Scattered specimens: Why most of P.E.I.'s natural history isn't on the Island

Much of P.E.I.'s natural history isn't on display on the Island for people to learn about, let alone use for research.

It's something many would like to see changed — with the addition of a provincial museum.

An inventory of natural science specimens published back in 2014 showed just how far and wide P.E.I.'s specimens have been dispersed over the years.

For example, 7 per cent of the Island's collected and catalogued animals and plants are in institutions in the United States — while only 5 per cent are on P.E.I.

The P.E.I. Museum and Heritage Foundation reports that about 30 museums and institutions in Canada and 20 in the United States have P.E.I. specimens.

Rosemary Curley, former president of Nature P.E.I., said it's felt like the province's natural history just hasn't been considered important enough to gather in one place on the Island itself.

"All other provinces and territories have museums, and they do have collections of natural history specimens ... and they prepared displays on them so people can learn about them," she said.

"There were naturalists around 1900 to 1910 who asked to have a natural history museum. But nothing ever happened. They actually asked to be able to store specimens at the legislature."

The foundation does operate a number of smaller museums across the Island, which focus on specific areas or industries.

Other specimens are in storage. There are also other museums run by communities and not-for-profit groups.

Curley said it's unfortunate that very few natural history specimens are on the Island.

"If we want to know about our wildlife, we have to ask other museums what they've got and what they've identified," she said.

"It seems to be a difficult proposition to actually get to a new museum, and I'm not sure why that is. I think we're just undervaluing our past, our historical past and our history of species on the Island. For some reason, we're just not pulling it together."

Island specimens found 'all over the world'

Fiep de Bie put together the 2014 inventory of natural science specimens found in P.E.I.

As part of that work, she visited a number of places in the Maritimes that have Island specimens.

"The rest I basically went online," she said. "Not all the information is digitized yet, but there are lots of portals and databases, search engines, to find those specimens from P.E.I. And they're all, of course, associated with different museums all over the world, but a lot in the United States."

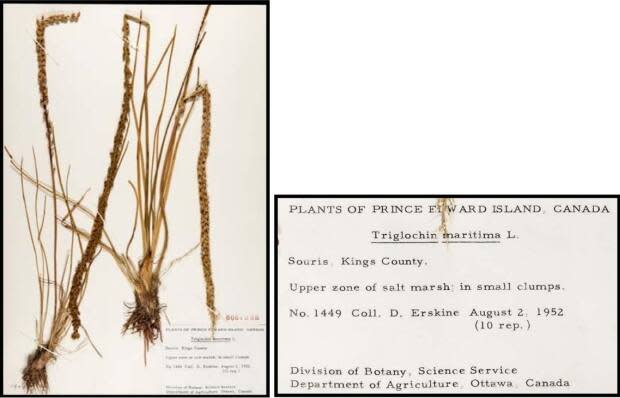

De Bie ended up finding about 40,000 specimens. Among them are 48 plant records at Harvard University, some of which were collected as far back as 1888.

The Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard has 114 records of snails, slugs and clams collected between 1972 and 1973 in places such as Darnley and Miscouche.

Then, there are the specimens that live at the Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, England.

De Bie's inventory said the gardens hold "what is known as the earliest P.E.I. botany collection, which was deposited by Miss Margaret Grubbe in 1944. The specimens were collected between 1849 and 1854 by Miss Grubbe's great-grandaunt, Ann Elizabeth Grubb-Haviland, wife of Father of Confederation, Thomas Heath Haviland Jr."

A dimetrodon fossil named "Leidy" that was found in 1845 in French River was donated to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in 1854.

A Sowerby's beaked whale that was stranded at MacNeill's Brook, near Cavendish in 2013 is part of the New Brunswick Museum collection.

De Bie said it's important to know about natural history of a place over time, to see how things change.

It's very important to understand the past, the present and what maybe predicts a little bit the future about these ecological specimens and their environments. - Fiep de Bie

"Especially now, everything is changing so much and the distribution of animals and where they now live and climate change has an impact on that. And it's very important to understand the past, the present and what maybe predicts a little bit the future about these ecological specimens and their environments," she said.

"So maybe we need to do a report in another whatever number of years or so to see what's what."

Keeping history in one place

De Bie said having a museum might entice people to collect more specimens on P.E.I.

"I think there will always be people interested in natural history, but it's also nice to be able to deposit them somewhere so that people can see them as well, and learn from them. So you can have visitors or educators that can go to a place and see them. And perhaps also have more researchers look into other species that can be researched," she said.

"It would be ideal to have a museum in general and then maybe a section with natural history."

She said as a Museum and Heritage Foundation board member, she knows the idea of a curator of natural history has been floated in the past.

But government hasn't allocated any funding for the position.

"I know right now some of the natural history specimens are on display, but they're in the different museums, which is also a good thing, you know? But it would also be nice to have it more elaborate and have more specimens and research possibilities in one place," she said.

De Bie said she learned a lot about P.E.I. from putting together the inventory.

"A lot of awareness of where everything is and how many people actually did come to the Island to study. From fish to mosses to vascular plants to mollusks."

"We have to keep on collecting and learning from nature and if it's needed to do a report again."

Bob Harding is one of many Islanders who has contributed to P.E.I.'s natural history. He began collecting dragonflies with his kids in the '90s.

"It became a family event for us in the summer time and a great opportunity to get outside and appreciate nature and make a contribution to the body of knowledge, I guess," he said.

'For a hundred years or more'

Most of the family's specimens at being kept at the New Brunswick Museum.

"It would have been a lot nicer to be able to leave them here. The only reason they didn't stay in Prince Edward Island is because they would be in my attic. And if something happened to me or to our house, they'd be gone forever. So this was a way to actually make sure that they could be there for review and for study in a hundred years or more," he said.

"If we had somebody that was a natural history curator who had an opportunity to understand what we have in Natural History and Prince Edward Island and places where these specimens could be appropriately stored, that'd be a real win for P.E.I. We're missing that as a province, in my opinion."

Harding said it's all about scale, and doesn't know if P.E.I. would need a museum the same size as other places.

"Perhaps we should have something smaller. But right now, we don't have something smaller. We don't have anything," he said.

He tells the story of how a curator at the New Brunswick Museum once showed Harding and his kids a dozen passenger pigeons in a little drawer.

"Now, they've been extinct for over a hundred years. That's pretty impressive. And here they are ... Somebody a hundred and some years ago thought about we should save some of these so that we can actually do some research on them," Harding said.

"It's not just things that people are collecting now, it's things that are gone now that nobody can actually access ... Once something's gone, it's too late to learn about it."