Quebec's housing crisis is causing mental health issues, community groups say

Housing and mental health advocacy groups say Quebec's housing crisis is causing tenants' mental health to deteriorate and they are asking the premier to act.

Community groups say they're getting an alarming amount of tenants calling for help in despair.

Cédric Dussault, a spokesperson for the Regroupement des comités logement et associations de locataires du Québec, said some callers are expressing suicidal thoughts after losing homes they have lived in for decades and finding themselves with nowhere to go.

"It's not just materially and financially that this housing crisis is a burden for tenants, right now the toll on mental health is really heavy," said Dussault.

"We don't see a light at the end of the tunnel … We don't have solutions we can offer to tenants. Either there's no dwellings available, or they're completely unaffordable."

Tenants often have to fight for their rights, he said, which is an added burden for people who already struggle with their mental health.

Mental health resources not enough

Concerned individuals and community groups penned an open letter with over 300 signatures to François Legault saying the province needs to address the issue at its root.

Their demands include a moratorium on evictions, passing all home repossessions through Quebec's rental board and serious rent control measures.

Anne-Marie Boucher is a spokesperson for the Regroupement des ressources alternatives en santé mentale du Québec (RRASMQ), a coalition of organizations which co-wrote the letter. She said it's not enough to only focus on mental health resources.

"Yes, this help is important, but we need to act on the causes of the despair and distress. We have to fund more socialized housing," she said.

"Sometimes harsh living conditions are provoking mental health problems. Sometimes the fact of having mental health problems makes people more at risk of living in poverty … We have to act."

She said the groups affiliated with RRASMQ surveyed those who use their services, and over half of respondents say their mental health got worse as the cost of living rose. It's unclear how many people were surveyed or if they already struggled with their mental health, but Boucher said it included "hundreds of people all over Quebec."

She said it's clear that the current housing crisis is increasing anxiety for everyone.

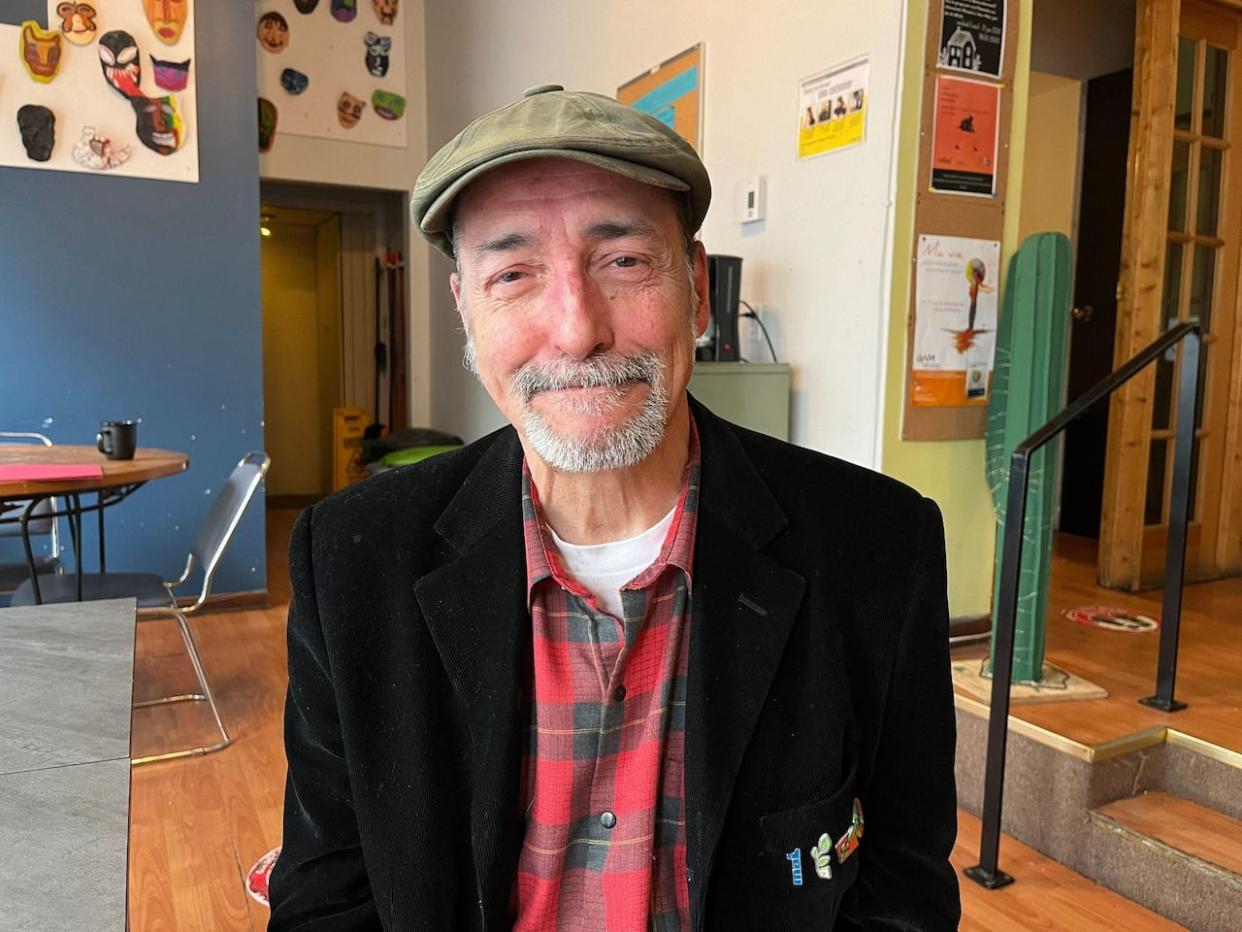

Peter Belland, president of the board of directors of RRASMQ who is also an artist, said about 80 per cent of his salary goes to paying his rent, leaving little for food or leisure.

"One of the main causes for me, for my depression, is poverty. I've always lived in poverty," said Belland who says he was diagnosed with depression 20 years ago.

Recently he has been having trouble with his landlord, who he said has been trying to evict him from his Montreal apartment without success.

"I can't leave. If I leave there, it's the end of my career and the end of my life."

Joe Flanders, a psychologist and psychology professor at McGill University, said it's not just people who have a history of mental health issues who are at risk. The risk of losing your home and quality of life can push anyone over the edge.

"People who are short on those resources, on that list of things that protect us, are more likely, or more vulnerable to having mental health problems," he said.

Quebec's housing minister, France-Élaine Duranceau, said in a statement it's important for the housing supply to increase.

She said the province earmarked $1.8 billion in the last economic update to build 8,000 new social and affordable housing units in the next six years — a far cry from the 50,000 affordable and social housing units housing groups say are necessary in the next five years.