Secret murder: A tale of two police forces in Alberta

Two years ago, the Alberta RCMP quietly stopped naming victims in many homicide cases.

At the time, an RCMP spokesperson said their policy was to reveal the names "only after the immediate family has no objection."

Now it appears that policy has been quietly reversed.

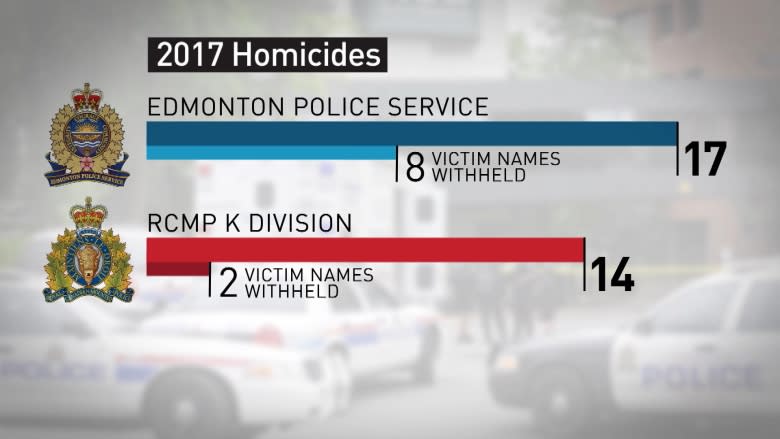

Sgt. Jack Poitras said the RCMP's K Division in Alberta has handled 14 homicides so far this year, and they have identified the victims in all but two of those cases. He called it an issue of transparency.

"Actually I've been trying to get the names out there when we can," Poitras said. "I know we have to work with the federal Privacy Act. But when we're able to, especially on homicides where a lot of times the community wants to know what's going on, we try to get those names out there. It's a concern for the citizens when heinous crimes occur that they are informed and they're aware."

Poitras points to the section of federal legislation that essentially states a person's privacy is not protected when it refers to personal information that is publicly available. He acknowledged that once criminal charges are laid, the victim's name is part of the publicly accessible court record.

Edmonton police service going in opposite direction

At the same time as the RCMP in Alberta began to regularly release names in homicide cases, the Edmonton Police Service was increasingly withholding victims' names. The practice appeared to begin with a murder-suicide case in mid-January. EPS refused to name the man and woman involved in that case.

There is a standard explanation at the bottom of all Edmonton police news releases when names are not released that reads, "Every file is evaluated on a case by case basis. The EPS has decided not to release the name of the deceased in this investigation for the following reasons: it does not serve an investigative purpose, there is no risk to public safety and the EPS has a duty to protect the privacy rights of the victims and their families."

There have been 17 homicides so far this year in Edmonton and police have refused to release names in eight of those cases.

"We absolutely want to be open and transparent," Edmonton police Chief Rod Knecht said in a recent interview. "We want to give the public and the community and everybody as much as we can."

But he said respecting the wishes of the victims takes top priority.

"When we are holding back, sometimes it's because the victims have asked us to hold back," Knecht said. "Our critical focus is on the victims. Making sure the victims aren't re-victimized."

Knecht insisted the department's default position is to be as open as possible.

"We will always default to putting the name out," he said. "Internally we ask, why would we hold back the name? And if we don't have a good reason for that, the name goes out."

Names withheld in four of five Edmonton homicides in April

The name of the city's most recent homicide victim was released by Edmonton police on Monday.

They say Jake Myles Skrepnek-Rey was stabbed to death. A police spokesperson said the decision was made to release the name for investigative reasons. Detectives believe at least four other people may have witnessed the stabbing, and police would like to speak to them.

But when Kathy Dickout was killed in her own home, allegedly by her son, police refused to name her.

When the city was gripped by the tragic death of 19-month-old Anthony Raine, police refused to identify the victim. Even though CBC News had already interviewed the toddler's mother and the family had launched a GoFundMe page.

Brandon Provencher was stabbed outside an LRT station last month. By the time second-degree murder charges were laid, the 19 year old had already been identified by many media outlets, through social media posts and on a GoFundMe page.

Dustin Horsethief died on April 22, after being pulled off life support following a machete attack. The 34 year old's obituary was in the newspaper and his family launched a GoFundMe page and a memorial Facebook page.

Knecht said lawyers are often involved with the decision about whether to name homicide victims. But he said the final decision rests with officers

"At the end of the day, the lawyers give us their legal opinion," Knecht said, "and it's up to managers or myself as chief to make the decision."