’s “new imperialism” — were already dealt a blow in 2021 when it was excluded from an expanded US, UK and Australian defense pact.

Efforts to keep Paris’s influence from waning are faltering elsewhere too, with ties fraying in North Africa and the Sahel, areas it once considered its backyard.

France’s hold on New Caledonia dates back to 1853, when it was seized in part to preempt any move by the British. The Kanak people were moved to reservations, and a penal colony and port were set up. The archipelago became an overseas territory in 1946, and migration was encouraged from the 1960s. In the late 1970s, some areas were returned to the indigenous community as part of land reform.

Today, its residents hold French nationality. The territory has many of the trappings of metropolitan life, but is also semi-autonomous and, after agreements in 1988 and 1998 which aimed to give Kanak more political power, has had a pro-independence president since 2021.

Still, neither that nor expansive fiscal support from the metropole have rectified economic gaps, rendered more painful by rising prices and a deteriorating economy as New Caledonia’s nickel industry becomes increasingly unprofitable.

The source of about a fifth of private sector jobs, its smelters and mines now face an existential threat from Indonesia, where a Chinese-backed industry is booming.

A Fragile Economy

“New Caledonia’s economy was already left fragile by the deep crisis in nickel over the past few years,” said Mimsy Daly, businesswoman and head of the local branch of business lobby Medef, whose own family has been in New Caledonia since the 19th century. The outbreak of violence, she said, means hundreds of companies have been left on the brink of bankruptcy, and thousands of jobs have been lost.

“We need state support to help us rebuild, but also to find a lasting peace,” she said. “We want the government to widen discussions to civil society. We cannot leave this to politicians who have clearly failed to build a plan for this territory.”

May’s violence began after France began pushing through a law to reform the electorate, giving new arrivals from the mainland and elsewhere the vote after 10 years’ residency.

Champions of the measure say that the current situation was untenable, given the number of people in New Caledonia who do not have the right to vote despite decades in the territory. But for many Kanak, the change without prior political accord was a reversal of past agreements — and a policy that harked back to past efforts to dilute the indigenous population.

“There was a fear for the future,” said Terence Barnes, a decorator who has lived in New Caledonia for 20 years.

Experts had warned Macron against accelerating the legal change, but he chose to act before New Caledonia’s provincial elections, due this year, according to people familiar with the matter, who did not want to be named as the discussions were private. That was in keeping with a strategy of moving fast on tricky political issues, which yielded some success in reforming pensions last year, the people said.

The French president has stood firm on New Caledonia before. In 2021, he ignored calls by Kanak to delay a third and final independence referendum promised by past peace accords, to allow them time to mourn community members who died during the pandemic. The ballot was boycotted and loyalists secured a resounding victory.

For many, that sowed the seeds for current unrest, and Paris is offering few solutions.

The problem is not simply one of more financial aid. France’s previous attempts to narrow inequalities through large fiscal transfers to majority-Kanak areas of the island have had a poor track record. Unintended consequences have included inefficient white elephant projects and inflated salaries for some.

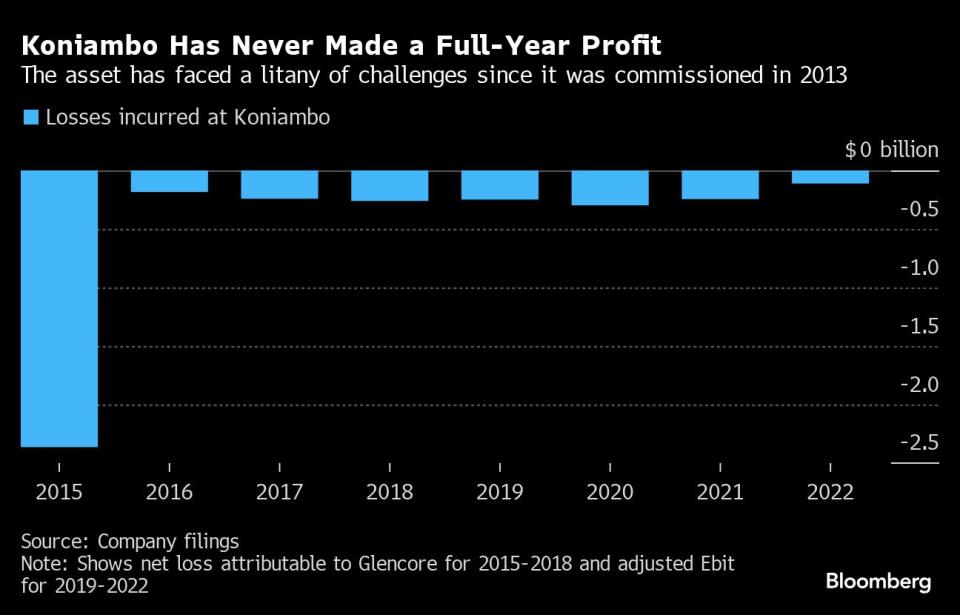

An emblematic project was the construction of the Koniambo nickel plant, as part of a joint venture between the largely Kanak Northern Province and a series of private companies.

A 7-billion-euro smelter was built with the aim of capturing more value from the islands’ ore riches while delivering high paying jobs to Kanaks. Today, it’s at risk of shutting down for good after its latest private backer, miner Glencore Plc, announced plans to pull out following a plunge in nickel prices. New Caledonia’s other two plants in the south of the island face similar fates.

Meanwhile, roughly a third of Kanak live in poverty, compared to just 9% of the rest of the population.

“The inequalities are very evident now with the young, in Nouméa particularly,’’ said Kakue, the entrepreneur. “When new accords are being negotiated, we must have the youth at the table.”

Almost half of the Kanak have no high-school diploma, whereas only 8% of White Europeans are in the same predicament, says Mathias Chauchat, a professor of public law at the University of New Caledonia. One in five Kanak is unemployed, compared to closer to one in eight for the overall population on average.

And it was the arrival of impoverished, disillusioned youth at demonstrations organized by New Caledonia’s pro-independence separatist group, the Coordination Cell for Field Actions or CCAT, that helped feed the subsequent unrest. “They attacked, outside of any political instructions, all the symbols of wealth from which they are excluded,” Chauchat said.

The disparities — themselves in part a legacy of colonial-era discrimination — have long fueled pro-independence sentiment among Kanak. They have been worsened by the pandemic and food inflation in a country where much is imported and already painfully expensive.

“The poor in urban areas suffered a loss of their purchasing power,” said Joël Kasarherou, an independent local politician. “It becomes a two-speed society.”

As Paris seeks ways to return calm to the archipelago, economic difficulties are set to endure long after the riots stop, weighed down by the costs of reconstruction. Among both Europeans and Kanaks, many have lost everything over the space of several weeks.

Few believe in a swift resolution.

“It’s about strategic interest. France wants to be present in the Pacific,” said Wamytan, the pro-independence leader. “And that means being in French Polynesia. It means being in New Caledonia.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Disney Is Banking On Sequels to Help Get Pixar Back on Track

The Budget Geeks Who Helped Solve an American Economic Puzzle

Israel Seeks Underground Secrets by Tracking Cosmic Particles

How Rage, Boredom and WallStreetBets Created a New Generation of Young American Traders

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.