How a Ridgetown teacher is part of the fight to preserve the Lunaapeew language

An Indigenous teacher in Ridgetown, Ont. is part of a mission to keep the Lunaapeew language alive.

For the people of Delaware Nation in southwestern Ontario, Lunaapeew is more than just their language — it is integral to who they are as people, but a painful history of racism and residential schools has left behind only a handful of people who speak it proficiently.

And that's making the push to pass it on to the next generation all the more urgent.

"Our language is a huge part of what makes us Delaware," explained grade school teacher Kristin Jacobs.

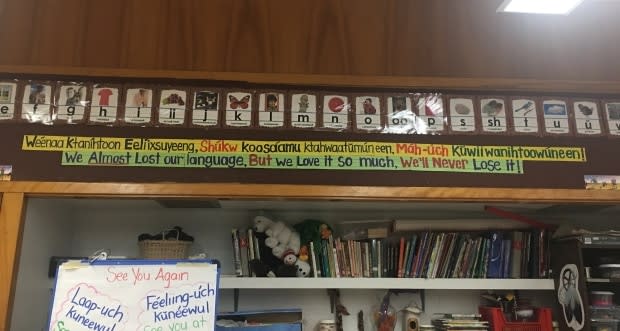

She is part of a small group of people studying the language from one of the last known proficient Lunaapeew speakers in the region, elder Dianne Snake in Delaware Nation at Moraviantown.

"Dianne is getting older, and we want to make sure we get as much of the language as possible from her," Jacobs said, adding that time is critical.

'Save our culture'

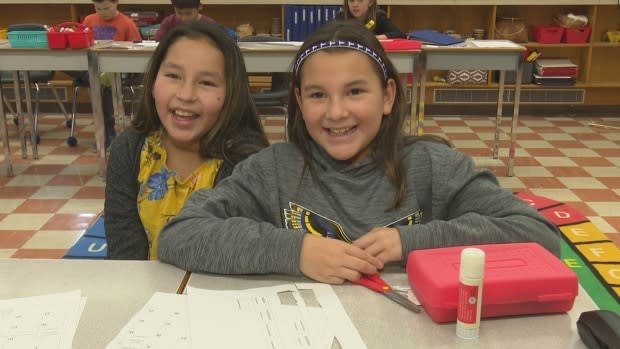

Now, Jacobs is passing on the language to students from Grade 1 to Grade 8 at Naahii Ridge Public School and Ridgetown District High School. Her colleague Angela Noah also teaches Lunaapeew at the high school for students from Grade 9 to Grade 12.

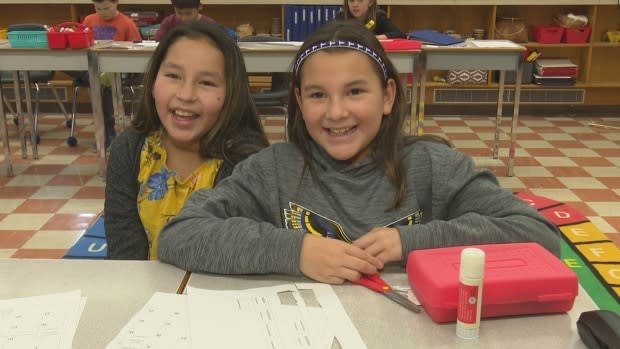

For the Indigenous students in the classes, the preciousness of the lesson is not lost on them.

"I don't want to lose our language," said Grade 4 student Kara Cornelius.

"We hardly don't have any more speakers left and my grandmother's mother spoke it and my cousin is now speaking it. So, I want to learn the language too."

Grade 5 student Devon Reaume said the goal is to "save our culture."

The loss of the language

Delaware Nation Councillor Gordon Peters said the knowledge of the language dissolved over the years because of the discrimination Indigenous people have faced, and explained that there are only a "handful" of first language speakers left.

"That's what happens to us in our families. A lot of our older people never thought that the language was ever going to be important to us because being an Indian in those days was not a good thing," he said.

"The racism was extremely heavy."

Peters said as a result, the older generation didn't pass on the language in order to protect the following generation from the pain they themselves had gone through.

Though his mother spoke Lunaapeew, he never learned the language himself. As she was getting older, Peters asked her to teach him, but she passed away during that time.

He said he wishes he had asked her sooner.

Jacobs explained that she also was never taught at home, because the two generations before her were sent to residential schools, which is where a lot of the language was lost.

That's why now, Peters explained, there's a real emphasis on the importance of the language, "and making sure that it's an important part of our lives that we have to retain so that we know who we are as the original people of this land."

'Another generation of speakers'

The fight to save the language started years ago, and Peters said his own mother was originally a part of that.

He said it was a challenge trying to run language programs at Delaware Nation, so eventually they developed an immersion program to give adults the tools to ultimately teach children.

"It equips us for another generation of speakers.... Immersion seems to be the only way that we can move forward," he said.

There were five participants in the community who stuck with the program — including Jacobs — learning from Snake.

"I'm really, really thankful to my language teacher Dianne," said Jacobs.

"Being able to work with her and for her to pass her knowledge on to me is the greatest gift of all."

Jacobs explained that Snake's first language was Lunaapeew, and that she didn't start speaking English until she was seven or eight years old.

"Most of those elders who grew up with the language in their home as their first language have passed on, so we're left with Dianne who is one of the last — I would say last, because I'm not aware of any others."

Jacobs and the group of five studied with Snake three days a week for nearly four years, but found that they needed even more time, so the five of them took a year off from their regular jobs to study with Snake for a year. They also recently graduated from a language certification course at Lakehead University, which they attended every July for four summers in a row.

Peters noted that Snake has been a dedicated language teacher in the community for decades.

"She's a spectacular woman," said Peters.

"She knows her language. She helps wherever she needs to help."

Hope for the future

Jacobs said she's grateful to be a part of the movement to save the language as well.

"It's very fulfilling knowing that I'm helping our community by passing on the language to the students and maybe someday one of them will be a language teacher too," Jacobs said.

But she's not the only one passing on this knowledge. Her other colleagues who have been learning from Snake are teaching youth and community members in the area as well, like Noah at Ridgetown District High School.

Peters said Jacobs has had an impact on many young people, and it's moving for him to witness the effect it's having.

"Oh it's just it's very emotional. I can tell you that."

He hopes to see that impact continue into the future as that next generation of Lunaapeew speakers is created.