Regina's decades-old north vs. south of Dewdney Avenue rivalry explained

Ryan Malley says living south of Dewdney Avenue in Regina — SOD for short — runs in his family.

So much so, his parents bought a trio of homes on the same Whitmore Park street because of their love of the neighbourhood. In their 26 years on Castle Road, they lived in three different houses.

The first was Malley's childhood home. Then they downsized to the bungalow across the street. Years later, when his grandparents grew older, his parents bought the house next door to make sure they were nearby.

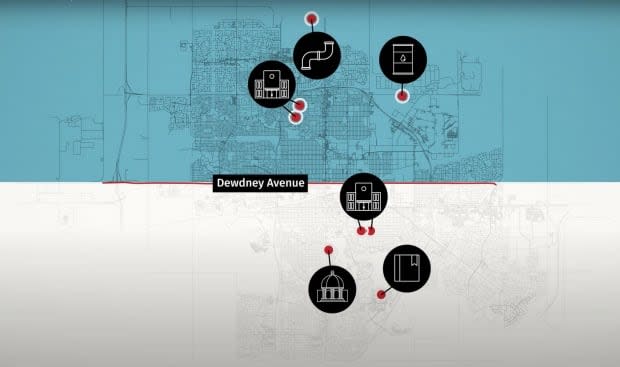

"South of Dewdney, we have everything: we have the stadium, we have the legislature, we have the downtown, Wascana Park," Malley listed.

That's why once he and his partner, Jacqui Cameron, moved in together, they bought a home in Harbour Landing — again, in the city's south. And for years, they lived there with her son, Rylan, until he was placed in a developmental class at Winston Knoll Collegiate located in Regina's northwest.

Not having grown up in Regina, Cameron said she didn't realize there was an emotional attachment to the south and north ends of the city until they were forced to move.

"I don't think I really grasped how much it mattered to [Malley]. I'm like, 'We're just moving to another neighbourhood.' And then to find out he talks about it sometimes," she trailed off with a laugh.

"Even though it was the same city, it was like learning a new town," Malley interjected, working to make his case. "You get used to certain things in the south end and you kind of have to relearn everything."

Although they've lived north of Dewdney — or NOD — for three years now, Malley said he'll always consider himself SOD.

"SOD is home; it's where I grew up. It's the part of the city I know the best."

The history of NOD and SOD

According to Jerry Flegel, a longtime Regina real estate agent and former city councillor, the NOD and SOD rivalry began in the 1970s.

"The biggest [stereotypes] in the north were that they're rough and tough, and the south-end people got the tag 'south-end cake eaters,'" he said, emphasizing the name calling was initially between those who lived in Albert Park and Coronation Park.

LISTEN | Bionic Bannock Boys wrote a song about why living north of Dewdney doesn't deserve a bad rap:

Flegel said the NOD versus SOD rivalry sprung up most often between high schools — specifically, with Miller High School and Balfour Collegiate in the south, and Thom Collegiate and O'Neill High School in the north because those schools shared streets.

"Kids started to party, and the [O'Neill] Titans football team would go crash the Balfour party and then the fights were turned on," remembered Flegel, who attended Miller in the '70s. "Because there's a gap in between [both schools], Dewdney was just the natural divider."

The gist of the teasing was based on class stereotypes.

With the Co-op refinery and Evraz — or Ipsco, as it was known — in the north, people who lived in that end of town were labelled "blue collar workers."

Then, with the legislative building and the university in the south, that's where the politicians, academics — or "white collar workers" — lived.

Aydon Charlton, who went to high school in the 1960s, maintains the divide was the train tracks near Mosaic Stadium.

Back then, he said the terms NOD and SOD were never used, but the stereotypes ran deep and were taken a lot more seriously.

Charlton remembered the nights when he would have to cross the tracks to visit his girlfriend who lived on Regina Avenue. While walking home, he said he'd routinely be stopped by police.

"It became a standing joke: as soon as you crossed the CPR tracks, near where the Lawson Pool is located, you'd get stopped. And I'd never get stopped on the south side of the CPR tracks — only on the north side," Charlton recalled. "It made me quickly aware of the difference in attitudes that the police showed to the kids from the north side of the tracks versus kids from the south side."

WATCH |Cat Abenstein recites a poem about being from north of Dewdney at a Regina poetry slam in 2015:

'The best of both worlds'

Growing up in the late 1960s in the Rosemont area, Layton Burton confirmed the stereotype always went that those in the south were mostly white-collar workers, while those in the north typically held blue-collar jobs.

"I remember my parents used to take us at Christmastime and drive us around south-end neighbourhoods to show us the Christmas lights because the south end tended to have more Christmas lights than the north," Burton said.

Fast forward to high school, and he noted the terms NOD and SOD became everyday vocabulary — and the clichés evolved.

"There was this fallacy that all north enders had muscle cars, and if you drove your muscle car past the McDonald's on Dewdney Avenue, some Mercedes Benz would come up and honk at you and give you the finger," he said. "We really felt that way."

About 30 years ago when he met his wife, Susan Zmetana, Burton was drawn to the opposite end of the city. But he didn't mind, joking the experience of moving SOD was "eye opening" after growing up as an "NOD kid."

For Zmetana, staying south had nothing to do with what she considers outdated and hurtful stereotypes.

"I think it's the old-style neighbourhood and the mature trees," she said, noting she grew up across from Wascana Park. "Plus, you have family and friends who all grew up in the same neighbourhood. It's pretty compelling to stay in the vicinity."

Unlike Malley who's staying true to his childhood roots, Burton said he's content where he's at.

"I still consider this body to be NOD and some of my sensibilities, but I have to admit … I'm a south ender now and I'm happy to be," he said. "She's what brought me here, and I guess I've been able to live the best of both worlds."

How community rivalries are born

When it comes down to this rivalry, Bob Patrick, the chair of the regional and urban planning program at the University of Saskatchewan, said it's common for people to become defensive about where they're from and to show pride in that.

"Over time, areas evolve and have recognition. [Residents] get a sense of who they are, what they reflect and their values," he said.

That stems from topophilia, he said, otherwise known as "a strong sense of place."

"After a period of time, when we live in a city — or even a smaller town — we begin to identify with that neighbourhood or that region that we're living," he said. "That identifier becomes a reflection of who we are, so it becomes easy to become attached."

Patrick said that sense of place can be found in a historical connection where there are family ties or simply in a neighbourhood with accessible amenities.

Overall, he said when there's competition between city neighbourhoods, it tends to create a healthier community as a whole.

"At least they're talking about their neighbourhood and at least they're thinking about their neighbourhood," Patrick said.

The future of NOD and SOD

Current high school students tell CBC News the rivalry between north and south enders is lukewarm — if it even exists at all.

WATCH | The CBC's Jessie Anton asks some Regina teens whether they're familiar with "NOD" versus "SOD":

"I don't think anyone really cares anymore," said 14-year-old Jayce Langton. He said he's briefly heard of the terms NOD and SOD but doesn't know anything beyond what the letters stand for.

Angelica Babchuk said she's never heard of those terms, adding she doesn't think city-wide rivalries exist for teenagers anymore.

"It kind of sounds old school. I'm not going to lie," the 15-year-old said. "Maybe on social media [there are rivalries], but there's nothing really specific."

Zmetana wasn't surprised when she heard young people don't talk about the historic rivalry she had growing up.

"These are not even relevant terms or thoughts for anyone under 40 or 45," she said. "It's just the glut of people in our age group who are trying to hold on to the past."

Her husband, on the other hand, is disappointed the banter is fading.

"I'm kind of sad that perhaps young people in high school and late elementary school these days don't have that same kind of neighbourhood pride that we had in the '60s and '70s," Burton said. "I don't think it was a bad thing for us — I think it made life a little more interesting."