‘A public disgrace’: The forgotten desecration of bodies at Kansas City Union Cemetery

Without a plaque, without a statue, without a single monument or gravestone, it can become all too easy to forget a city’s successes, let alone the shames it may wish to avoid.

In the shadow of downtown, at Kansas City’s Historic Union Cemetery, evidence suggests a mass desecration of graves there that, 100 years later, few know about and no one has yet to reconcile.

The ugly details — of children hoisting skulls on sticks, of bodies of untold numbers of Black and white paupers being dumped three or more to a grave, of earth-moving machines plowing up their bones like fieldstones — are not told on tours. Nor does a single paragraph of a 228-page book on the graveyard, published in 2014 by The Star, make any mention of them.

On a recent rainy morning, Heather Faries, the 34-year-old vice president of the Union Cemetery Historical Society, stepped from the sexton’s cottage — the office of the caretaker at the cemetery’s entrance, 227 E. 28th Terrace. She walked north away from the gravestones and obelisks of the esteemed dead, pioneers buried in the city’s oldest public cemetery: John Calvin McCoy, founder of Westport; Alexander Majors, a creator of the Pony Express; famed artist George Caleb Bingham.

She stepped from a puddled path up a gentle rise, a grassy expanse that — despite an estimated 55,000 bodies having been buried at the tiny cemetery since 1857 — sits empty of grave markers, although not of graves.

“Where we’re walking now,” Faries said, “this is all potter’s field.”

It’s where, over the cemetery’s first 60 years, thousands of men, women and children — having died unknown, or destitute — were buried and then, in time, heaped atop one another, two deep, three deep and, by one account, 12 deep into the skeletal remains in existing graves.

“Who knows how many people are under us right now?” Faries said.

That was not the only outrage at hand.

“Over there,” Faries said, “was the Black part of the cemetery.”

She first pointed to the area northeast and then beyond to the fence line where cars sped up McGee Trafficway, south of what’s now Crown Center and Hallmark Cards.

“The story that’s been handed down,” she said, “is that whenever McGee went in, and they sold off this part of the cemetery, they said no one was buried there. But when they started doing work, they were digging up bodies. They didn’t care. They just filled the trucks full of dirt, bones, whatever. They dug them up and dumped them in the (Missouri) river.

“That’s the story I’ve been told. I haven’t seen actual, paper proof. But that’s what’s kind of been passed down.”

The narrative has been shared for so long, that even with its murky and uncertain details it has become nearly mythic among the volunteers at the Historical Society, a nonprofit formed in 1984 to preserve the cemetery’s history and records and, with the Kansas City Parks Department, to care for its grounds.

Kevin Fewell, a president of the society for a decade before his recent retirement, shared the story for years — not just about how the graves of Black people were purportedly unearthed for McGee Trafficway on the northeast, but also how the bones of paupers were pried from the earth on the northwest to make way for Warwick Trafficway.

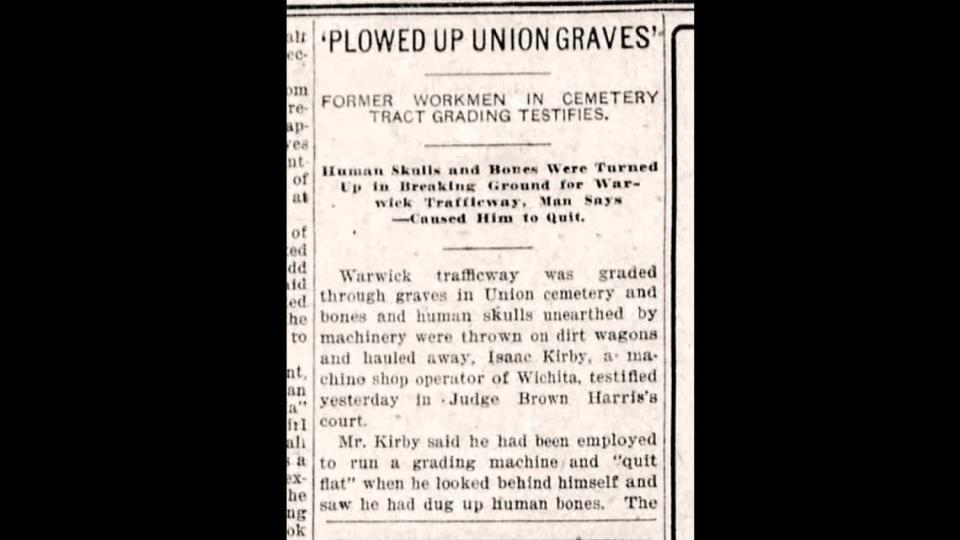

“There’s actually newspaper articles from the time that the road was built. There was a lawsuit,” Fewell said from his new home in Florida. “All that was documented.” At least to a degree.

Before moving, Fewell had lived since 1994 in the Union Hill neighborhood bordering the cemetery. The story of the graves, he said, so disturbed him, “I could probably count on both hands the number of times I drove on McGee Trafficway.”

“Because it’s just ghosts, you know?” Fewell explained. “Just the sense of who those people were, and the loss. I don’t think you could find anybody who would think it was right. … It’s still a story to be told.”

Carter Enyeart, a member of the historical society for 15 years, just wants to know what’s true. “Whatever happened,” he said, “we have to acknowledge and accept it. This has been on my mind for years, this story.”

It’s been on Kara McKeever’s mind, too. New to the board last year, she began volunteering in 2020, searching records to help identify the location of people buried in the potter’s field.

“I spend a lot of time thinking about the people that you cannot see,” she said. “We make a lot of fuss about the founders being there. And that’s important. They have the big stones, the stories. But there are so many people buried there who we don’t know a lot about. And they’re right there. And that’s a big part of our history.”

The story Fewell told of remains being heaved from the earth, possibly tossed away, only deepened McKeever’s commitment.

“I strongly believe,” she said, “we need to do a better job of reckoning with the darker side of Union’s history — which starts with knowing it.”

As Faries said, “I mean, with any part of history, there’s darker parts, and there are sad parts, and there are parts that make us ashamed. But it’s part of our history, and it should be known.”

If knowing is possible.

‘Shocking’ burials

In the case of Union Cemetery, a dive into records from the State Historical Society of Missouri, academic histories, and news accounts from The Star, The Kansas City Times and The Kansas City Journal reveals an early history that was, in turns, calm and filled with conflict.

From its founding in 1857 and into the early 1870s, the 49-acre cemetery had reporters waxing poetic.

“’Tis pleasantest to visit the ‘City of the Dead’ in autumn,” wrote one reporter in 1873 for a Sunday front page story in The Kansas City Times as he “rambled through the sylvian shades” of the graveyard. “There seems to be something so appropriate and kindred-like between the season and the place as the soft, still breeze creeps gently through the trees, scattering the seared and yellow leaves like a yellow pall over the dying verdure of the year.”

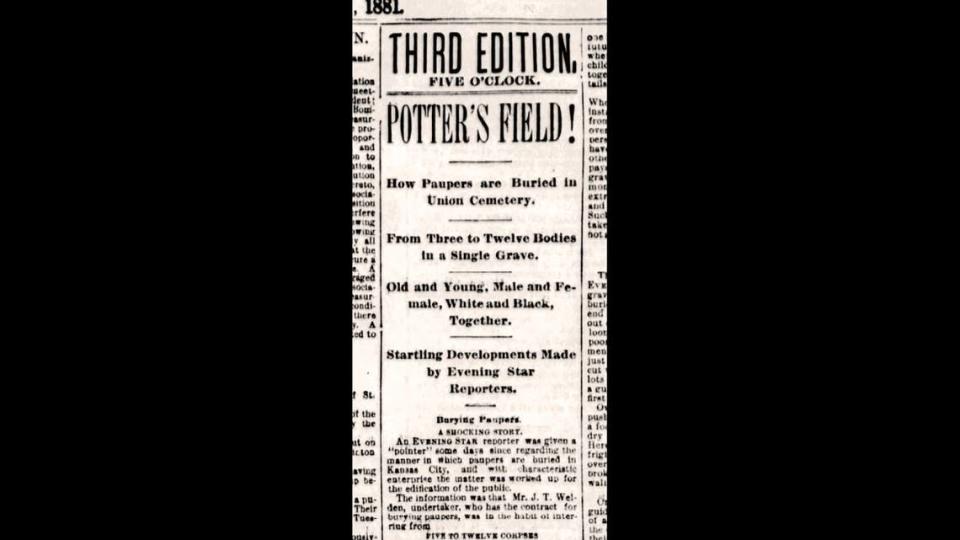

Eight years later, in December 1881, Star readers had a more startling headline delivered to their doors:

“POTTER’S FIELD! How Paupers are Buried In Union Cemetery. From Three to Twelve Bodies in a Single Grave. Old and Young, Male and Female, White and Black, Together.”

An undertaker, J.T. Welden, who had contracted with the city to bury paupers for $2.60 each, was the story’s prime source.

“The shocking manner in which the bodies of the dead are handled is graphically portrayed (by Welden),” the reporter wrote. “He says the custom is to dig a hole from 13 to 14 feet deep and place as many bodies as it is possible to crowd into the narrow space. They are not all put in together, but two or more are taken out at one load and are placed in the hole to await future consignments.

“It matters not whether the bodies (are) black or white, child or adults, male or female. All go in together, the grown persons, head and tails like sardines in a box. … The city pays $1.20 each for the graves, and if one grave answers the purpose of twelve it is money saved on the contract. … Such a scheme is profitable to the undertaker and the sexton alike, so long as it is not generally known.”

For the next 50 years, the cemetery would face repeated criticism and, finally, lawsuits with allegations of corporate greed, fraud and the desecration of the dead, including when land was graded and hauled away for construction.

”The poet Longfellow refers to the burial ground as God’s-Acre, implying that all concerning it should be peaceful and revered,” M. Joan Huse, then a student at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, wrote in a 1983 academic history kept by the Historical Society. “The history of Kansas City’s Union Cemetery does not reflect this peace and reverence.”

In the broadest sense Union Cemetery was borne from turmoil, dating to the years when what’s now Kansas City was two separate and growing communities — the Town of Kansas along the Missouri River, and the larger and more hectic merchant town of Westport, five miles south, on the Santa Fe Trail. In those early days, the dead were buried on family lands, in church plots or in the few city cemeteries.

But in 1849, when 300 pioneers disembarked on the riverfront from New Orleans, their steamboat carried more than their belongings. It brought cholera, which killed half the settlers, plagued the area, and, over time, stressed the capacity of existing graveyards.

City leaders knew that a new, larger burial ground would be needed for a growing city. James Hunter, a farmer and Westport merchant, stepped up, offering to sell 49 acres of his farmland to be used in cooperation — in “union” — as a public cemetery midway between Westport and the Town of Kansas.

So Union Cemetery, in 1857, came to be — a rolling acreage, two squares of land, bounded by Main and Oak streets, 27th and 30th streets.

Hardly a nonprofit, the cemetery was created as a money-making business, incorporated by the Missouri General Assembly as the Union Cemetery Association. The six original shareholders were prominent businessmen, including Hunter, and Milton J. Payne, who, besides being a wealthy landowner, also happened to be Kansas City’s mayor in his third one-year term.

Just 5-foot-3, Payne would serve six terms and be credited with doing great things for an ambitious, young city, such as covering roads with gravel, creating planked sidewalks, building the first police station, setting up the city for sewer and water systems.

Kansas City was tiny, its population about 4,000, when he and his partners opened the graveyard. They mistakenly thought the grounds would be big enough to serve the city’s needs forever. But by the time Payne died at age 70, in the year 1900, the city’s population had exploded to 164,000.

Body count

No one even now knows how many bodies are buried at the cemetery.

In 1889, a fire consumed the sexton’s wood cottage, sending the cemetery’s first 30 years of burial records up in flames. By then, the remains of 50,000 people, equating to an impossibly cramped 1,000 per acre, were already estimated to be interred there: city scions and vagabonds, heroes and criminals, mothers, children, laborers, Union and Confederate soldiers, awardees of the Medal of Honor.

Death notices in the daily papers offered glimpses into Kansas Citians’ lives and last moments:

▪ July 18, 1902: “The funeral of Lee Anderson, the 4-year-old son of P.H. Anderson who was run over and killed by a wagon last night at Fifth and Cherry streets will be held Saturday afternoon at 2 o’clock from the home, 607 East Fifth Street. The burial will be in Union Cemetery.”

▪ Dec. 8, 1903: “HOYT — Benjamin, of 2006 Locust street, 73 years of age, died yesterday morning of senility.”

Some merited larger headlines:

▪ April 1, 1901: “Florian Irmer, 40 years old, despondent and demented with drink, ended his life Saturday night in Union cemetery by hanging himself to a cedar tree at the side of the grave of his wife, Pauline Irmer, who died eight months ago yesterday. It was the third attempt at suicide. He leaves three small children without means of support and with scarcely a relative in the world.”

▪ May 23, 1904: “The funeral of Gaw Lung Foy, the rich Chinese merchant who died last week, was held yesterday afternoon from 309 West Fifth street, attracted a large crowd of spectators … between 1,500 and 2,000 persons gathered to see the burial rites. … A band led the procession and the last carriage was filled with Chinese musicians, beating tom-toms and playing other Oriental music on weird looking instruments.”

▪ Sept. 7, 1904: “John Harmon, the 3-week-old son of Mrs. Uinta Harmon, the woman who was sent to the city hospital last week by the Humane officer, died yesterday afternoon. The records at the hospital give inanition as the cause of death. The child’s mother came to this city from Leavenworth and asked Colonel J. W. Greenman, the Humane officer, to find a home for her baby. She said she wished to find employment. The police surgeon who made an examination of the baby said it was ill from lack of nourishment.”

Then there were the paupers — white and Black — buried in untold numbers and in uncertain spots in the potter’s field to the north. Over time, their cheap pine boxes and wood grave markers would rot, disappear and not be replaced. The sexton recorded their names, their date of burial. But without markers, knowing their exact location in the field became anyone’s guess.

Black people, meanwhile, were allotted plots to the east and north in the segregated cemetery, even as paying families.

What no one surely expected when their loved one’s bodies were laid to rest is that one day some of their bones would end up in the unlikeliest of places: a courtroom.

Of corpses and commerce

The headline in the The Star that Tuesday — front page, first column — was printed in capital letters: “THE SHAME OF A CEMETERY.”

The date: March 28, 1911.

“A cemetery’s shame was bared in court this morning,” the story read, “when H.S. Conrad, counselor for the city, introduced as evidence of the unsanitary condition of the Union burying ground, a sackful of bones — those of men, women, children, picked up at random in a walk through the cemetery.”

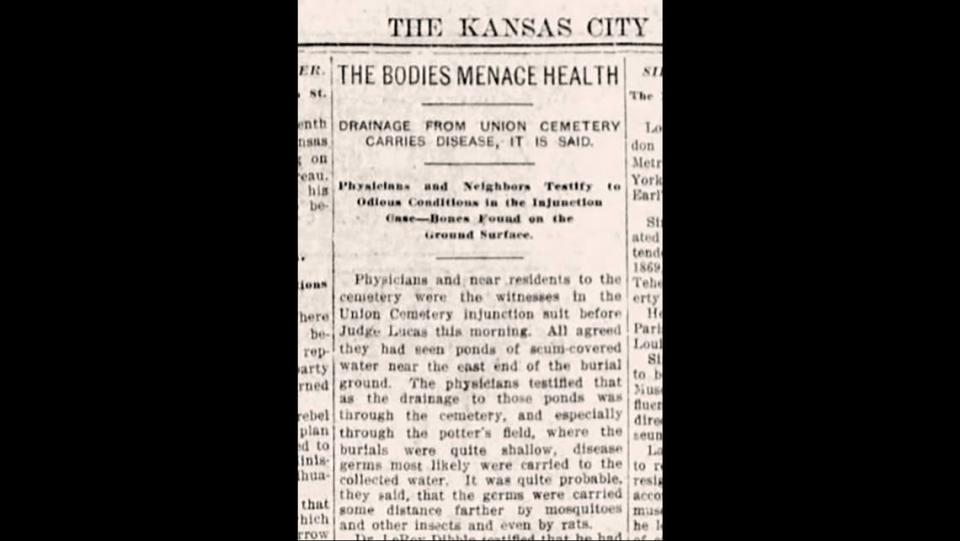

Besides the clattering bag, Conrad brought pieces of broken coffins and showed a dozen photographs taken one day prior of stagnant water, thick brush, uncut weeds and toppled headstones. The manager of the cemetery testified that he did not think the cemetery unsanitary, but was then asked about potter’s field.

“While I have been in charge of the cemetery, we have buried over the potter’s field only once,” the manager said.

“Yes, but in digging graves in the field,” Conrad asked, “you frequently run into bones and remnants of boxes, don’t you?”

“We have,” the manager conceded, “but we always gather the bones up, bury them again, and then put the new box down on top of them.”

It appeared as the if the ghoulish practices discovered in the 1880s had not stopped. Except this time, unlike 30 years prior, the fate of the cemetery was on trial. It was a hearing before a judge on whether to shut down Union’s burials, an existential threat to its business and shareholder profits. What was made clear publicly is that the issue was not just about corpses, but about commerce.

In 1910, Kansas City was a city on the move, growing fast and growing south. A new Union Station, to open in 1914, was already under construction. City political leaders, intent on building better roads — particularly as alternates to the steep climb that was then Main Street — had no qualms about declaring what and who they thought was standing in the way: Union Cemetery and its shareholders — with F.G. Payne and other children of the former mayor among them.

“It is the most narrow and obstructive institution the city has to contend with,” a city counselor complained.

The cemetery was created in what was then the hinterlands. Now it was a valuable piece of major real estate standing in the center of a city that had grown around it. It did not help that, for decades, the cemetery had rebuffed the city, refusing to pay taxes like other landholders, arguing its original charter made it tax-exempt, thus shifting the burden for road and other city improvements on neighboring homeowners and merchants.

In the summer of 1910, the city acted in two ways: It passed an ordinance shutting down all burials around the city’s center, meaning Union Cemetery. The headline was frank — “BLOCKS CITY’S ADVANCE.”

”When it was first opened to the public,” the piece said of the cemetery, “it was in the country — now it is retarding the city’s growth and blocking a possible easy grade traffic way to the South Side.”

The city’s other move: Through its right of eminent domain, it seized what it described as “unused” ground in the northeast corner of the cemetery to build a diagonal portion of a new McGee Trafficway to run along the cemetery’s east side.

The Cemetery Association fought back. But it would lose its appeal in December. By that time, the contract to start construction had been signed. But the court hearing to decide whether to shut down burials remained. Rather than argue that the cemetery was blocking progress, the city argued that it was an unscrupulous business and health menace.

Neighbors testified to the cemetery’s “unbearable” stench in the summer. A physician who toured the cemetery, “had been surprised, in the potter’s field, to find many humans bones on the surface of the ground.”

Shareholders were making 20% annual profits on their money. Yet there was no fund to maintain graves. All upkeep was borne by families.

“Some of the residents of that part of the city told me they had seen boys of the neighborhood parading with a skull stuck on top of a stick,” Councilman John F. Ward, who drafted the ordinance, would tell The Star.

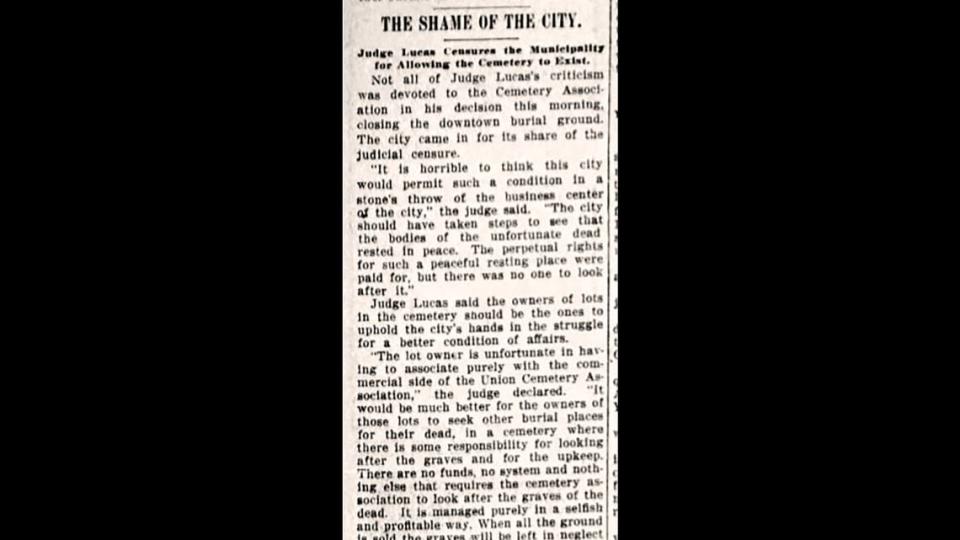

In April, when Judge O. A. Lucas ruled to uphold the ordinance and shut down burials, he pointed his outrage at more than the Cemetery Association.

“It is horrible to think this city would permit such a condition in a stone’s throw of the business center,” he said. “The city should have taken steps to see that the bodies of the unfortunate dead rested in peace.”

He told grieving families that they would do well to move their dead rather than keep them at Union.

“There are no funds,” Lucas said, “no system and nothing else that requires the cemetery association to look after the graves. It is managed purely in a selfish and profitable way. … No other such condition exists in any other cemetery in the city. … From some of the foreign countries we read reports from densely populated districts where the bones of the dead are dug up to make room for others. I never knew before of the existence of any such condition in our country.”

The ruling against the cemetery would not last.

The Missouri Supreme Court overturned it two years later, with Justice Arcelaus Marius Woodson concluding, in May 1913, that the ordinance was not about securing the public’s health, it was purely about business, “passed on the instigation of real estate agents, land owners and speculators who think this cemetery stands in the way.”

Eight months later, in January 1914, McGee Trafficway was finished.

There is no doubt, based on public reports, that the Union Cemetery Association treated the graveyard and the dead in its care, especially the poor dead, with miserable neglect for decades. After the city lost its case to shut down burials, it fought the cemetery to pay taxes and would finally win.

“There have been a lot of ugly displays of greed in Kansas City,” The Star’s editorial board opined in December 1913. “But the limit of indecency is reached by the Union Cemetery Association. It profits by improvements that it won’t contribute one cent to pay for. It capitalizes the virtues of the cemetery founders and perverts their virtuous purpose to a purpose of greed.”

Given the cemetery’s focus on money over morality, the story that the graves of poor people — or, in a particular, Black people — were uprooted to build McGee Trafficway seemed plausible.

But in searching at least 100 news stories, histories and sources from that time — from 1911, when the contract for McGee was awarded, to January 1914, when the contract was completed — no document was found to confirm that any graves on the northeast side were desecrated for the trafficway.

The other side of the cemetery, however, is a different matter.

Four skulls in a box

Isaac Kirby, 75, from Wichita was telling his tale. He was driving a road grader, building Warwick Trafficway in 1916 in what was then the northwest part of the cemetery, when he looked down and saw the bones.

“I couldn’t tell whether they were Indian, white or black,” he said, according to The Times. “I don’t know if they were of men or women.”

Once again the cemetery and its owners were in court. Kirby was on the witness stand in the packed courtroom of Judge Brown Harris. This time it was 14 years later, February 1927, for a hearing that would last 19 days. Instead of the city trying to hold the cemetery to account, it was 75 cemetery plot owners — the sons and daughters of some of Kansas City’s famed pioneers and others whose loved ones lay in the long-neglected graveyard.

Kirby, a witness against the cemetery, was being grilled by the cemetery’s attorney, who was attempting to impugn him.

“Do you remember whether you were discharged (fired) or whether you quit that job of your own will?” the attorney asked.

Kirby’s reply was heated, The Times reported. “I quit myself,” Kirby said. “I never had worked where I had to destroy graves and, you can let me tell you, I never will.”

The courtroom broke into applause. Judge Harris rapped his gavel for order. How did Kirby know that the bones were even human, the attorney continued.

“Well,” Kirby responded, “a colored woman came up to me and asked if I could tell her where the sexton was. She said (pointing to the ground), ‘I have a husband lying there and a daughter lying there. It’s a pity they can’t let the dead alone and the living live.’”

Nellie McGee Nelson, the daughter of Kansas City pioneer and wealthy merchant Allen B. H. McGee, later testified that, 20 years earlier, she stood alongside bereaved mothers, mourning their dead babies, at graves at 27th and Main streets. Now, both Warwick Trafficway and the White Motor Truck Co. sat there.

James I. White, who worked for Collier Brothers contractors, told the judge, “I operated a rock crusher in the potter’s field in 1901, and for about seven years after. We unearthed a lot of human bones about 200 feet south of the present Twenty-seventh street and about seventy-feet east of Main Street.”

Often, they were found less than 24 inches under the surface.

“The skeletons were uncovered by dynamite blasts in the quarry,” White said. “We found them in the dirt and, of course, they were not complete. I remember one blast unearthed four skulls and a number of other bones.”

The skulls, he said, were kept in an old coffee box in a tool shed, “but when the boys got to playing pranks with them, we took them to the edge of what is now Warwick Trafficway and buried them.”

A winding set of events brought them to court, beginning in 1922, when Howard E. Huselton, a former Star arts critic who became successful in real estate, attended the funeral of a friend at Union Cemetery. He was aghast at the conditions: sunken graves, weeds nine feet high, toppled gravestones all within sight of where a new Liberty Memorial was being planned.

He spoke out.

“This unkempt cemetery, with its broken tombstones and sunken holes, is a public disgrace,” he told a gathering of the real estate board and South Side Improvement Association. “While we are on the verge of erecting a great Liberty Memorial to the boys who died in France, nearby, eight hundred out of one thousand graves of Civil War veterans lie unmarked.”

His speech sparked news stories and a movement, emboldening families of the dead to organize in a years-long effort to get the Kansas City Parks board to take over the cemetery. That movement, in turn, led to the revelation that since 1916, the Union Cemetery Association had done nearly nothing to maintain the cemetery, but they had not been idle.

In 1916, shareholders of the cemetery association formed another for-profit company, the Evergreen Land Co. Using a $20,000 loan from the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Co. (which also held shares in the cemetery), Evergreen bought 19 acres of supposedly unused cemetery land to the north and west. In short, the cemetery’s shareholders sold the land to themselves — cheap.

The principals then enriched themselves by developing (such as putting in Warwick Trafficway) and selling off most of the 19 acres to buyers for more than $600,000 — a move that, in their April 1924 court filing, families claimed was an act of “collusion, fraud and conspiracy.” They argued that, by the cemetery’s own original charter, the land was only supposed to be used as a cemetery.

Families were demanding that the sale of lands to the unwitting buyers be set aside. Whatever empty land existed should be given back. Whatever money Evergreen and the Cemetery Association made should be turned over and used for the betterment of the historic graveyard.

In its defense, the shareholders of Evergreen and the Cemetery Association (being one and the same) argued that no remains were unearthed and they had done nothing illegal. The cemetery was a for-profit business, they said, that could do whatever it wanted with its land. Either way, it wasn’t up to the them to maintain the cemetery plots. It was up to the families.

The judge, in his May 1927 ruling, agreed, “No evidence of fraud.” He also said the cemetery association had no obligation to families to care for their loved one’s graves. But he did suggest that Evergreen would do well to make a voluntary donation to the cemetery to help assure its upkeep.

The court case was a turning point. In return for no more litigation, Evergreen gave $50,000, bringing the cemetery’s coffers up to $80,000. The idea would be to use investment interest for maintenance — a seemingly good idea, until the Great Depression struck.

In 1928, a new slate of preservation-minded officers, including Nellie McGee Nelson, and other descendants of early pioneers, took over. In 1936, the Cemetery Association voted to deed the cemetery to the city, which in 1937 turned it into a public park.

Today, no monuments or plaques mark potter’s field or the part of the cemetery where Black people are buried. Faries, the vice president of the historical society, said that the board has not yet discussed what might be the best way, if any, to properly honor the dead in those sections.

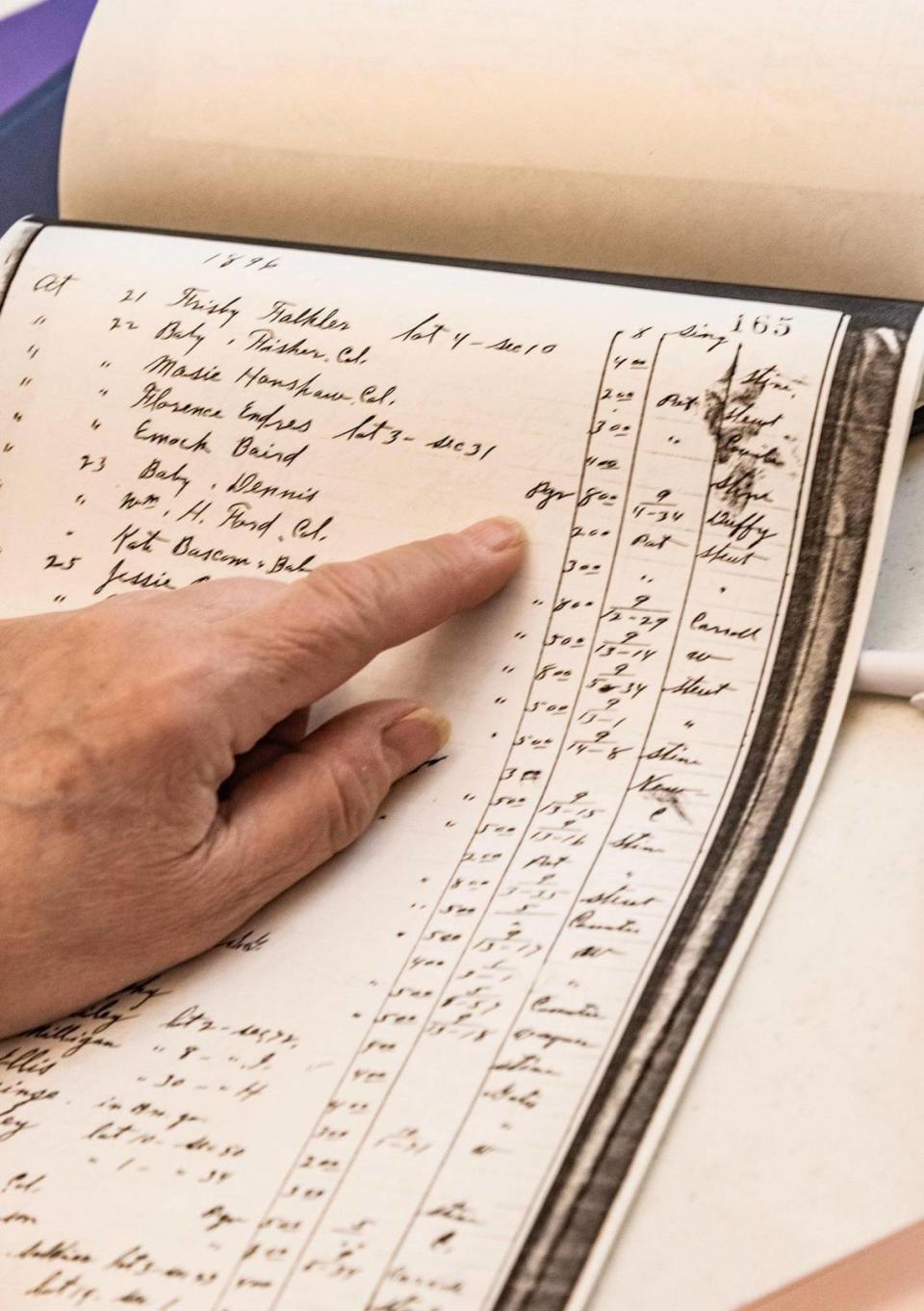

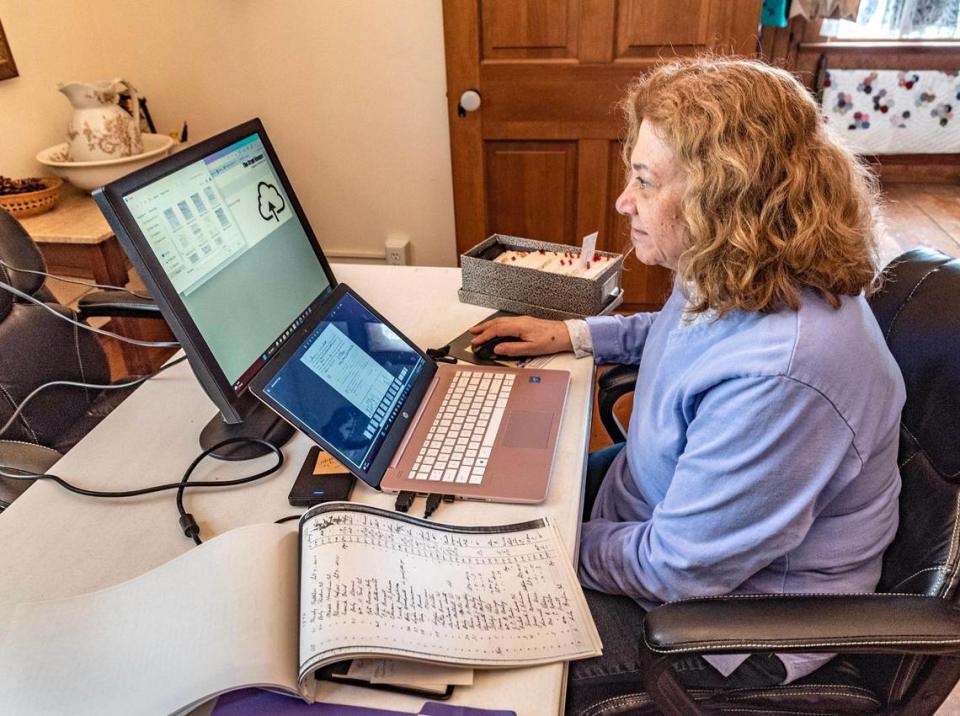

Beginning about five years ago, volunteers have been coming to the sexton’s cottage to honor the dead in a different way. They pore through the cemetery’s records, Jackson County death records, newspaper accounts, and whatever other material is available in order to digitize the names, biographical material, obituaries into their cemetery software, known as Crypt Keeper, to make it available to the public.

Although thousands of people’s graves go unmarked, with an unknown number desecrated, at least some of their stories can still be told.

“Even though they’re gone, they were still here,” Faries said. “They were still part of what made Kansas City what it is, and we need to remember those people. We want to be remembered whenever we’re gone. They were no different.”