Teachers, families prepare for 1st day of school for Syrian refugee kids

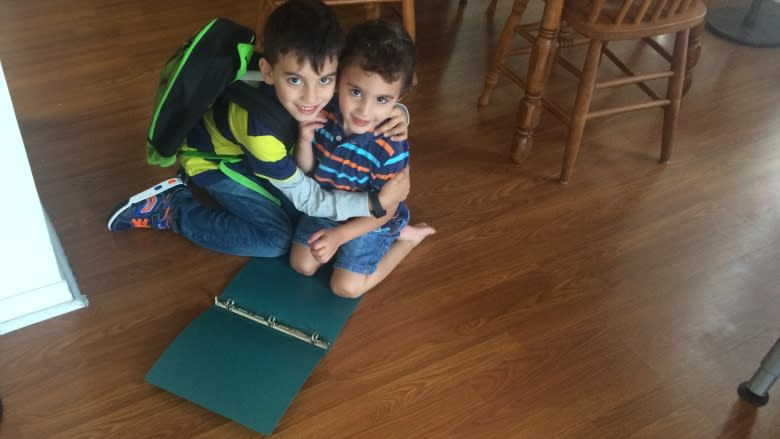

Safi Al Sahen is excited.

The six-year-old refugee from Syria just arrived in Canada this summer, so he doesn't yet know a lot of English. But he does know the colours of the bandanas adorning the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles on his brand-new backpack.

"Ninja!" Safi says as he points to the bag. "Red. Blue"

"Purple!" his little brother Rafi, almost three, exclaims.

"Purple, orange, green," Safi continues, ignoring the interruption.

Safi proudly puts on the backpack, along with his new running shoes, and won't take it off as he sits in his family's Mississauga, Ont., apartment. He'll put his gear to use on Tuesday, when he starts Grade 1 for his first day of school in Canada.

"He's happy to go to school," said his mother, Amani Al-Habyan, using the English she's spent the last two months learning. "Safi likes to learn and play and practise many exercises and activities."

But like thousands of children whose families have fled Syria, Safi faces a steep learning curve as he plunges into a foreign school system while trying to learn English — a daunting task for any newcomer, but with the added burden of having lived through conflict.

"When you have war and trauma in these regions, what's going to follow suit is mental health problems" said Mazen El-Baba, a graduate student in neuroscience at Western University, who is studying the emotional and developmental well-being of Syrian refugee children.

"[The problems] vary from one person to another."

Amid the constant bombing and fighting before they left Syria more than three years ago, Safi started stuttering, Al-Habyan said. It remains her biggest worry as her son starts school.

"I will go and speak to his teacher and explain," she said.

Talking to parents and establishing a relationship with them is a key way to ensure students new to Canada feel comfortable and safe at school, said Steve Webb, the principal at Chris Hadfield Public School in Mississauga, where Safi will go.

"The kids are nervous when they come, the parents are a little worried about, you know, leaving their children here and going off," Webb said. "We want them to know that they are welcome, and their students are welcome and we'll look after them."

Although fewer than 10 refugee children from Syria came to the school last year, it has extensive experience welcoming newcomers to Canada, Webb said, noting that its more than 600 students speak 38 different languages, including Arabic.

The school has three English as a Second Language teachers, he said, and classroom teachers match new students with another child who speaks the same language to be a "friend" for the first week.

"They look after them at recess, making sure they know where the washrooms are, making sure that they know it's time to eat ... where they can play," Webb said. "They're little things, but they're important."

Schools in Mississauga and other parts of the region received more than 560 Syrian students between January and June, according to the Peel District School Board, with another 40 registered to start school for the first time on Tuesday.

The principal of a nearby school that took in more than 70 Syrian refugee students last term said one of the most important things teachers can do is to "encourage them to leverage and use their first language to help them learn English."

"One of the problems I think that many immigrant or newcomer students felt, you know, in education in the past, was that ... they were silenced right away," said Robert Di Prospero, principal of Thornwood Public School.

People tended to assume that newcomers were quiet because of the "overwhelming feeling of coming into a new country," he said, when the problem was really that "they had no voice in the classroom."

Having kids speak and write different languages, as well as using computer translation apps, has been enriching for all students in the classroom — not just the newcomers, he said.

"They learn from us [and] we learn from them," Di Prospero said. "[We're] not looking at these students as a deficit of what they don't bring."

"[We're] sort of flipping that around and saying what do they bring?"

A significant factor in the school's ability to welcome refugee students is the availability of English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers, he said, noting that he has four for the upcoming year.

Brian Woodland, spokesperson for the Peel District School Board, said funding for ESL support comes from the Ontario government and is based on the number of students being served.

Highly multicultural schools are also able to involve students in bridging the language gap with Syrian refugee children, giving them leadership opportunities, both Di Prospero and Webb said.

Although that's valuable, teachers shouldn't feel that they have to pick someone who speaks the same language when they're choosing a "buddy" to partner with the new child in the classroom, said Safiya Shere, an ESL teacher at Thornwood Public School.

"You can still be friends with people even if they don't speak the same language as you," she said. "I think that's something that I really picked up on this year."

"The common language that you'll see kids share, especially out there in the playground, you know, they play soccer together or, they just have a way of communicating," Shere said. "Although it is definitely useful to have somebody who speaks the same language as you in the classroom ... you can't force those friendships."

One of the most important ways to welcome refugee children to school is also one of the easiest, said Anne Marie Chudleigh, one of the private sponsors for Safi's family, as well as a teacher at the University of Toronto's Ontario Institute For Studies in Education (OISE).

"Smile," she said. "Say, 'Hi.'"

"Welcome them with your body language. It's really the simplest thing."

Listen to Safi and his mother Amani on CBC Radio's The World This Weekend on Sunday at 6 p.m. (7 p.m. AT, 7:30 p.m. NT).