School closures will turn villages into ghost towns, rural residents warn

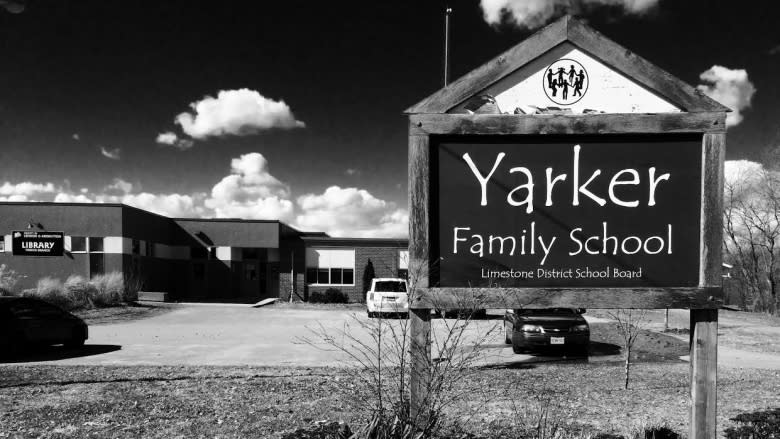

Yarker, Ont., is a picture postcard of rural life, complete with a tiny village school.

It's Jill Kilgour's hometown. She moved back here about three years ago, hoping to send her young children to the same school she attended.

That dream may soon disappear. The student population of Yarker Family School has shrunk to just 26 junior kindergarten to Grade 3 kids, one-third of the of the school's capacity.

So like hundreds of schools across the province — many in rural communities — Yarker's is at risk of closing, and Kilgour fears that could mean arduous bus rides for her small children.

"I have four children under five," Kilgour said. "Where am I going to send them? If Yarker school was to close, they would be going a minimum of half an hour, but probably more like an hour on the bus."

Fearing wave of closures

People throughout Stone Mills Township, a municipality of 7,700 northwest of Kingston, worry shutting down Yarker Family School could trigger a wave of school closures.

While Yarker's school is the only one in the township currently under review, the Limestone District School Board's long-term pupil accommodation plan recommends reviewing the other four — all under-enrolled — next year.

Trustees must vote to trigger reviews, as they did for Yarker Family School.

"This school has been the heart of our community for over 150 years," Kilgour said. "It would really be a shame to see our heart stop beating here."

Dire economic impact

Local councillors hired consulting firm Doyletech to assess the economic impact of closing all of the Limestone board's schools in the township. Its report predicts a drain of $3.2 million a year from the local economy, an amount equal to more than half the township's annual budget.

Robin Hutcheon, who lives in the village of Tamworth, predicts the real cost would be the very existence of Stone Mills.

"I think you'd be looking at a whole lot of ghost towns around here, because you'd gradually see the population get older and older, because young families would not move out to these areas. Eventually they would just shut down."

Lindsay McDougall, who moved to Yarker from downtown Toronto in 2010, said if trustees vote to close the school, she and her husband and two children will consider moving to Kingston in order to remain within walking distance of a school.

"It's a real mismatch that on the one hand we're trying to promote physical fitness and outdoor activity, to then be recommending our kids spend hours a day on a bus," she said.

Hundreds of schools at risk

People in rural communities across the province have similar concerns.

The Upper Canada District School Board voted last week to close 12 schools in small communities in eastern Ontario.

It's happening after the government scaled back grants for rural schools while maintaining a per-pupil funding formula that encourages school consolidation.

Creative solutions to keep schools open don't seem to be working.

Parents in the Township of South Stormont recently managed to find a corporate sponsorship worth $400,000 to help save Rothwell-Osnabruck High School. In the end, the Upper Canada District School Board voted to close the school anyway.

In Yarker, ideas to boost enrolment have included adjusting the school's catchment area and adding special programs such as outdoor education.

But parents complain the exhausting task of coming up with options has been left to them. They say they've had limited support from the board, which is required by the province to pick a "preferred option" at the outset of any school review.

In the case of Yarker, the board's preferred option is closure.

"They just want to shut the schools down because it is the easiest thing to do," Kilgour said. "We believe in fixing what is broken. We are fixers in the rural community."

Closing the school would also mean abandoning a new classroom that was built recently to accommodate full-day kindergarten. The province paid nearly $700,000 for the addition, but enrolment still dropped. The school's old kindergarten classroom now sits empty.

'This is anti-rural'

School board officials say reviewing schools for closure is painful for both the community and board staff.

"Certainly we understand that any changes that may come from this process would be felt most deeply by our students and the families of those in the affected schools," said Alison McDonnell, chair of the committee for the review of Yarker Family School.

"We need to take into consideration their concerns, but also balance the issue of declining enrolment in our board and also look at reducing the financial liability of the board."

Much of the anger in Stone Mills is directed not at the school board, but at Queen's Park.

"As soon as the funding got changed, whereby the boards don't raise their own money the same way, the power went to Queen's Park," said Wayne Goodyer, a retired teacher who helped in a successful fight to save Yarker's school in the 1970s.

Goodyer has little appetite for the argument that half-empty schools are a luxury Ontario can't afford. He says the province needs a fair, comprehensive rural schools policy.

"We're not cabbages. You can't simply take a geographic area and say, 'You know, all those schools are half-full. Maybe they'd all feed this one 20 miles away.

"This is anti-rural. This is exactly the thinking we're confronting: 'Well why don't you people move to the city?' Well, because we were here before you were. There has been a school in this little village for 170 years."