Is Sarah J Maas the next JK Rowling?

The end of January, just before midnight. At a Barnes & Noble bookshop in New York, a woman with perfect hair slips through a crowd, dressed in all black and knee-high boots. “I grew up going to midnight release parties,” she confesses into her microphone. “I was a nerd back when it was not, like, cool to be a nerd. This was the dark times. This is when you were shoved into a locker or a trash can just for being a nerd. And I love that, now, you guys can be free.” Amassed before her, the emancipated “nerds” scream and whoop, as though in the presence of the messiah. But who is this chicly dressed liberator? Her name is Sarah J Maas, Manhattan-born fantasy author and bona fide publishing phenomenon.

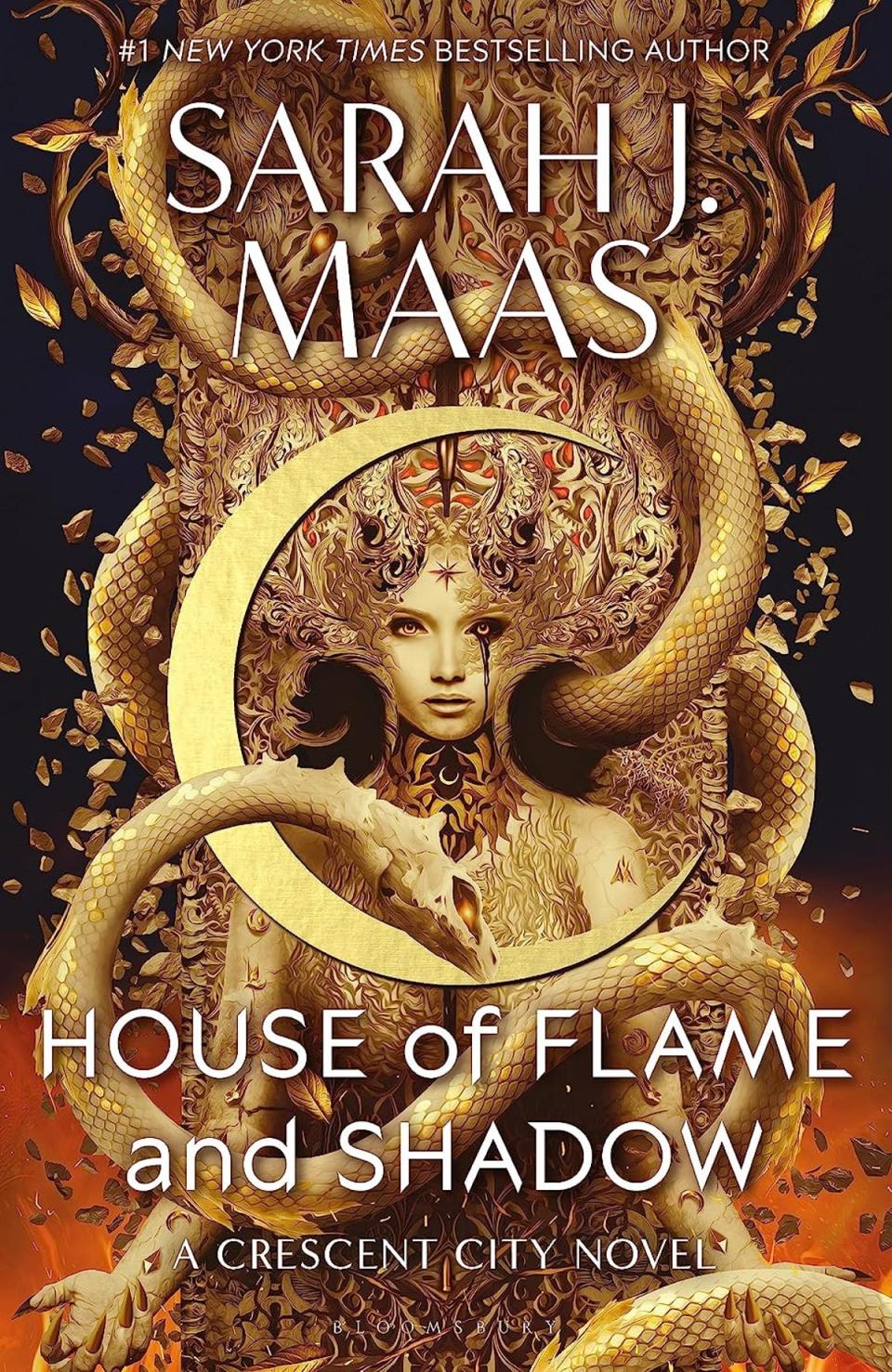

This rock star reception from Maas’s readers has translated into major financial clout for her publishers, Bloomsbury. Earlier this year it announced that the company’s profits are “significantly” ahead of expectations, in large part due to Maas and her exploding global following, news that pushed the publisher’s shares up by more than 9 per cent. House of Flame and Shadow, the book that merited worldwide midnight release parties and is the third instalment in Maas’s raunchy urban Crescent City series, sold 44,761 copies in the UK in its first week, immediately making it the third fastest-selling sci-fi/fantasy book since records began. Maas, a leading force in the “romantasy” genre beloved by BookTok – in which fantasy tales are fused with steamy love stories – has sold nearly 40 million books, while TikTok posts about her work have been viewed over 14 billion times. Make no mistake: her impact on publishing is as tectonic as the orgasms being had by her half-human, half-faerie heroines.

Not since the rise of a speccy boy wizard with a scar on his forehead has Bloomsbury had such a massive hit on its hands. Could Maas be the new JK Rowling? The publisher’s CEO Nigel Newton tried to temper expectations when asked the question (Rowling has sold 600 million books since the first Harry Potter hit shelves in 1997), but couldn’t entirely conceal his excitement. “The bar is extremely high with JK Rowling, so one has to answer that question cautiously,” he told The Times. “All I can say is that the early signs are very good,” with Newton adding that “the signs of lift-off are similar”.

If you never venture onto TikTok and don’t stray into the fantasy section of Waterstones, Bloomsbury’s cheerful business update may be the first you’ve heard of Maas. But the author, 37, is not an overnight success. House of Flame and Shadow is her 16th book, its series the third she’s authored. Educated at the elite Hamilton College, Maas hails from a more comfortable background than Rowling, who was famously a broke single parent who wrote in cafes while her baby slept and needed a £8,000 grant from the Scottish Arts Council to finish book two. Maas began writing her first novel at the age of 16, before publishing it on a fanfiction website where she acquired her first set of devout readers; Bloomsbury picked her up in 2010. The company’s website features an extremely detailed reading guide for her various series’ and worlds, which can seem intimidating at first glance (“publication order” and “reading order” are two different things? No one’s brain works like that, surely).

Essentially, Throne of Glass, Maas’s eight-book first series, began as a feminist spin on Cinderella – what if she wasn’t a poor put-upon servant to her mean family, but an assassin? A Court of Thorns and Roses, or “Acotar” for fans, is a Beauty and the Beast-inspired fantasy romance, in which the archery-loving, Katniss Everdeen-esque heroine Feyre is banished to the horrible faerie lands and must live with a scary (but hot?) man in a mask. (Maas is currently working on a major TV adaptation for Hulu.) And Crescent City, comprised of three (800-plus page) books so far, is a more grown-up series, sweary and full of what’s euphemistically called “spice”. The series’ star is Bryce Quinlan, who is looking to avenge the murder of her friends in the divided kingdom of Midgard.

Maas’s books – described by Richard Osman this week as like “a porny Lord of the Rings” – certainly feel a far cry from the chaste first kiss between Harry and Cho Chang (yes, that really is what Rowling called an Asian character in 2000). And while Rowling’s books were more part of a British tradition of boarding-school tales such as Billy Bunter, with Maas more likely to mention Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Disney princesses as influences, the pair do share similarities.

Both have created worlds full of complicated caste systems, where lands are dominated by status and role, the privileged unmoved by the down at heel. And, notably, both were struck by inspiration on public transport. Rowling was famously on a train gazing out of a window when the idea for Harry Potter “just fell out of nowhere”. Maas happened to be on a plane listening to the soundtrack from the Sandra Bullock space movie Gravity when a climactic scene from what would become Crescent City popped into her head. More effusive and American, Maas said she burst into tears, telling The Bookseller, “I wound up putting my sweatshirt over my head and crouching down in my seat crying.”

And like Rowling, who made Harry an orphan after the painful loss of her own mother from MS, and who created the soul-eating dementors following her struggles with clinical depression, Maas has put her own painful experiences into her work. Having previously discussed her battles with mental health, Maas revealed that a book written during that period, A Court of Silver Flames, is so personal that it’s too difficult for her to reread. Her happy marriage, to Josh Wasserman, with whom she has two kids, seems to inspire her too. “I think I can write about true love because I get to live that every day,” she said this year. (Her fans are invested in this relationship too, sometimes unable to see the boundaries between reality and fiction – a post about her wedding anniversary bears thrilled comments like “[Acotar character] Feysand in real life OMG” while a baby announcement post prompted a fan to ask, “is her onesie a clue to a future book?”)

Maas has been criticised for her writing persona as a “pantser” – someone, basically, who writes by the seat of their pants. It’s something Stephen King is famous for (and perhaps why both he and Maas write chunky – arguably undisciplined – doorstoppers) and Rowling is not, always planning her books out on detailed grids. But while both Maas and Rowling are adored for their characters, storytelling and worldbuilding, both have received flak for their prose.

In 2000, writer Anthony Holden faced the wrath of 11-year-old readers when he lambasted Rowling’s “pedestrian, ungrammatical prose style which has left me with a headache”. For all her other successes, Maas’s prose won’t win her the Pulitzer. “So much colour, so much sunlight and movement and texture… I could hardly drink it in fast enough,” begins one flaccid scene, while one faerie hunk prompts Feyre to note that she “couldn’t ignore the sheer male beauty of that strong jaw”. Certain phrases appear time and time again: “growled”; “barked”; “watery bowels”; “apex of thighs”. The words “vulgar gesture” appear so regularly that there are whole Reddit threads dedicated to understanding what Maas thinks a vulgar gesture is. One fan took it so far that she made a T-shirt emblazoned with “the Maascabulary”. The level of world-building in Crescent City, too, reaches such a height that I needed a Duolingo crash course in Maas-talk just to understand basic elements of the plot. (“Sabine ordered the Scythe Moon Pack to watch Briggs tonight, along with some of the 33rd.” Right…)

These are books, said Vulture, that require the “abandonment of an ironized mind”. But if Maas’s Americanisms can prompt eyerolls – “Only you can decide what breaks you,” says her website – she was ahead of the game when it came to the rising appetite for empowering female heroines. If Lord of the Rings was blokey, and A Game of Thrones was rapey, Maas’s books are notable for a totally different defining factor: female agency. And just think – when Rowling was first getting published for her books in which the main female character is a swotty sidekick, she was advised to use the name “JK Rowling” to disguise her gender so as not to alienate boys.

Much has been made of the amount of sex in Maas’s books (which will sometimes make you giggly – “Isaac took a contraceptive brew,” we’re told of one responsible lothario), but there’s an aspect of this fixation that veers dangerously close into shaming female readers for what they enjoy. As Emily Henry, a bestselling romcom writer also favoured by TikTok, told The Independent, “I feel like it’s a long con that has been going on since before the Victorian era just to convince women that everything about them is a little bit shameful.”

On that Barnes & Noble stage back in January, Maas declared to her legion of fans, “I will never stop being grateful for the courage and the strength that you have given me.” This may be American-speak for “lots of money”. Already there are fans with Maas-related tattoos, Etsy heaves with merch bearing quotes from Maas’s novels, and colouring book editions exist for each series. Could we see blockbuster film series and theme parks, as we have with Rowling’s boy wizard? Will the jargon from Acotar and Crescent City work its way into our lexicon, just like Hogwarts and “muggles”? Perhaps. After all, when the first Harry Potter book turned 25, I foolishly declared that we’d never see the like of its feverish midnight launch parties again. I had no idea a Maas movement was on the rise.