Some pardon applicants in NC wait years on Gov. Cooper. Experts point to broken system.

North Carolina’s slow-moving and secretive pardon process needs to be reformed, an exoneree and advocates for people seeking pardons say.

That process allows people who’ve spent time in prison to clear their names officially and sometimes to get compensation.

As he nears the end of his second term, Gov. Roy Cooper has approved 10 commutations and 17 pardons in total, a spokesperson said.

Two of Cooper’s leading staffers declined to answer many of The Charlotte Observer’s questions about the process in an interview last week.

That secrecy is typical, experts say.

Here's our latest accountability reporting

Reality Check reflects the Charlotte Observer’s commitment to holding those in power accountable. Here are three of our stories from this week:

→ Fate of damaged Charlotte house where shootout killed four officers remains murky

→ CMS wants rules if NC private schools get new voucher money

→ Huntersville wants people to pay by the hour if records requests take too long. Is it legal?

“While the Governor has done a better job in his second term exercising his clemency power and granting pardons and commutations, the process remains opaque and leaves those seeking clemency wondering, sometimes for years, whether they will ever receive a decision,” Duke Law Professor Jamie Lau, who supervises the school’s Wrongful Convictions Clinic, said in an email.

Lau and another expert said that the problem is severe enough that there needs to be another process for people seeking pardons to get them, perhaps through the courts.

Advocates: System can be slow, secretive, political

The pardon process can start with a petition, where someone who was incarcerated makes their case for the state to forgive them, apologize for a wrongful conviction or lessen a sentence.

For weeks, the Observer asked Cooper’s office to share the number of pending pardon petitions, as well as the date of the oldest petition. They declined that request.

“We can’t talk about specific cases or specific numbers,” said Julia White, Cooper’s senior adviser, in an interview last week.

She added that it helps to maintain “the maximum amount of flexibility.”

The governor’s Clemency Office — which has four employees — and his Office of General Counsel review petitions and the cases they stem from. The governor can issue a pardon of innocence, a pardon of forgiveness or commute a sentence. General Counsel Eric Fletcher said officials reviewing the requests gather information from the applicants, victims and family, community members and court and prison records.

But lawyers who file those petitions regularly say they don’t know what will satisfy the Clemency Office, and that their clients can go years without an answer.

“There’s no procedure, so there’s no due process,” said Mark Rabil, a Wake Forest University Law professor who directs the school’s Innocence and Justice Clinic.

And the system is political, another longtime advocate for exonerees said.

“It seems like the only time pardons are addressed is when there is… somebody camping out in front of the Governor’s Mansion,” said Chris Mumma, the executive director of the North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence, a nonprofit. “Pardons have become political tools rather than tools for justice.”

Cooper, a Democrat, in 2023 pardoned four people after protesters picketed outside the Governor’s Mansion.

Mumma is a former Republican candidate for North Carolina attorney general.

Last year the Observer reported on the wait her client, Mark Carver, has dealt with since asking for a pardon of innocence in 2022 for a murder he never committed, according to the courts.

White and Fletcher in the governor’s office declined to discuss his case.

Man has waited nine years for an answer

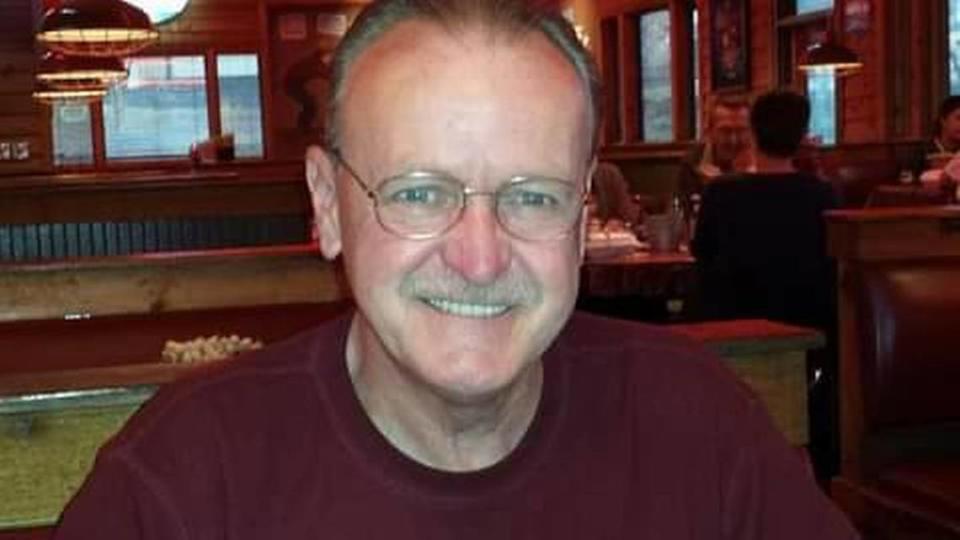

Michael Parker was incarcerated for 22 years after being convicted of eight counts of first-degree sex offenses and four counts of taking indecent liberties with children — his own children.

His 1994 trial in Henderson County was unusual.

The charges stemmed from a “commonplace domestic dispute” with his then-wife, Sandra, and turned into something very different, the court record that would ultimately free Parker says.

At trial, the couple’s children told stories of “costumed adults intoning incantations around fires while drinking the blood of their victims,” court records say.

He was one of the “earliest victims” of a wave of nonexistent ritual abuse claims, his 2015 petition for a pardon of innocence says.

One of his children recanted her testimony in 2010, and said that she had lied. Her parents had separated, she had just turned eight and she wanted to make sure her father stayed in jail to protect her mother, she said.

Judge Marvin Pope vacated Parker’s conviction in 2014, cleared his charges and let him out.

Parker lives in South Carolina now and has started to rebuild a relationship with his kids, he said. He is still waiting for Cooper to answer his 2015 petition for a pardon of innocence.

“(A judge) concluded that if I were tried today, I would be acquitted,” Parker said, adding that he can’t understand why Cooper is “stonewalling.”

Parker said he has received no updates in the last nine years.

White and Fletcher declined to comment on Parker’s petition.

Alternatives

“I have long advocated for greater transparency in the process, and for there to be an alternative mechanism through the courts for people like Michael to have their innocence recognized and be compensated,” Lau, who has helped Parker in his quest for clemency, said in an email.

He still thinks the General Assembly should pass legislation to provide an option through the courts to have innocence recognized, something they tried to do with House Bill 877 in 2021. That bill failed after the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys came out against it, Lau said.

Rabil seconded the idea of giving the courts a way to grant pardons.

“I’ve never been a politician, never will be,” he said. “But I can see that it’s hard for politicians to make decisions in cases where people might criticize them, especially if they’re running for another office.”

Judges are also elected, but have more independence, he said.

In April 2021 Cooper signed an executive order that created the Juvenile Sentence Review Board, a board to review cases where people were convicted and sentenced for crimes as adolescents.

“This Review Board’s mandate is to promote sentencing outcomes that consider the fundamental differences between juveniles and adults and address the structural impact of racial bias while maintaining public safety,” part of the executive order reads.

Rabil said he’s dealt with both the Governor’s Clemency Office and the juvenile review board, and there is a difference. One works better than the other, and that’s because there are specific expectations from the latter.

He knows what the review board wants when sending in paperwork for his clients: Re-entry arrangements, explanations of any prison infractions, certificates of programs taken while they’ve been locked up.

He’s still confused about what exactly the Clemency Office wants, though.

NC Reality Check reflects the Charlotte Observer’s commitment to holding those in power to account, shining a light on public issues that affect our local readers and illuminating the stories that set the Charlotte area and North Carolina apart. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email realitycheck@charlotteobserver.com