Short on SC certified teachers, Richland 1 students are teaching themselves, parents say

In late August, nearly two weeks into the school year, Ashley Jaillette and dozens of other A.C. Flora High School parents received a blanket email that their children were enrolled in classes that didn’t have teachers.

The communication, signed by the school’s principal, expressed optimism that the vacancies would soon be filled and assured parents that, while not ideal, students would receive “meaningful instruction” until a qualified teacher was found.

In many cases, parents said that didn’t happen. Vacancies persisted for months or were never filled as teacherless classrooms cycled through a series of substitute teachers who monitored students working on tedious online assignments or simply killing time on their cell phones.

“They have a long-term sub in the classroom, but that person is basically just to make sure that they’re sitting there doing what they’re supposed to and no fights break out,” said Jaillette, whose twin sons both began the year without teachers in one of their classes.

As South Carolina’s teacher shortage intensifies — there were a record 1,613 vacancies statewide at the beginning of the 2023-2024 school year, according to the Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention and Advancement — more students are winding up in classrooms without certified teachers.

That matters, experts say, because a lack of qualified teachers threatens student learning and puts an even greater burden on existing educators, exacerbating burnout and increasing the likelihood that more teachers leave the classroom.

“It’s really easy to look at 1,600 vacant teaching positions and see that number in the abstract,” said Patrick Kelly, a lobbyist for the Palmetto State Teachers Association. “But in the concrete, it has real implications for students and for school staff.”

Those implications are felt more acutely in some districts than others, including Richland 1, which has relied heavily on substitutes and online learning amid struggles to recruit and retain teachers.

Since 2021, teacher vacancies in Richland 1 have more than quadrupled and the district’s teacher turnover rate has soared to 22.5%, higher than similarly sized districts in South Carolina, according to CERRA.

The 22,000-student district reported a state-leading 177.5 vacancies to start the year, according to CERRA, and was advertising 224 teacher openings on its online job board, as of May 7.

“Everybody has a kid who either knows somebody or themselves doesn’t have a teacher in school,” Richland 1 board member Robert Lominack said during a meeting last year.

For months, Lominack, a former Dreher High School Latin teacher and critic of the current administration, has unsuccessfully sought information from the district about the number of students who have gone without a certified teacher this year.

Richland 1 human resources director John Koumas and coordinator of recruitment and retention Felicia Richardson declined to disclose how many classes had been covered by long-term substitutes this year, but cautioned against reading too much into CERRA’s numbers or trying to extrapolate vacancies from the number of job openings being advertised on the district’s recruitment website.

“I think it’s important to remember that the situation that Richland 1 is in is not unique to Richland 1,” Richardson said. “There are schools across our state and across our nation that are suffering from the same type of shortage that we have. So we kind of have to put it in perspective.”

Many community members aren’t satisfied with Richland 1’s response to the teacher shortage, however, and said the administration’s obfuscation and apparent lack of a coherent strategy to address its recruitment and retention problems are unacceptable.

They fear the district’s failure to make contingency plans, best exemplified by its controversial mid-year reassignment of 11 teachers last October, could result in a repeat scenario come fall.

“Their failure to plan constitutes an emergency,” said Scott Barber, an A.C. Flora parent who regularly speaks at district board meetings. “And because they couldn’t plan for how many teachers they needed or they couldn’t recruit them because of their policies and lack of supporting teachers, people are leaving.”

While reversing the district’s teacher shortage is possible, Richland 1 board member Barbara Weston said, it must start with a recognition of the problem.

Rather than viewing the district’s situation as symptomatic of a national issue over which it has little control, Lominack said the board and administration need to take more seriously the district’s ongoing exodus of experienced educators.

“I think we’ve turned a blind eye to things we could have done to keep as many teachers as possible, understanding that all districts are in a tough spot,” he said.

‘I wanted a teacher’

When COVID hit in 2020, Ashley Jaillette moved her sons out of Richland 1 and into a private school that offered face-to-face instruction.

She assumed by the time they returned to the district this school year, as freshmen at A.C. Flora, things would be back to normal.

But Jaillette was in for a rude awakening.

Unbeknownst to her, one son started the year without a web design teacher and the other lacked an earth science instructor. A non-traditional teacher working toward his certification eventually took over the web design class, but the science vacancy still has not been filled.

“I just told him he’s going to have to grin and bear it at this point,” Jaillette said.

Richland 1 plugs vacancies in a variety of ways, including by combining classes, reassigning certified teachers and contracting with private virtual instructors. Oftentimes, however, parents of high school students said their children are simply assigned online modules to complete in the presence of a substitute teacher.

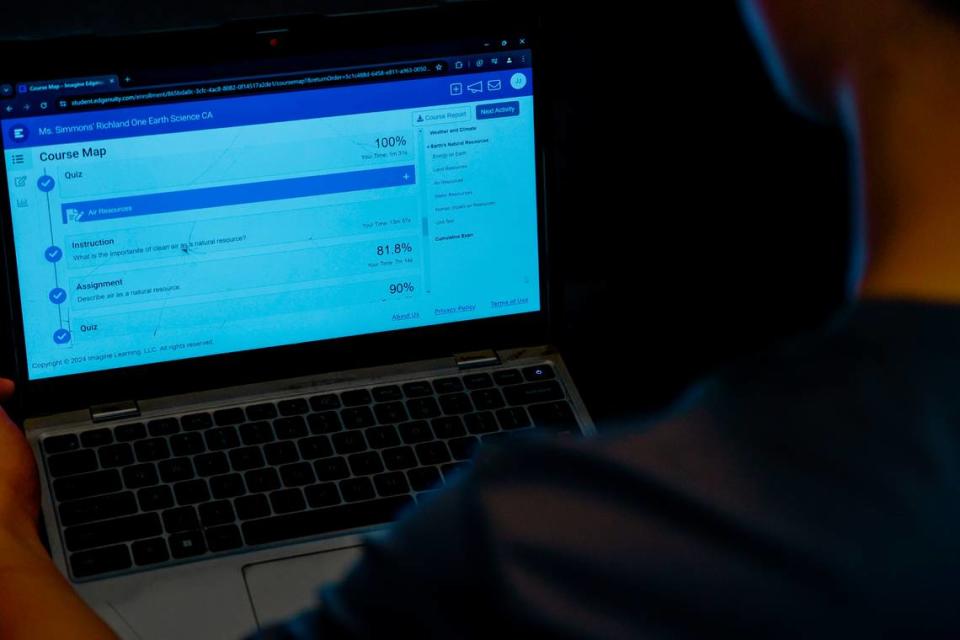

“They gave us a site called Edgenuity, which was an online platform,” one of Jaillette’s sons explained. “They wouldn’t teach us anything, they would just make us do that. We had to get to a certain percentage done with it and that would be the grade put in.”

Many students do the bare minimum, he said, because there is no one to ask for help. Others resort to cheating due to the lax oversight of the self-paced modules, according to interviews with multiple students, parents and teachers who requested anonymity to speak freely.

Originally billed as a credit recovery tool for students who failed classes or needed extra practice in a subject, Edgenuity exploded in popularity during the pandemic and is increasingly being used as a vehicle for primary virtual instruction in districts short on teachers.

The company did not respond to a request for comment, but its vice president for instructional design and learning science told NBC News several years ago that Edgenuity wasn’t designed to be used without live teacher involvement, as parents and students say Richland 1 deploys it.

Kevin Hasinger, Richland 1’s executive director of secondary education, said he didn’t have data on the number of students who use Edgenuity for credit accrual, but claimed it was rare and typically reserved for students who return to school after dropping out or being incarcerated.

He acknowledged it was occasionally used as a last resort for classes with teacher vacancies, but said in those instances there is always a cooperating teacher assigned to support students and an assistant principal who monitors student progress and student understanding.

“There truly is no replacement for a certified teacher,” Hasinger said. “But to that end, we have found that the Edgenuity system is quite successful in preparing students to find success in courses.”

At least nine courses at A.C. Flora High School, including several math and science classes, used Edgenuity for credit accrual for at least a portion of the school year, according to emails obtained by The State newspaper. The prevalence of the online platform’s use in other Richland 1 schools is not clear, but Flora is not unique in terms of its teacher vacancies.

Several parents of students enrolled in Edgenuity classes at Flora said that, contrary to the district’s claims, support for users was inadequate and, as a result, many families had resorted to hiring private tutors for their children.

Jaillette said she emailed school administrators seeking Edgenuity alternatives for her sons, who are dyslexic and struggle with online learning, but got nowhere. While sympathetic to her children’s plight, Jaillette said administrators seemed to have their hands tied.

“I hate it that I returned them back to public school three years later thinking that they would have teachers again,” she said. “And then we’re still kind of in the same boat.”

Students without teachers seek outside help

Several parents, particularly ones with children who lacked teachers in core or foundational subjects, expressed concerns about the long-term impacts on learning.

“As each day progresses, there’s an inequity in the school being created where there are students who had a teacher and are progressing and students who don’t have a teacher and are being managed,” said a Richland 1 parent who requested anonymity.

Her son, she said, spent the first nine weeks of the school year without a Spanish teacher.

After roughly seven weeks of what she described as students being “in limbo,” without any effort made to teach them, they were told to complete a scaled-down version of the class in Edgenuity over the final two weeks of the term.

“The assignment was not representative of nine weeks of Spanish learning,” she said “It was something to count as a grade.”

Her son completed the work and received an A in the class. But when an actual Spanish instructor took over the course in the second quarter, his grades dropped and it became clear he didn’t actually know the material.

“As a family, we had to kind of assess the situation and we came to the conclusion that my son really did need a tutor,” the parent said. “We are able to do that, but not everyone is.”

Kristie Jones, a former Richland 1 teacher who now runs an educational consulting and private tutoring business in Columbia, said she serves more kids coming out of empty classrooms than she used to.

“It seems to me that the number of empty classrooms is growing each year in the schools,” she said. “It seems also that they have them just on an online program.”

While students who lack certified teachers don’t make up the bulk of her customers, Jones said there’s no question the teacher shortage has contributed to the growing need for tutoring support.

Like many educators, she worries about the long-term effects of students coasting through online classes without actually learning the material.

“You put a hall monitor in a classroom with the kids, I’m not sure they’re getting anything out of it,” Jones said.

The parent whose son didn’t have a Spanish teacher during the first quarter said the lack of instruction in building block courses really puts students at a disadvantage.

She said she’d asked about dropping her son back a level in Spanish so he could improve his base of knowledge, but an administrator told her not to worry. The school would get him up to speed.

“They just want you to believe that they’re being taken care of and everything is OK,” the parent said. “But the truth is, what are we asking of the teachers and the students? That’s a lot for kids and teachers to be asked.”

Parents ask district for a plan

Many of the parents whose children lack certified teachers said they realize the state’s teacher shortage puts Richland 1 in a tough spot, but believe the district could do a better job planning for vacancies, communicating with parents and supporting students who don’t have teachers.

“We have all these emergency plans for a fire or an active shooter or a tornado drill,” said the parent whose son started the year without a certified Spanish teacher. “But there’s not an emergency plan for a teacher vacancy, and sadly, that is a very likely scenario.”

Rather than learning their children didn’t have a teacher from a form letter sent two weeks into the school year, after the class withdrawal deadline had passed, she said parents should be notified in advance if a vacancy is imminent and given clear instructions about what to expect.

How will the vacancy be covered? What is expected of students? How will they be graded? What additional resources will they be afforded? How often will school administrators check in and provide updates?

“I appreciate that we can’t do a lot about the economy and that teachers need to make more money,” the parent said. “But what we can do is manage the situation that we have as professionally and thoughtfully as possible, and that’s where it’s frustrating.”

Members of Richland 1’s human resources team told The State they’d heard parents’ concerns and were working on solutions, but couldn’t share any specifics at this time because the details were still being worked out.

The big focus going forward, said Koumas, who started with the district in mid-March, is teacher retention.

“We need to find those initiatives, those means in which we can keep these folks in our district,” he said. “We want the best qualified person in front of our students. They deserve it.”

When asked whether he had anything specific in mind in that regard, Koumas paused.

“I need a little time to see, and like I said earlier, to assess where Richland 1 is right now,” he said.