Sask. cancer patients are angry at Premier Scott Moe and the unvaccinated

Andrew Hanna was diagnosed with bladder cancer in the middle of the pandemic last year. He had his surgery in early fall 2020 and was subsequently put on a regimen of treatments.

Now the province has disrupted his treatments due to hospitals being packed with COVID-19 patients.

Hanna, a resident of the Nutana neighbourhood in Saskatoon, was put on a treatment schedule that involved cystoscopy appointments every three months followed by Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) treatment.

"In BCG treatment, they infuse my bladder with live tuberculosis bacteria. For some reason, this works wonders on bladder cancer, so I go in once a week," Hanna said.

The 70-year-old said the BCG treatment hardly takes 15 minutes.

Hanna was also recently put on a six-month schedule where instead of getting scopes done every three months, they would be conducted bi-monthly. But before the transition was complete, his treatment was disrupted. His last scope was on Sept. 24.

"As I walked out the door of the outpatients department that day, they were shutting it down. I was not scheduled to have my next scope and treatments until December. I've already been told they've had to cancel it all and that they have no idea when I'll be getting mine next," he said.

He said his urologist is as in the dark as him on when the treatments will resume, as both the department and unit that were involved in the treatment have been shut down due to nurses being reallocated.

Scott Moe and the unvaccinated are accountable, Hanna says

"I do know that bladder cancer is one of the easier cancers to control and cure, but it's also a cancer with among the highest rates of returning," Hanna said.

He said the wait means he will not be able to get his cystoscopy, which is supposed to reveal whether or not his cancer is spreading. Since that detection is delayed, his treatment for a potential recurrence is also delayed.

"I'm pissed off. I'm angry with the situation. But worrying does no good whatsoever," he said.

Hanna said he has no options but to wait. He can't travel to other provinces or even nearby cities, as his bladder control has been affected.

He said Premier Scott Moe should have paid heed to the modelling data and advice of medical health officers, and not lifted COVID-19 restrictions on July 11.

"The accountability is shared between those that have refused to get a vaccination and Scott Moe. I would just say to Moe to quit posturing and get us out of the situation," he said.

Tim Clarke, a resident of Saskatoon, concurs with that sentiment.

Clarke has a rare form of lymphoma called mycosis fungoides — a disease where white blood cells become cancerous and affect the person's skin. It can lead to rashes and tumours.

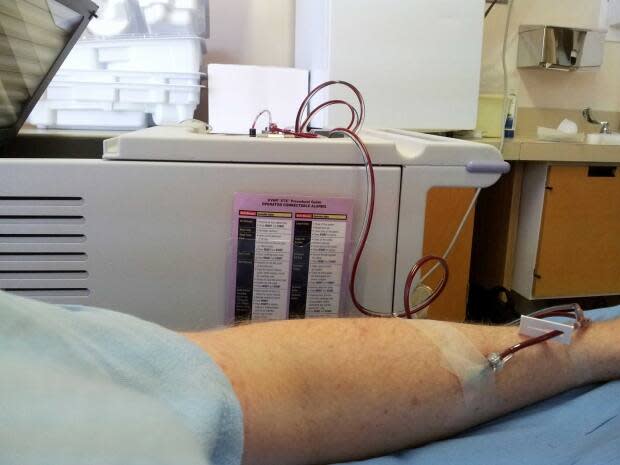

Clarke usually receives photopheresis, a blood-filtering treatment for the condition, every two weeks at the Royal University Hospital.

But his treatment schedule has been disrupted due to the pandemic-induced reallocation of nurses within the hospital. The department that offers the treatment has gone down to only operating one day per week.

Clarke said that the provincial government's approach to the pandemic has "always been late, begrudging and hostile".

"The callousness with which the provincial government has responded to COVID-19 deaths, that were avoidable, is deeply offensive. We're just a rolling major tragedy," Clarke said.

"Our government talks about how restrictions would be unfair to the vaccinated. Well, lack of health care is unfair to the vaccinated."

'Uncertainty is stimulating in the absolute worst possible way': Clarke

Besides receiving photopheresis, Clarke has to take a daily oral medication and inject interferon alfa once a week.

He also receives phototherapy called bathwater PUVA, in which he is soaked in a bath of medication and then exposed to high intensity UVA light to activate it. He also receives cryotherapy for his skin condition.

His photopheresis will operate on reduced capacity until January. He said the department is only open on Wednesdays and all the patients receiving photopheresis are "crammed into one day." Before the pandemic, the department was running three to four days a week.

"If there are any problems, there's no capacity [in present health care] to make up for a mistreatment. I won't die if I miss one or two treatments. If I miss three, then we start getting into sudden changes in my skin," he said.

The 40-year-old said one recent treatment had to be cancelled because he was on antibiotics stemming from a cryotherapy treatment.

He said the strain health-care system is experiencing has impacted the staff too.

"Treatment is a lot more rushed. The experience is a lot more impersonal. Everybody is stressed, it's tangible. In previous times, nurses that I've known for a long period would stop and chat with me for a few minutes. Now, it's very quick, crisp and short," he said.

Clarke said he empathizes with their situation, as due to department shutdowns there is more equipment and patients at RUH.

He is worried that a lack of restrictions could lead to his already disrupted treatment schedule grinding to a halt.

"The uncertainty is stimulating in the absolute worst possible way. The anxiety is appalling. Overlaid through all of it is this incredible disbelief that we have reached this point," he said.

"I'm in the highest risk category. We need temporary measures to buy space in our healthcare system."