Rare PoW camp newspapers show 'overlooked' WW I experience

A recent acquisition by the Canadian War Museum is providing a rare look into a First World War experience some soldiers had but rarely talked about later: life in a prisoner of war camp in Germany.

The weekly newspapers were produced by prisoners in the Rennbahn camp at Munster between 1916 and 1918.

By taking readers inside that world, the new collection could provide insight beyond the modern impressions of the conflict that revolve around the lives left behind on the European battlefields or the heroism of Canadian soldiers who stormed Vimy Ridge.

The papers also show how the PoWs at Rennbahn — some Canadian — coped with the strain of confinement and the uncertainty of when they would be free again.

"These newspapers offer you the door through which to walk and actually see what they're doing with their lives," says Nicholas Clarke, an assistant historian for the First World War at the war museum in Ottawa.

The copies of Echo du Camp de Rennbahn came to the museum via Dominque Enon, a Frenchman whose great-grandfather, Sgt. Henri Goupillon, was a prisoner there before he escaped. Goupillon was killed in action on Sept. 8, 1917.

Goupillon had started collecting copies of the paper, and his fellow prisoners kept that up in his honour after his escape, later presenting them to his daughter, Enon's grandmother.

"That fabulous collection have slept ... in a pillow of straw in the ceiling of our family house," said Enon, who had first offered the papers to French museums but they weren't interested.

Clarke says the papers, which have undergone conservation techniques, are "amazing" and "very, very rare."

"We're exceptionally fortunate to have them."

Fortunate in particular, he suggests, because of the opportunity the papers have to broaden modern-day understanding of what the First World War was really like.

"When we think of the First World War, for a variety of reasons we tend to think of the mud and horror of the trenches, or Vimy Ridge, these great Canadian moments …. and we don't consider the fact there are so many prisoners of war," says Clarke.

"It's often overlooked."

Not like The Great Escape

By October 1918, there were about 2.5 million prisoners of war in Germany. Clarke says about 3,800 of them were Canadian. About 1,400 of those prisoners were captured during the first major battle the Canadian Expeditionary Force saw: the second battle at Ypres in April 1915.

For those prisoners, day-to-day life was not necessarily what we might think.

"Our tendency when we think of prisoner of war camps is … coloured through the lens of the Second World War," says Clarke, and what we saw on the small or big screen watching Hogan's Heroes or The Great Escape.

"It's a little more complex than that in the First World War, not to say though that it wasn't hard, because it certainly was."

PoWs died from pneumonia or overwork and food became scarcer as life in Germany continued under a blockade.

Yet within Rennbahn camp, soldiers developed a community of their own. There was a theatre, a library, a school where they could learn trades. They wrote poetry and drew cartoons. And the camp newspaper had reports about it all, written in French and English.

"There are few amongst us who have not had reason during our stay in the camp to appreciate to the full the Rennbahn Central Library, deservedly one of our most popular institutions," begins one article in the Nov. 25, 1916, edition.

"How many hours of tedium and of weariness have been enlivened by the consolation which is to be found upon its well-lined shelves, and how much vicarious pleasure has it provided!"

'Happy' prisoners

Clarke acknowledges that it might come as something of a surprise that the Germans would have allowed that development of a community – with its own newspaper – to go on within the camp.

But there was a reason, he suggests.

"It's easier to deal with happy prisoners than it is with unhappy prisoners."

Happy, of course, being a relative term. But at least the soldiers had an outlet, and something to do with some of their time.

Still, within the newspapers there is acknowledgement that the uncertainty of their situation was weighing on the prisoners.

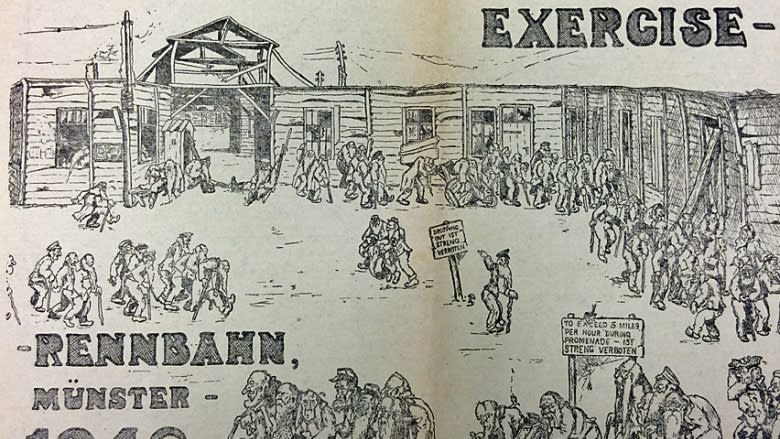

A cartoon showing them as old men doing exercises in 1946 alludes to their worry about when they might be free. Concern about how they might adjust to civilian life also emerges.

"The cartoons are very satirical, but as with most satire, there is a very serious concern or point to be made," says Clarke.

Whatever the experiences reflected in the newspapers, they might not have been recounted once the soldiers got home.

A question of masculinity

"A lot of prisoners of war — and it's always dangerous to speak in generalities — didn't speak about their experiences for a variety of reasons, one of them being they're worried about being deemed as cowards because they surrendered, and there's the question of masculinity involved in that," says Clarke.

While memoirs were written by some prisoners of war, many of them were written for propaganda purposes, he says.

But combine the insight offered by the camp newspapers and a photo album the museum acquired several years ago that shows a Winnipeg soldier's PoW camp experience, along with other camp material, and you have a sense of the day-to-day experiences prisoners faced. The material also reflects the multi-ethnic nature of the camp, Clarke says.

It's hard to determine authorship of much of the writing within the papers. Some articles are unattributed. Others appear with obvious pseudonyms.

But it's clear within the pages there is at least some Canadian input.

One article in the Feb. 3, 1917, edition written by someone calling himself "Optimus" appears under the headline "The Canadian," and runs for one and a half columns, "not an insignificant amount of the English section of the newspaper," Clarke says.

Making the best of the situation

It discusses the character of a Canadian, finding a hardiness and stoicism, along with a penchant for talking about the weather.

"He has learned the happy knack of shifting for himself — of making the best of conditions which others would find intolerable — and he contrives to turn the most unlikely objects to useful ends," the author writes.

At the bottom of the page, however, there is a hint of another reality of war.

Under the headline "Missing Comrades," there's a request for information "as to the fate" of Privates A. Haywood and John Edward of the Canadian Infantry.

Enon, who lives outside Paris, doesn't know if his great-grandfather spent any time with Canadians in the camp, but he remembers being told that he was very interested in people from other countries.

"I'm sure that he tried to spend time with them ... speaking about their countries, how they lived, what did they eat."

Enon's interest in seeing the papers find a home with the Canadian War Museum was sparked in part by his time working with members of the Canadian Armed Forces after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

He says he is happy the papers will be archived in the Ottawa museum.

"Now, all the students, all the researchers and historians, can share what the prisoners were doing in that prisoners' camp."

Researchers and others interested in viewing the copies of Echo du camp de Rennbahn can do so by making an appointment at the Canadian War Museum.