Religion, school discourages Macon abortions, where teen pregnancy is higher than US average

As a senior in high school, Shy’kemia Lundy didn’t know she was pregnant until two months after having unprotected sex, which would’ve left her with no option to have an abortion in Macon.

By 17 years old, Lundy had sex without a condom a few times and figured the next wouldn’t be any different. Then she noticed symptoms.

“I feel like it happens with a lot of girls that never really had the freedom to just be a teenager, so when you finally get out there, you just go with whatever, just that first impression of a guy,” Lundy said. “People need to communicate more about this stuff. That’s how I got here.”

The now 19-year-old stood on her family’s front porch with her 1-year-old son clung in her arm, sharing that she thinks there’s a conversation gap on safe sex and abortion for teenagers at home and at school. Lundy grew up in Macon but attended high school in Ohio to live with her father. She got pregnant while in Ohio, then later moved back to Macon.

“We used to have little consequences like, ‘You better be in the house before the streetlights come on,’” Lundy said, recalling her parents’ advice. “I didn’t really know too much about how my body worked, like how the female body worked.”

This lack of discourse is one of several factors which contribute to Macon-Bibb County’s decades-long trend of teenage pregnancies.

Macon’s teenage pregnancy rate is significantly higher than the state and national averages, an issue that local residents and activism groups are trying to fight. But abortion often isn’t part of the conversation in that fight. Religion and policy are factors for that.

The county reported 40.1 pregnancies per 1,000 residents among 15 to 19 year olds in 2022, the most recent data by the Georgia Department of Public Health.

The county saw more than double the state’s average of 16.6 pregnancies per 1,000 in that age range. It also surpassed the U.S. teen pregnancy rate of 13.5 births per 1,000 teens between 15 and 19 years old.

There are zero abortion providers in Macon, the fourth-most populated city in Georgia. The nearest abortion clinics are in Atlanta and Columbus, each more than an hour drive away.

The Telegraph interviewed local advocacy groups, medical providers, public health officials, church congregants and teen mothers who explained factors that have contributed to the cycle of teen pregnancies. They cited limited local health care, restrictive abortion legislation in Georgia, abstinence-based discourse in Middle Georgia’s deeply religious Bible Belt and inadequate public school sex education curriculum.

Teen abortions ‘nearly impossible’ under GA law

While abortion is legal in Georgia until up to around six weeks of gestation or when a fetal heartbeat is detected, the state’s legislative restrictions make it “nearly impossible” for teens to actually undergo an abortion, according to Jaylen Black, vice president of communications for Planned Parenthood Southeast.

Abortion is not the only answer to combating teen births, but Black said it is an essential option when other medical challenges make child birth and child care difficult.

“You can’t have abortion bans and not have paid leave. You can’t have abortion bans and have hospitals closing in your state. You can’t have abortion bans and be one of the top five states with the worst health care infrastructure,” Black said, referring to a Harris Poll survey that ranked Georgia as the worst state for health care in 2023.

Since 2013, 12 rural hospitals across the state have shut down, many due to financial trouble. This year, 18 out of 30 rural hospitals in Georgia are at risk of closure, according to a report by Chartis, a health care advisory firm that serves 40% of U.S. hospitals. While Bibb is not classified as a rural county, the majority of its surrounding counties are, according to Georgia’s state office of Rural Health.

Within the six-week timeline for an abortion required by Georgia law, doctors are required to notify a minor’s parents or guardians before their child has an abortion. There are “unusual circumstances” that allow a minor to bypass parental involvement, including if the minor is married, or when “the minor believes it is not in the best interest” to inform them, according to a document by the Georgia Department of Public Health titled “Abortion: A woman’s right to know.”

But this effort requires a judge to agree. If a minor or doctor opts to not notify parents or guardians, they must file for a judicial bypass in juvenile court. This is approved if the judge deems the minor is mature enough to choose to have the abortion without parental involvement.

Georgia law also requires anyone having an abortion to undergo a counseling appointment in person or by phone with their abortion provider, then wait at least 24 hours before having the abortion.

Rosalind Simson, philosophy and gender studies professor at Mercer University, has researched moral and legal intersections of abortion. She explained the lengthy process for a teen to access the medical procedure or pill in Georgia.

“You can’t call them up and say, ‘Can I have an abortion today,’” Simson said. “The likelihood that you can get yourself to psychologically make up your mind that you’re going to have an abortion, and that you’re going to be able to get an appointment for counseling, and then wait 24 hours to have the abortion … there’s almost no time element there, especially for teenage girls for whom they don’t know where to start.”

Lundy knew “something felt different” the last time she had sex before she got pregnant, but she didn’t take a pregnancy test until about two months afterward. Even then, she waited some time before she told her parents and saw a doctor.

“I kind of just didn’t tell nobody at first, but then after a while, I started looking at how I truly feel,” she said. “It’s kind of hard to accept it.”

The Georgia Department of Public Health’s online abortion handbook, outlined by House Bill 197, includes five pages of abortion risks, but merely one page on risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth. The site explains medical and long-term risks, emergencies and “the emotional side of abortion,” but only lists medical risks of pregnancies.

The unbalanced ratio of information on the government website makes abortion seem “much more dangerous” than pregnancy, Simson said.

“So it’s not that anything here is inaccurate, as far as I know, it’s just the emphasis is certainly skewed.”

Pregnancies and child births are far more dangerous than abortions, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data from 2013 to 2018 shows the national case-fatality rate was 0.41 abortion-related deaths per 100,000 legal abortions. The rate of maternal deaths was 17.35 per 100,000 live births.

“Many teens believe that abortion is sinful and even if they’re not that religious, a lot of people feel that abortion is immoral,” Simson said. “It’s certainly the message, especially in Georgia, that the legislature is giving us.”

How is sex, abortion discussed in GA churches?

About 60 years ago, another Macon resident, Lauraetta Jackson, got pregnant at 15 years old. She grew up in a low income, religious Black family, where the conversation of abstinence overshadowed actual steps needed to avoid, or respond, to pregnancy.

“People just tell you, you better not get no baby and whatever … and then children like me say, ‘Well how did I get here?’” said Jackson, who did give birth as a teen. “You hear, ‘you better behave yourself, you better not be out there messing around,’ but then end up getting a baby.”

“I’m sick of talking about abortion. Talk about birth control,” Jackson said. “You don’t have to have an abortion if you go ahead and prepare before you have sex.”

However, similar setbacks caused another situation to occur a few years ago when a 16-year-old family member was also pregnant and didn’t opt for an abortion.

“It’s a sad situation really,” Jackson said. “(Teen pregnancy) has gotten to be really more of an epidemic from what I can see in the Black lower income communities.”

Teen pregnancies do predominantly impact low income, Black communities in Macon. In 2022, 86% of the county’s 212 births involving mothers between 10 and 19 years old were Black, according to previous reporting by The Telegraph.

About a quarter of Macon residents were in poverty, according to the 2022 U.S. Census Bureau. The county exceeded Georgia’s poverty rate by about 12% that year.

Jackson recalled one instance where a woman missionary at her church tried to hold information sessions on safe sex practices. Other than that, she said contraceptives, birth control and abortion are never discussed during church services.

“I don’t think it is (discussed) at all. I know it wasn’t where he was,” Jackson said, referring to her husband’s church. “So ‘teen pregnancy was the young lady’s (fault),’ but it don’t happen on its own, and seems like society never says that.”

Some of the South’s most common religions under the United Methodist, Southern Baptist and Catholic churches were split about their stances on abortion in recent years.

The United Methodist Church rejected late-term abortions in 2022, but affirmed abortion as a solution “when ‘tragic conflicts of life versus life’ happen during pregnancy,” according to a 2022 report by the church, referencing its Book of Discipline.

A third of Southern Baptists said abortion should be illegal in all cases, according to a 2021 Gallup report.

The Catholic Church itself opposes abortion, and 22% of U.S. adult Catholics said abortion should be legal in all cases, according to the most recent data by Pew Research Center.

No abortion clinics in Macon

Macon almost had an abortion clinic in 2018, but a Catholic pro-life pregnancy clinic and protesters stopped it from breaking ground.

The Macon-Bibb Planning and Zoning Commission approved Summit Medical Center, an abortion clinic based in Atlanta and Detroit, to lease a property at 833 Walnut St. in 2018. But after hundreds protested and five local businesses sued the abortion center and Planning and Zoning, The Saint Maximilian Kolbe Center for Life bought the property instead.

The nonprofit offers pregnancy testing, ultrasounds, adoption plans, prenatal care referrals and counseling for women who regret having an abortion. It sees about 500 clients per month, the organization reported.

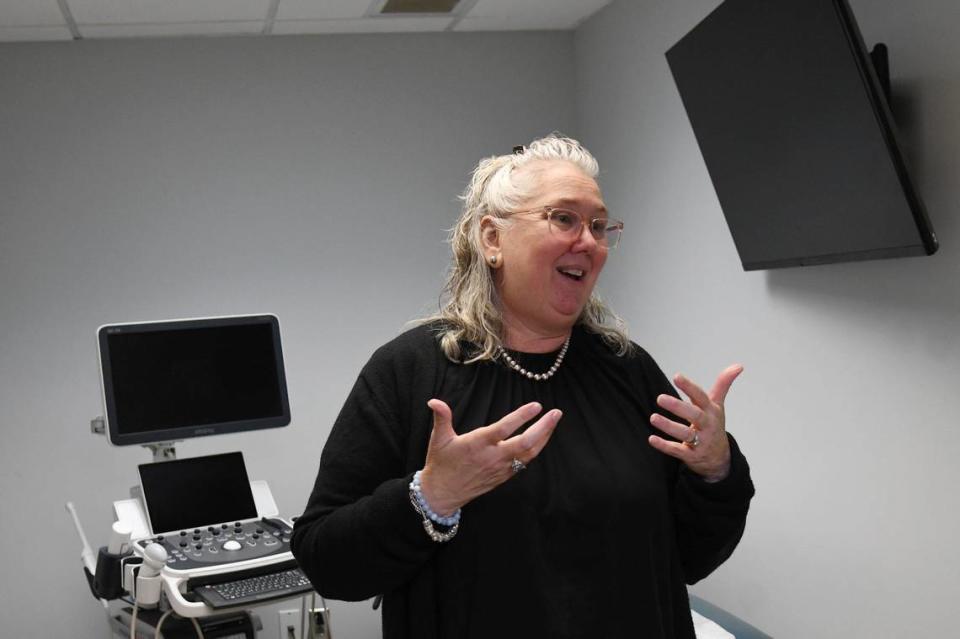

Ann Beall, executive director of The Kolbe Center, said the clinic does not assist or refer anyone who seeks an abortion.

Beall recalled an incident when a 13-year-old girl visited The Kolbe Center initially seeking an abortion, but then decided to go through with the pregnancy.

“My encouragement is always going to be, even if you don’t want to parent … adoption is a beautiful thing,” Beall said. “As a family, you can support her through having killed her child, or you could support her through having made an adoption plan and loving that baby more than she loves herself.”

Beall recalled when a relative told her she “over-exaggerates” abortion risks.

She said that relative would say, “’I’m sure you make worst case scenario, you make it sound horrible,’ and I’m like … I am telling these young women the facts that I know, and the facts that I know are emotionally and physically this is bad for you.”

This sort of information “is a lot of stuff that would certainly scare somebody,” Simson said.

The World Health Organization has proved abortions are safe as long as they are performed under its standards.

‘That message of ‘no’’

Abstinence-only advice is seen throughout central Georgia’s public school sex education curriculum.

Keri Hill, vice president of programs and training for the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power and Potential, leads trainings which Macon public school teachers undergo before they teach sex ed.

The first time Macon students receive a sex ed lesson is in ninth-grade health class.

However, the organization advocates to start these conversations in kindergarten, far before students reach puberty. While the state guidelines are “absolutely designed to be that way, it is not often that way,” Hill said.

“With comprehensive sex ed curriculums, it’s usually something that should take place throughout K through 12,” Hill said. “Just starting with the anatomically correct terms, and starting with what does a healthy friendship look like, and the fact that we should celebrate our differences.”

The Georgia Department of Education requires “age appropriate sexual abuse and assault awareness and prevention education in kindergarten through grade nine,” according to the state’s health and physical education program plan.

But in 94.3% of Georgia high schools from 2017 to 2018, lessons on pregnancy, HIV and other STIs could start as early as ninth grade through as late as 12th grade, according to the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the U.S., a sex ed advocacy nonprofit organization.

The data covered the school year prior to the CDC’s release of the 2019 School Health Profiles, which measured school health policies and practices nationwide.

About a quarter of the state’s high schools did not teach students about contraceptive methods other than condoms, the Sexuality Information and Education Council reported.

While a unique curriculum is laid out for each school district in accordance with Georgia standards, individual schools can select to add or remove certain topics from the curriculum, Hill said. The Bibb County School District told The Telegraph they could not confirm whether their schools use the full Family, Life and Sexual Health curriculum.

An aspect of the training for teachers guides them how to remain unbiased, but there is no guarantee the topics taught to students are discussed in the same way GCAPP trains teachers.

“There are a number of different topics that are … always a part of the trainings. We can’t guarantee that’s always part of the discussion that actually happens in the classroom,” Hill said.

Overall, she said Macon is “on the right track,” in comparison to other counties because it uses a research-based approach and discusses contraceptives.

The battle against teen pregnancy is a traditional cycle that starts with parents, Hill said.

“Many of us didn’t have the conversations at home ourselves with our parents … it’s just that message of ‘no’ at home, and it wasn’t the ongoing dialogue,” Hill said. “So it’s difficult when you become a parent when you didn’t have that discussion to reflect on.”

Jackson agreed. Her teenage relative didn’t disclose to her mom that she was pregnant until after the baby was born.

“I come home, and she was up there in the sun room talking to her father … I said, ‘she’s pregnant right?’ and he said, ‘No, she had the baby.’”