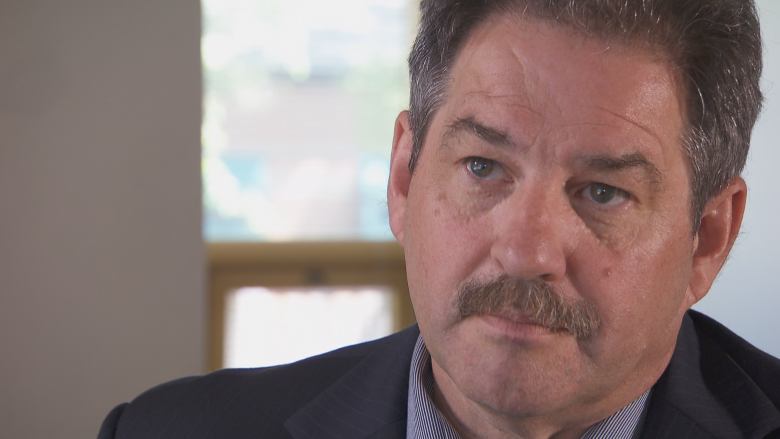

Retiring Staff Inspector Mike Earl speaks candidly about nearly 40 years with the force

Mike Earl has no regrets. "None whatsoever," he insists.

After a long and at times controversial career with the Toronto Police Service, the staff inspector is stepping down on what he says is a high note, from a job he says he "really, truly had a passion for."

In his nearly 40 years, Earl developed something of a reputation when it came to police news conferences. He's the man the responsible for terms like the "lunchtime bandit" and the "pathetic parasites," colourful names to some, but downright discriminatory to others.

"My passion is actually on the chase for the bad guys," he told CBC Toronto's Dwight Drummond in an exit interview. "That's why I like dealing with the press conferences. That's my way of helping my investigators still help solve a crime at the end of the day."

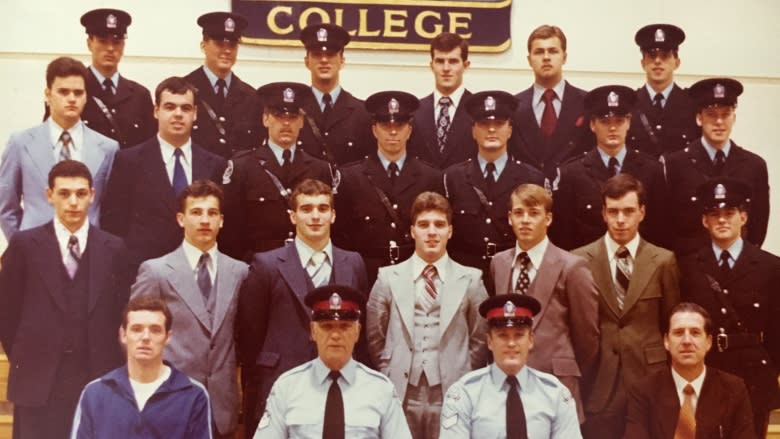

From the turkey farm to the force

Earl became interested in policing in high school. He got his chance in 1978 when he joined as a cadet, a big change from working on a turkey farm in the Waterloo region.

His early years with the force saw him working out of 11 Division as a uniformed constable. From there it was undercover work for three years, largely on with the prostitution task force at a time when an influx of runaways and missing girls being recruited by pimps were plaguing Queen Street West.

It wasn't long before he was promoted to sergeant at 13 Division, taking over the major crime unit. Late nights were par for the course.

He was recruited to the hold-up squad from 1990-1999 at a time when crack cocaine was at its height he said. For five years after that, he investigated other cops working at internal affairs, a job he says was "an eye opener," but work that "needed to be done."

The year he was promoted to inspector was the year of the gun, he said. Going to work often meant attending a shooting scene. And not long after, then-chief Bill Blair asked him to join the guns and gangs force.

'For the most part it worked'

Over the course of his rise up the ranks, Earl was often in the spotlight, the face of the force at media conferences and in front of reporters.

One of the most heated of those moments came late last year, when he referred to a group of 16 young men allegedly responsible for some 50 robberies in the Greater Toronto Area as "parasites."

That drew the ire of many in the black community, including activist and commentator Desmond Cole, who charged that Earl was "telling the world we're not human."

"There's been commentary about it and I think there's been a time when people weren't happy with some of my comments," Earl acknowledged about moments like that one.

"But I think I had the support of the chief," he said. "My goal was to solve crime, it was to get media attention so we could get tips and generate conversation ... And for the most part it worked."

Thirty-nine years came and went quickly, says Earl. Not so for his wife, who's been waiting for him to make her a cup of coffee in the morning for the better part of their marriage, he quipped.

Today, they have two sons, the youngest of which has expressed a budding interest in policing, something Earl is encouraging. "It's done me no wrong. I've enjoyed it and it's given back to the community."

Complexes built 'like fortresses'

But as he steps away from his role, Earl has some concerns for the future of the force and the neighbourhoods he spent so many years working in. Gang violence weighs on his mind, as do its "root causes," which he says have gone unaddressed for the past 30 years.

The blame for that, he says with frustration, often falls on police

"I think some of these communities need to be dismantled like they did in Regent Park so the recruiting stops… We have to stop the cycle of gang recruiting and gang warfare that continues and I think one of the things they really need to look at is maybe dismantling.

"These complexes were built like fortresses years ago. You have one neighbourhood pledging allegiance to that neighbourhood and fuelling wars against other neighbourhoods." That, he says, is "causing all kinds of gunfire and black on black murders."

So what are the root causes?

Earl says he doesn't have the answers, but looks to the politicians and faith and community leaders to zero in on them.

One thing that isn't helping, he says, is the Jordan decision — a recent ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada that reduced the amount of time defendants could be made to wait before their cases go to trial. Earl believes that decision has resulted in many of those cases being thrown out of court.

He's also frustrated by what he perceives to be the loosening of sentencing rules around handgun offences.

"How are we helping the situation by softening the rules?" he asks.

'We're the ones with the body bags'

The new regulations brought in by the Toronto Police Services Board to limit the practice of carding are also adding unnecessary confusion for officers, he says. Those rules came in after activists in the black community complained that officers were singling out predominantly young black males, arbitrarily stopping them them and recording their personal information.

To be clear, Earl refers to the practice as "investigative contact," maintaining "carding" is an offensive term coined by the media.

The rationale for the practice was never properly explained to the public, he says. But contact is something he insists officers have to be able to do. "That's how we get information," he says.

As he leaves a life of policing, he reflects on what he says is the public's inaccurate perception of the communities he's worked in and the people who live in them.

"You have low-income families that are trying to support their children in these neighbourhoods, and a lot of time working long hours, so these children are left in these neighbourhoods ... and they're easy targets for these elder gang members to recruit," he said.

"I think that there's a lot of misconceptions about these communities. There's a lot of good people."

But it's not only the communities that are misunderstood, he says.

"It gets tiresome at times when the blame comes to the police and the judiciary when we have to deal with the end results all the time. We're the ones with the body bags and the police tape."