Rudy Deutsch, WWII medic, recalls time with 'poor, bloody' infantry

Rudy Deutsch has been defying the odds for nearly 70 years.

The 91-year-old veteran fought through 40 battle lines in North Africa and Italy during the Second World War and returned home in one piece.

Just over a year ago, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and told he had only months to live. Yet, he still lives at home, surrounded by photos and memorabilia – the evidence of a full life.

“They gave me a month to live, [but] I’m still here," he says with pride.

Deutsch, who’s watched as all of his old war buddies passed away, says remembering their sacrifice remains important – particularly in light of Canada’s continuing military involvement in combat missions overseas.

“To see the few veterans who are left alive and I’m glad … they’re having interviews with veterans and remembrance programs so the younger generation knows what we went through.”

Shipping out

Growing up on a farm north of Regina, SK, Deutsch was already a practised sharpshooter when the war began.

Because he had family living in Bavaria – and possibly even fighting for the other side – Deutsch opted to put aside that training when he was drafted in 1943.

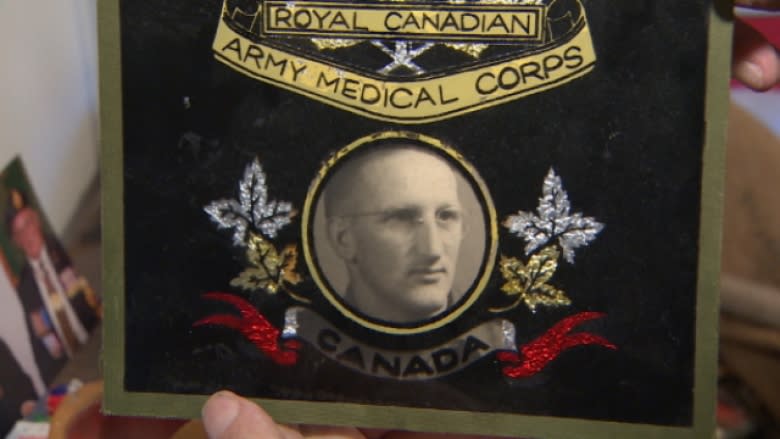

“I didn’t want to shoot my own cousins – that’s why I joined the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps.”

After receiving training in Camrose, Alta., Deutsch shipped out, armed only with a bag of medical supplies.

‘It all comes back to me now’

These days, Deutsch’s Red Deer home is a virtual treasure trove of war history. He has photos of many of the men he served alongside, medals and plaques, and even his original medical kit bag.

Although he can still list the names and dates for every one of the 40 battles he was part of, Deutsch says three battles – Ortona, the Hitler Line and the Savio River – remain the worst in his mind.

“I could tell you story after story all the way through. We broke 40 lines … from the tip of the toe to the Po River and every battle the boys went in, I said 'well, this is going to be your last one and you won’t have to [fight anymore].'

And they just kept pushing them in one battle after another.”

Among the fellow soldiers that he lost, the death of one friend stands out in particular.

“We were together for three days and when we parted … he shook my hand and he said ‘Rudy, I won’t see you again.’ Three days later, I picked him up with a bullet hole through his head on the Hitler Line.”

“Things like that – it all comes back to me now,” he says before pausing.

“I give great honour and regards to the infantry because they took the brunt. When you asked them to take an objective, them boys would go in and take it.

They knew they were going to die, you know, it was terrible to see; these young lads, 17-, 18- and 19-years-old, going in there and fighting for our country.”

Hoping to match that bravery and help the infantry out in whatever way he could, Deutsch says he volunteered for every risky rescue that came up – and has the shrapnel wound to show for it.

“The poor, bloody infantry ... My heart grieved every time they went into action because I knew within an hour or two they’d be blown away or shot or something and we’d be picking them up,” he says

To this day, Deutsch says he still has nightmares of those he wasn’t able to save.

Two boys lost

Of all his experiences in the towns and fields of Italy, it is the uncertain fate of two young boys that appears to weigh most heavily on Deutsch.

After their mother was killed and their father mortally wounded by shelling in their home of Ortona, Deutsch took care of the two children for several days

“Then I had to go back up to regimental aid post so I had to leave them. When I come back in a week’s time, they were gone and I didn’t know where they went.”

When he returned to Italy years later, he tried to find them to no success. But to this day, he holds out hope they will reconnect.

“I’d like to phone them and tell them how their dad died. It was my responsibility.”

An end to war

“When you see so many … lives of innocent people lost, rooted out of their homes and you see that everyday – like I saw for two years – this is why I can’t see anybody going to war anymore,” Deutsch says.

Today, the veteran dreams of a world where peace and freedom reign “instead of throwing some more shells and bombs.”

“This is why people react,” he says. “I don’t think there’s any need for that. Two rights never never make a wrong."

On Remembrance Day, Deutsch says he will think back to the regiment and infantry he was so proud to serve beside.

“I’m thinking of the soldiers like I did when I was overseas … when I saw those poor boys going into action, and knowing they’re not going to come out.”