The privacy implications of DNA testing kits that can 'alter your life'

More than a few Canadians are now awaiting results of DNA testing kits they received as Christmas gifts, but many remain blissfully unaware of the privacy implications or the possibilities that flow from such a test.

When Pam Carpenter Amero of Medicine Hat, Alta., took a test through online company AncestryDNA, she wanted to learn "how Scottish I am." She was surprised when the results showed she's 42 per cent Irish, but that was hardly the biggest discovery.

She was shocked to learn she had a half-sister living in Nova Scotia.

"I never in a million years expected to find a sibling," she said. "I even commented to my husband that I didn't expect to have any long-lost relatives coming out of the woodwork."

Finding half siblings can be just one of the surprises that comes from DNA testing, an increasingly popular way for people to learn about their ethnic backgrounds.

DNA testing is now as simple as spitting into a vial or swabbing your cheek, depending on the company you choose to do the test. Then you ship it off for analysis and await the results.

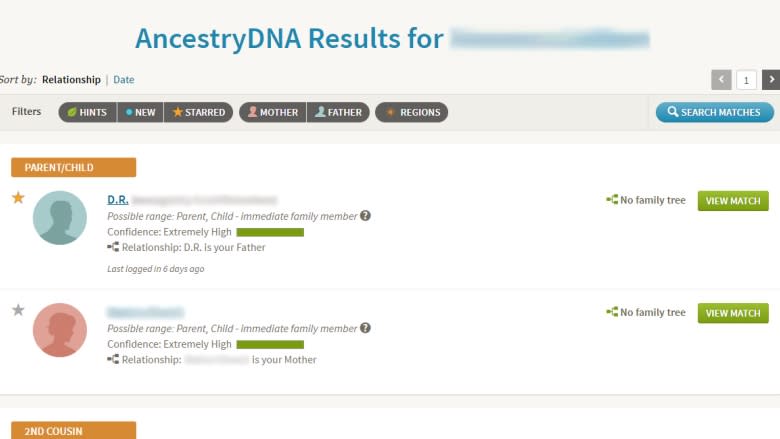

Once your results are in, most testing companies show genetic matches — everyone from parents and siblings to distant cousins — who have tested with the company. Many also provide a way of contacting them.

While Carpenter Amero had no privacy concerns about doing a DNA test, Halifax privacy lawyer David Fraser says not everyone is aware of the possible fallout.

"Do you want to use this information to be matched to somebody who might be a relative of yours? Think long and hard about that. That's a pretty significant decision," Fraser said.

Several DNA testing companies warn users that results could provide unexpected or unwelcome information, and not just surprises about ethnicity and unknown siblings. For instance, some people learn their father is not their biological parent.

"You may learn information about yourself that you did not anticipate," warns 23andMe, a testing company. "This information may evoke strong emotions and has the potential to alter your life and worldview."

The tests are nonetheless popular. Ancestry, for instance, reported sales of 1.7 million kits during the 2017 Black Friday weekend, and the company says it has six million people in its DNA database.

But not everyone considers the implications of DNA testing, Fraser said, even though "this is some of the most sensitive information that exists."

"It has become one of those things that is almost as casual, or potentially as casual, as other things we do on the internet," Fraser said. "A huge number of people just kind of click 'I Agree' and they continue."

Fraser said users need to do their homework and shop around to ensure they are getting the right test for the kind of information they are seeking and the right privacy protections.

"If you're looking for health information, go to a health-related site. If you're looking for family, go to a family related site. But also be careful what you sign up for because there may be other things that are in the terms of use."

'Scrutinize each company's website'

Fraser points out people who test have options in terms of their information and what is made public.

In most cases, your matches will see you and how you're related, unless you change privacy settings to lock down the information. The problem, Fraser said, is people tend to accept the default privacy settings in services that they use.

In December, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission issued a statement about DNA testing and the privacy implications, suggesting potential customers should comparison shop.

"Scrutinize each company's website for details about what they do with your personal data," it said. It suggested people not use defaults, but select the most private options and then revisit their choices once they're more familiar with the site.

It also urged users to recognize the risks, saying "hacks happen."

"You have the right to be foolish, you have the right to make bad decisions, but they really should be informed decisions and so people should take the time to read the terms of use of these sites and their privacy policies," Fraser said.

That in itself can be a challenge. Each testing company has its own terms and conditions, privacy and cookie policies that can range from 15 to 45 pages.

Fraser said you should look at a privacy policy to determine to what extent a company shares your information with other people and how long they hold on to the information. If you want to close your account does that result in its ultimate deletion, do they keep the samples? Will they use your DNA for research? What happens if you die?

For instance, 23andMe says if you use a third-party site like Facebook or Twitter to sign into your DNA account, it will collect information such as your profile picture, age range, and friends or followers, depending the privacy settings.

Fraser said when it comes to companies like 23andMe that test for health risks like Parkinson's disease and whether you're a carrier for certain genetic conditions like cystic fibrosis, people should be especially careful.

He pointed out that it's not just your personal information, it's information about your parents and your offspring, so there are other people implicated.

23andMe, like other DNA testing companies, warns potential users that genetic information you share with others could be used against your interests. For instance, if you share your genetic information with a doctor, it may become part of your medical record and then be accessible by insurance companies.

Canadians, however, are protected by the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act, which makes it illegal for insurers or employers to request DNA testing or results.

Retired senator Jim Cowan of Halifax, who shepherded the bill through the Senate and fought for three years to see it passed, told CBC News that genetic testing is "the way of the future" because it allows doctors to personalize medicine to an individual.

However, he maintains that information should remain private.

"You shouldn't be forced to share [genetic information] with anybody against your will or without your consent," he said.

Canadians who purchase DNA kits in other countries are not covered by Canadian law but the law of the country in which they're living.