Pierre Poilievre returns to his old university club, where 22 years ago he feuded with Patrick Brown

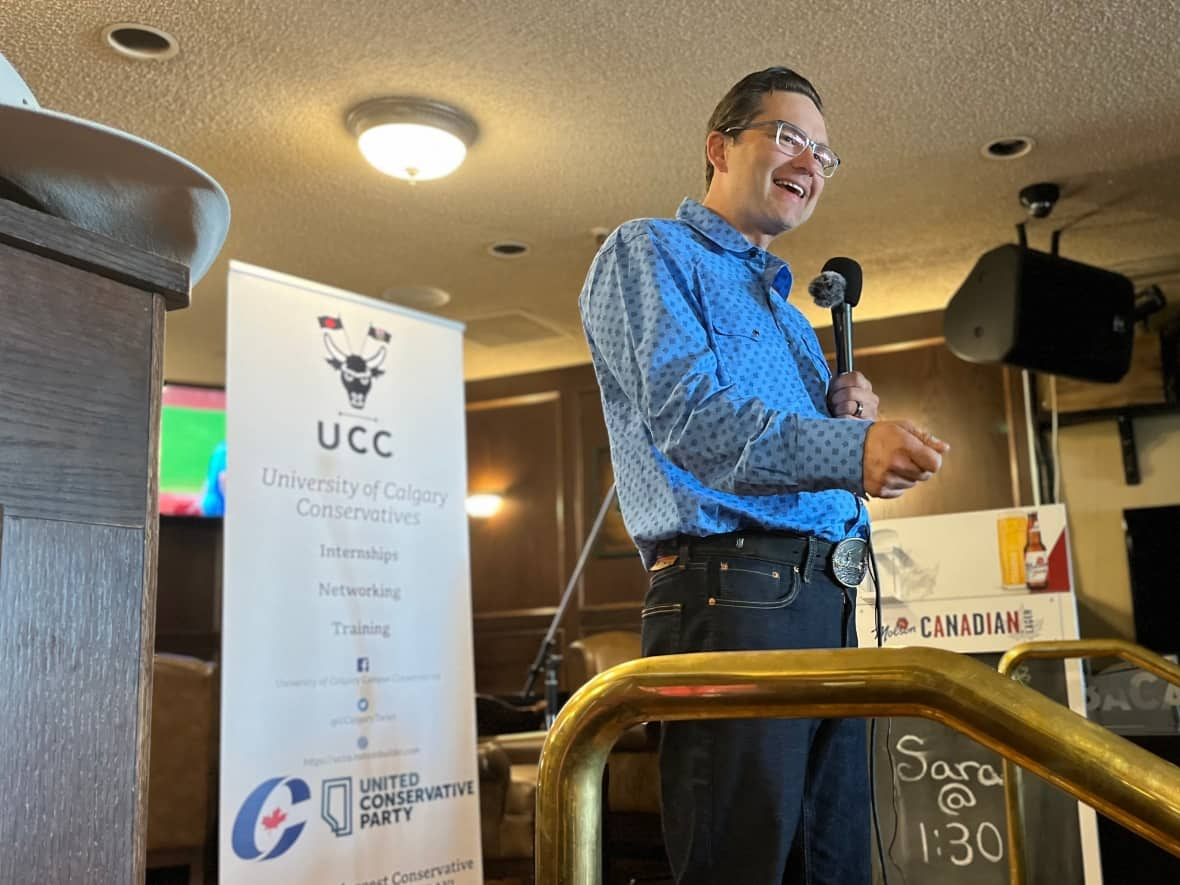

Clad in cowboy hats and plaid, dozens of young conservatives gathered at an Irish pub in Calgary early Sunday afternoon, sipping water and draught beer while waiting for Conservative leadership hopeful Pierre Poilievre to arrive.

Poilievre's political roots trace back to this club — the University of Calgary's conservative club. And much of his points of view (and even one current feud) echo back those 22 years.

"I don't think you can understand Pierre Poilievre without understanding his background," said Mount Royal University political scientist Duane Bratt. "You have to look at growing up in Calgary, going to the University of Calgary, taking political science in the time period that he did."

Poilievre, now 43, was greeted to the pub by attendees jubilantly ringing cowbells. Earlier that weekend, he had reportedly skipped a downtown Conservative leadership debate hosted by online news and opinion website The Western Standard in favour of a fundraiser hosted by Calgary entrepreneur W. Brett Wilson. On Saturday, he attended the Conservatives' 1,400-person Stampede barbecue.

And though members of the youth conservative club stressed they were not advocating for any single candidate, Poilievre's message on Sunday was received by loud cheers, just as it was at the barbecue.

"That's somebody who's walked through our shoes, walked the same halls that we've gone through," said Brody Wyatt, 21, a senior advisor with the club.

The Calgary-born Poilievre studied international relations during his time at the university. In 1999, he was one of 10 finalists in an "As Prime Minister …" essay contest as he argued for, much as he does today, "leaving people to cultivate their own personal prosperity and to govern their own affairs as directly as possible."

"I just hope that none of my views are offensive to the prime minister because many of them come into conflict with the outdated system he has run for the past few years," Poilievre told the Calgary Herald in 1999.

Lanny Westersund, who was vice-president of the club at the time, recalls travelling with Poilievre across the backroads of the province to fundraise "hat in hand" with constituencies, so students could participate in political conferences.

The political club's office at the time was next to an area of the university called Speaker's Corner, where students and others would gather to debate.

"Pierre was always an active and insightful debater. And Pierre and I were kind of on different sides of the party," Westersund said, with Poilievre having purchased a membership in the Reform party around that time.

"I came up through the Tory side. So it always led to spirited debates."

'Eliminate' the anti-Clark element

At that time, Poilievre's political viewpoints were shaped in large part, Westersund said, by those in the Calgary university's political science wing — including former Alberta cabinet minister Ted Morton, one of the authors of the famous "Firewall Letter," and writer Rainer Knopff.

Knopff and Morton are two of the four members of the so-called Calgary School, a term popularized by Ralph Hedlin at the oft-controversial and now-defunct conservative Alberta Report magazine (Poilievre himself would write a column for the magazine for a short period). The Calgary School is often cited as being influential to the philosophy behind the Reform Party of Canada.

But divides within conservative ideology led to a public split between Poilievre and a young Patrick Brown — described as a "diehard Jean Charest supporter" in an Ottawa Citizen article from the time — who was then president of the national youth Tory body.

In a 1999 article from the Calgary Herald, Poilievre, then the president of the young Tories on the University of Calgary campus, threatened to move the Progressive Conservative club to the Reform-inspired United Alternative.

He cited a possible purge of anti-Joe Clark young people from campus clubs. Clark was leader of the Progressive Conservative party at the time.

"The direction of the party just seems to be downward," Poilievre is quoted as saying, slamming Clark as "anti-youth."

In addition to his role as president of the national Progressive Conservative youth wing, the more centrist Brown was also executive of the Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario. He was hailed by former Conservative senator Hugh Segal in a 2015 Ottawa Citizen article as the hardest worker he had ever seen.

"He brought a level of professionalism, determination and intensity to his work, which I thought represented exactly the kind of energy mix that the [Ontario] Progressive Conservative party — frankly, any party — would benefit from," Segal told the Citizen.

But in a leaked memo obtained by media at the time, Brown was noted as discussing plans to "eliminate the anti-Clark element from the youth wing, most specifically those in leadership positions."

Brown denied he had any plans to purge Poilievre, who had referred to Clark as a failed leader with a record of attacking young people, from the regional club. The U of C club would later back down from their threats, with Westersund telling the Herald the club had no plans to fight with the federal Progressive Conservatives.

A combative style

Poilievre's dust-up with Brown was hardly his first rodeo. Some on campus found the methods of Poilievre's associates to be extreme. In a Calgary Herald article from 1998, while Poilievre was vice-president of the university's Reform club, the students' union president accused the club of practising "legal terrorism."

The students' union had decided to suspend the club's ability to have office space in student facilities, book rooms or receive grants after receiving allegations of the club hanging banners in unauthorized spaces, placing Reform stickers in unauthorized locations and "abuse of students' union staff."

Poilievre referenced the incident as part of his speech on Sunday, claiming the "far-left" president had banned the club because "we left a window open over at the clubs room."

WATCH | In 1998, then-MP Jason Kenney arrived at the university to show support for the Reform Club. At 0:16, a young Pierre Poilievre is pictured:

At the time, the students' union president said similar administrative issues had cropped up among the other 146 student clubs on campus, but the Reformers took the complaints "far too seriously," announcing it would take the complaints to the Court of Queen's Bench to protest the decision.

"This is not the first time [the Reform club members] have held people hostage with lawsuits," president Paul Galbraith told the Calgary Herald at the time.

The Reform club's president, Ben Perrin, accused the union of acting in a biased manner and said the club was "taking a stand for freedom."

"We are not the first club that the [students' union] has bullied, but we are the first to stand up and say no," Poilievre is quoted to have said.

Round 2

His time with the university campus conservative club in the rear-view mirror, Poilievre would go on to found a political communications company with former Alberta justice minister Jonathan Denis before entering politics himself, working on a leadership campaign for eventual Canadian Alliance leader Stockwell Day.

"Love him or not, I'm the guy who people can either blame or thank for bringing him to Ottawa," Day said in a phone call.

Poilievre has stayed in politics. He won election as a member of Parliament in 2004 and has remained in the House of Commons since. Brown would join him in Parliament two years later, although he is now the mayor of Brampton, Ont.

That initial feud may have died down, but 22 years later, Poilievre and Brown — considered for much of the federal Conservative leadership campaign to be its front-runners, along with Charest — are embroiled in another spat that goes beyond traditional politicking.

Brown was ejected from the leadership race last week over allegations he broke financing rules. However, he claims members of the Conservative Party establishment and supporters of Poilievre worked to disqualify him from the race. Poilievre's campaign disputes that claim.

Poilievre's background and education set the stage for the candidate he is today, said Bratt, the political scientist at Mount Royal University, and is unlikely to change even should he secure the nomination.

"I don't think he can make a pivot, because this is who he is," Bratt said. "This is who Poilievre was when he was in Harper's cabinet, this is who Poilievre was when he was in university, this is who Poilievre is now. There will be no pivot for Pierre Poilievre."

After his speech, flanked by pool tables and Wimbledon TV highlights as Toby Keith played on the sound system, Poilievre spoke with young members of the conservative club. "Don't give up," he told them, before grabbing his cowboy hat and bidding them farewell.