Suicide rates are highest for men in their 50s and we're not sure why

Men take their own lives at about four times the rate women do, a number the Movember Foundation highlights this month in its campaign around men's mental health.

In Canada and the U.S., the highest suicide rates are among men in their 50s (except for men over 75 in the U.S.).

But we're not sure why.

There's rarely just one factor that explains an individual suicide, and that's likely so for suicide rates.

Part of the explanation for the high rate among men in their 50s includes the reasons men generally have a much higher suicide rate than women. But then what are the reasons for so many suicides by men in their 50s, and why has that rate gone up faster than for other age groups?

For Vancouver psychologist Dan Bilsker, what's striking is how little we really understand about why the numbers peak when men are in their 50s. "It doesn't fit previous models of things driving suicidal behaviour."

In those models, by their 50s, men should "be feeling more in control of their lives, have worked out a lot of issues, be coping pretty well," he says. After all, most of them are working, they've had jobs, relationships, children, life experiences. So the high suicide rate "raises a more disturbing model."

Bilsker has talked to thousands of people who were at risk of suicide. He now teaches at Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia.

Coping skills fall apart

Dan Reidenberg also has lots of professional experience with suicide, and lots of questions about the high rate for men in their 50s. Based in Minnesota, Reidenberg is executive director of Suicide Awareness Voices of Education and managing director at the National Council for Suicide Prevention.

"What is causing the coping skills to fall apart and not work the way they did before?" he wonders, emphasizing the need to understand why.

Both experts say part of the problem is how little research has been done to try to understand the high suicide rate, and that middle-aged-male suicide has not been the priority it should, given the numbers, especially the number of years of potential life lost (for men, suicide ranks second, after unintentional injuries).

In Canada, the U.S. and the U.K., experts point to the recent economic crisis as leading to an increase in suicide rates, although the relationship is complicated.

While the overall U.S. suicide rate increased by 15 per cent from 1999 to 2010, the rate for men 50-59 went up 49 per cent. The latest figures, for 2013, show that the rate has changed little since 2010, at about 30.5 suicides per 100,000 for men in their 50s.

A recent study, co-authored by this year's winner of the Nobel Prize for economics, Angus Deaton, found that a long-term decline in death rates changed direction in 1999 for middle-aged, non-Hispanic white Americans, especially for the segment of that population with only a high school degree or less. The study points to high rates of poisoning and suicide as the leading reasons behind the rising death rate.

For comparison, the study authors looked at six other industrialized countries, including Canada, but did not observe a similar pattern.

In Canada in 2011, the suicide rate for men in their 50s was about 24 per 100,000, also the highest of any age group. Statistics Canada had not released the numbers for more recent years, even though the 2011 statistics were released in January 2014.

Numbers made available to CBC News by the Ontario Chief Coroner's Office show that the numbers of suicides among that demographic group rose in 2012 and again in 2013.

Suicide rates rise during recessions

According to a 2015 study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, "the total suicide rate tends to rise during periods of economic recession and fall during expansions," adding, "The effect has been particularly pronounced for the middle-aged and for men."

That U.S. study, by Katherine Hempstead and Julie Phillips, found that "Relative to other age groups, a larger and increasing proportion of middle-aged suicides have circumstances associated with job, financial, or legal distress."

A 2014 report by Toronto Public Health found the most common stressors in suicides by men aged 45 to 64 were employment and financial, which rank ahead of interpersonal conflict, the most frequent stressor overall in the Toronto suicide cases studied.

Looking at the so-called Great Recession that began in late 2007, Reidenberg says this time was different because in past downturns there wasn't as significant a rise in suicides among just one age group.

He says it wasn't just higher unemployment but a much broader impact on middle-aged men, that also includes the fear of becoming unemployed, losing homes and the fear of losing their homes, losing their pensions and /or their health-care benefits they get through their workplace, and losing a significant share of their savings or investments.

As a sandwich generation, with both children and their own parents to care for, that age group faces additional pressure.

Bilsker wants more research on men's career trajectories and suicide. "Is there something happening to men occupationally in their 50s that is contributing to suicidality, is it contributing to a sense of despair?"

He speculates that there may be an impact from "an occupational world where there's an increasing emphasis on younger workers coming in, with newer ideas, and quickly changing technology." At work, men in their 50s may feel that "they're seen as less useful, as not having knowledge to bring, that there's less valuing of organizational experience or wisdom, etc.," and that this leaves those men feeling somewhat marginalized.

Alcohol use a factor

While experts struggle to understand the reasons for the high suicide rate in their 50s, it's also important to consider why men in general have a suicide rate about four times higher than women. First of all, there's the issue of mental health problems — an issue in the vast majority of suicides — and alcohol and drugs.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, in tests following completed suicides, about a third of the people tested positive for alcohol, about a quarter for anti-depressants and about a fifth for opiates, including heroin and prescription painkillers.

Those substances add fuel to the fire for people already at risk of suicide, Reidenberg says.

Bilsker says they are a wild card in explaining suicide rates, as "some of the effects of hazardous drinking only start to kick in in the 50s."

Men in particular drink more alcohol when they are going through a bad emotional time, Bilsker says, adding that's "a very dangerous way of coping emotionally."

Also, the baby boom generation, at all ages, has had a higher suicide rate than other contemporary generations, for whatever reason, and that too may be part of the story for men in their 50s.

No simple explanation

"There's never one reason for any suicide, there's always multiple reasons," Reidenberg says, echoing the views of other experts.

Both Bilsker and Reidenberg say how men cope with emotional suffering is also a critical part of the explanation. They say the challenge is getting men to reach out to others for interpersonal support, or for professional help like counselling or psychotherapy. "Men are far less likely to have done that in the six months to a year before carrying out a suicide action than women," says Bilsker.

Reidenberg says we need to better understand, "Why is it that some men can make it through something so terrible in their life at one moment and at another moment they can't; what is the difference?"

For some of us, for some reason, when the stress and the despair and the hopelessness build up, our coping skills seem to fall apart and not work the way they did earlier in life, he says, but experts don't know why.

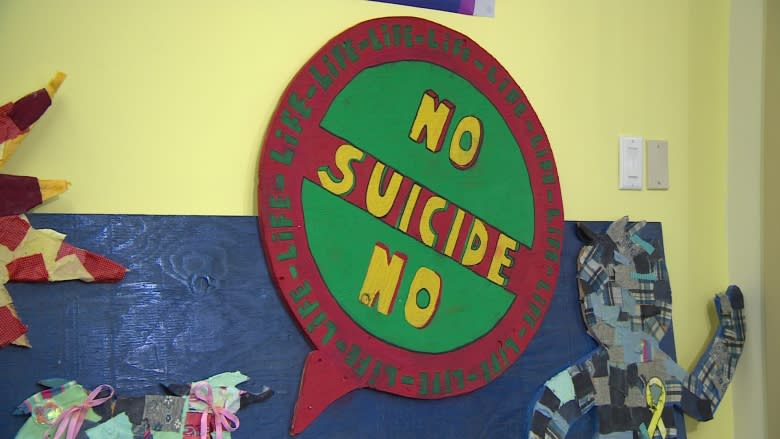

In crisis and in need of support? This Movember Foundation webpage will guide you to sources for immediate and long-term support.