Space suits, simulations and 'animal fear': How astronaut David Saint-Jacques is preparing for orbit

Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques will launch from Kazakhstan on his first mission to the International Space Station in November, and he's in the final stages of a gruelling training program to get his mind and body ready.

"It's all challenging, because all these training sessions, they represent things that I must know and I must master. Not to try to please an instructor or to pass a test, I must know them if I want to survive," Saint-Jacques told CBC News.

"That added sense of reality, of urgency, of this kind of animal fear, is what drives me to really focus."

It's been a little over five years since the last Canadian Space Agency astronaut, Chris Hadfield, went into space. His "long duration" stay on the International Space Station in 2012-13 lasted about five months.

Saint-Jacques will be in space even longer. Expedition 58/59 will mean a six month stay, alongside NASA astronaut Anne McClain and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Konenenko (with whom Saint-Jacques will be co-piloting the Soyuz MS-11 spacecraft).

The 48-year-old family doctor, former astrophysicist, engineer and father of three from Saint-Lambert, Que., has been doing a lot of work to get ready for the mission of a lifetime.

It's been almost nine years of preparation since Saint-Jacques was selected as a Canadian astronaut, and in the months leading up to his launch on Nov. 15, he is now into the practical stages of training. Saint-Jacques and his family are living in Houston full-time while he spends about 45 hours a week learning everything he can about the station, as well as how to live and work in space.

CBC News got a first-hand look at some of Saint-Jacques' training recently at NASA's Johnson Space Centre in Houston:

In Photos: Space station training

Learning about Destiny

Before going into orbit, astronauts practice working in life-sized models of the International Space Station's nodes. They're located in the Space Vehicle Mock-up Facility at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Here, Saint-Jacques is being asked questions and tested on his knowledge of the workings of the Destiny module. It's the primary research laboratory used for scientific and medical experiments on humans while in space.

During his six-month mission he'll also be responsible for things like maintaining the Columbus Lab, running experiments in the Unity lab, and operating the Canadarm.

Technology and people

There are several dozen people at NASA involved in Saint-Jacques' training, teaching him everything from how to live in space to how to run specific space station systems.

Here, Saint-Jacques talks to a group of NASA engineers about ways to control the temperature onboard the ISS to keep it comfortable for the astronauts during the mission.

Training challenges

While understanding the Soyuz and ISS technology is important, a big part of the training is also about understanding and working with other people.

"The vast majority of problems people ever have in space flights are based on human relationships and communication," Saint-Jacques says.

"So you have to feel ready for that aspect, you're not just there to push buttons."

EMU

The Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) is a suit used at the International Space Station for space walks. It's an extremely complicated piece of equipment with its own life support system that can keep an astronaut alive outside the station for hours during a mission project or emergency.

The suit weighs roughly 50 kilograms. Getting dressed takes about 45 minutes, and putting one on requires the help of another astronaut.

Canadian Jeremy Hansen, right, helps Saint-Jacques suit up before he is lowered into the practice pool at NASA's Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory.

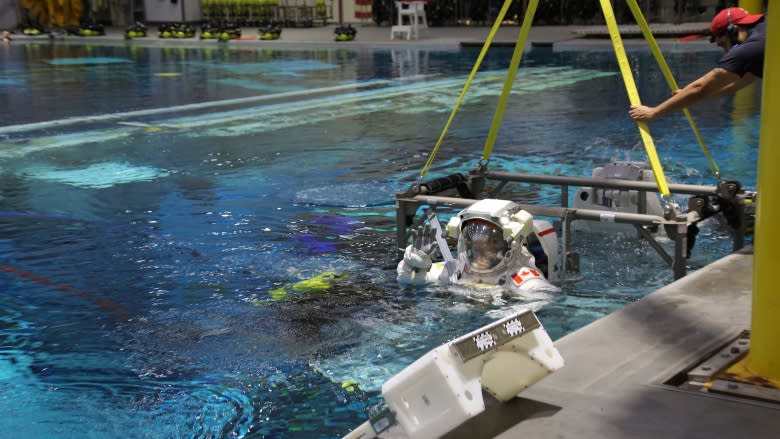

Neutral Buoyancy Lab

The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory is an underwater training facility. The pool helps simulate a zero-gravity and airless environment.

This is where astronauts train in the EMU suits on full-size underwater mock-ups of the International Space Station, so they're ready if they have to use the suits in space for missions, emergencies, or unexpected repairs.

Pool sessions

The bulky suits get even stiffer and more awkward when they're pressurized. Saint-Jacques does regular sessions in the pool so that he's familiar with how it feels to move around and work in the EMU.

Everything he does in the pool is assessed by a team of scientists, but Saint-Jacques also sets his own training goals.

"As we often say, one is kind of one's [own] worst judge, most severe judge. This applies to this training," he says. "I always raise the bar for myself. I just relentlessly raise the bar and raise the bar, to try and maximize my readiness."

ARGOS

The Active Response Gravity Offload System (ARGOS) is a training system designed to simulate low-gravity environments. This helps the astronaut get comfortable with the sensation created by little or no gravity before they head to the space station.

The harness and series of cables may look primitive, but they're connected to sensors and a complex system that helps mimic the feel of working in space.

"It's a feeling that your body is not used to. We're always used to having gravity or a wall or the floor to push against, counteract against," Saint-Jacques says.

"One of the things about space flights is the absence of that gravity. You're floating around, but it's not like floating in water ... in water you can cheat, you can swim. So we train on ARGOS."

Seen here, Saint-Jacques demonstrates carefully controlled movements on the crane-like ARGOS, while working with his hands. He's learning how the simple movements people are used to making in gravity can have unintended consequences in space, pushing your body away from what you're working with or trying to hold on to.

Zero-gravity gym

The lack of gravity also creates potential health problems. While in space, astronauts must exercise 2.5 hours a day, six days a week to prevent bone and muscle loss.

The exercise gear they use is specifically designed for zero gravity and is quite different from regular fitness equipment, so Saint-Jacques needs to learn how to use it before he leaves Earth.

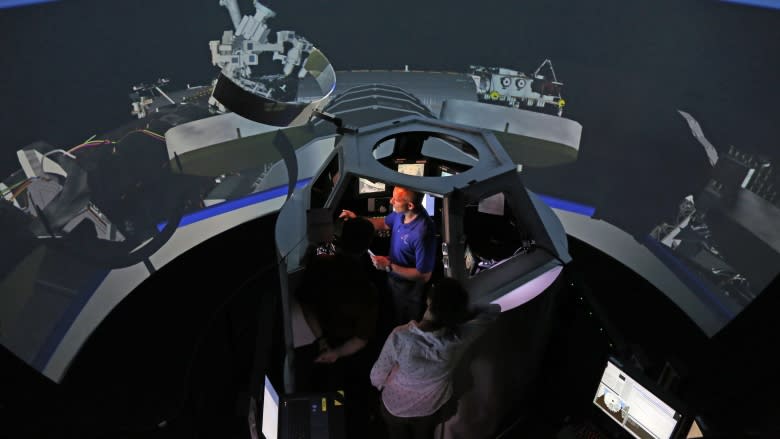

Cupola

The Cupola is like a control tower for the International Space Station. It's a domed-shaped module with windows where astronauts can see the outside of the ISS.

This is where astronauts control the Canadarm 2, observe spacewalks and check out a great view of the stars from 400 kilometres above Earth.

"You get into a zone," says Saint-Jacques, describing how the astronauts focus so intently on the simulations that they feel real.

"You make an effort to put yourself there, and you say 'today I'm really in the Cupola in the space station. And I'm really about to capture a spacecraft worth several hundreds of millions of dollars, and with the whole world watching I must not screw this up.'"

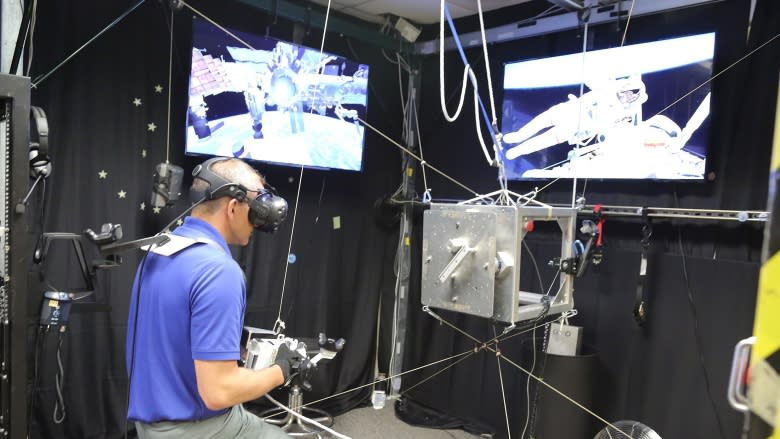

Virtual reality

Virtual Reality technology has become an important part of astronaut preparation. Here Saint-Jacques is training on a system that uses both graphics and motion simulators.

This helps him learn not just the proper physical motions to get a job done, but also feel the sensation of handling robotics like the Canadarm 2 to move material throughout the International Space Station, assemble gear and accept cargo deliveries in space.

A complicating factor is that there's only so much that Earth-based training and simulations can do to prepare him for the realities of extended time in orbit.

"All this virtual training that we do — spaceflight is one of those things you cannot train for real, you have to fake it. You have to play astronaut all the time, and it only works if you make an effort to believe in it," Saint-Jacques says.

Mission Control

Right now, Saint-Jacques has direct access to NASA instructors when he has problems and questions.

"There's a self-imposed tension, that this may be my last chance to train on this, the last time that I have a structural expert there to answer this question on this topic," he says. "There's a sense of urgency, and the nearer and nearer you get to the launch, the more and more responsible you feel for your own training, and the more you realize that at the end of the day it's just between you and yourself whether you're really ready."

When he heads into orbit in November, Saint-Jacques will still be able to communicate with NASA's experts, but it will happen via radio to Mission Control in Houston.

This is the room from which Saint-Jacques and his colleagues will be monitored at all times during their six-month stay on the ISS. Mission Control is staffed with flight controllers 24/7.

The magic of spaceflight

While he's focused on the physical and mental preparation for his November launch and mission aboard the ISS, Saint-Jacques says he hasn't lost sight of the "magic" of spaceflight.

"On the one hand it is a technological wonderland. It is the apex of human ingenuity and creativity," he says. "It does draw the best out of the human imagination. There's a huge amount of science being developed there, especially medical science that's going to have a huge impact for everybody on Earth.

"But then there's other aspects ... there's the incredible miracle of international collaboration that it represents. And especially in this day and age, we should never forget that the space station was built by 16 nations, the four biggest contributors being the United States, Russia, Germany and Japan," he adds, pointing out that there was a time not long ago when there was "very little collaboration" between these nations.

"So space does that — it is one of those arenas where humans play well together and honestly want to achieve the same goals."

- WATCH: The National's Ian Hanomansing follows David Saint-Jacques through NASA's International Space Station training program