Tell us: How should governments tackle poverty in Canada?

Poverty in Canada doesn’t just look like low wages, expensive rent and an absence of personal savings.

It looks like avoiding the dentist, bi-weekly visits to a payday loan store, foregoing warm clothes for winter and living far away from work and school.

These are some of the findings of a new study from the Angus Reid Institute. The study measures the state of poverty in the country by looking at personal experiences, rather than income. The results are striking.

One-in-five Canadian adults who participated in the study said an inability to afford dental care has been a chronic problem throughout their lives.

One-in-six routinely can’t afford new clothes or good-quality groceries. One-in-seven have lived for years in homes that are too small, too far from work and school, or both.

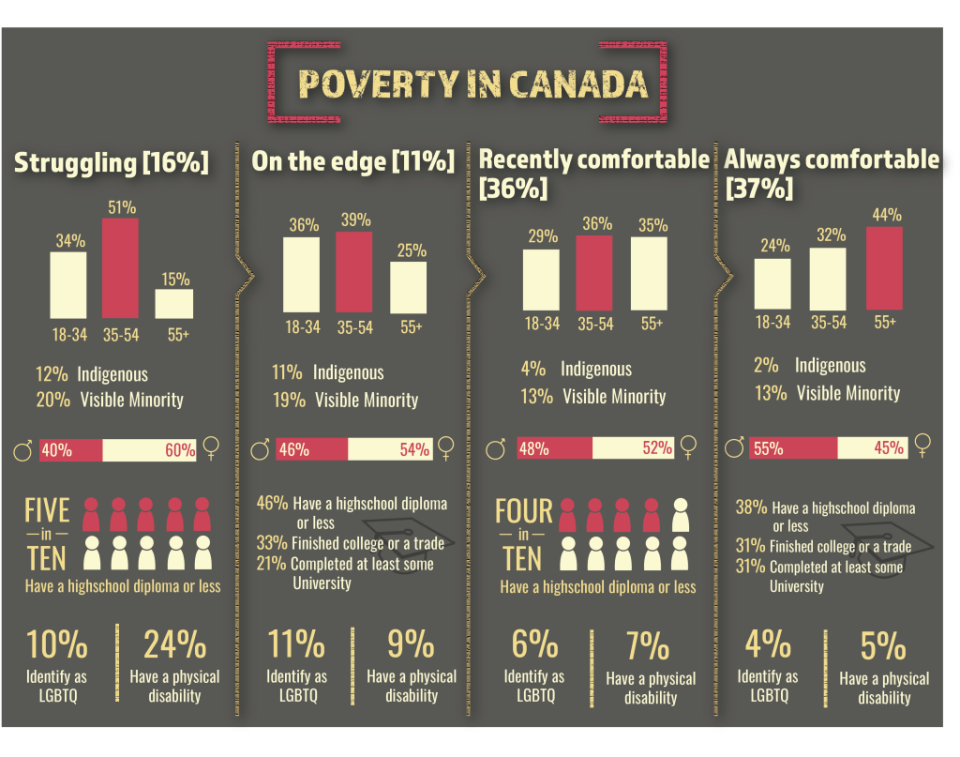

Researchers used these lived experiences with poverty — and others, including using a food bank and relying on cheap “filler” food — to place Canadians in four groups: the struggling, those on the edge of struggling, the recently comfortable and the always comfortable.

“Segmenting Canadians by their personal histories with financial struggle leads to groups that don’t fit neatly into low, middle, or high-income categories,” the study says.

In this case, to struggle means to face financial challenges that negatively impact quality of life.

The study found that more than a quarter — 27 per cent — of Canada’s population is either struggling or on the edge, or is experiencing serious financial hardship. Nearly one-in-three Canadians feel “very stressed” about money on a regular basis, the data shows.

The study also asked respondents about their perceptions of poverty, and found more than half the population believes poverty is increasing where they live.

Three out of 10 people are pessimistic about their own financial situations, and 43 per cent of Canadians believe their children’s generation will be worse off than they are.

The study reveals women are more likely than men to struggle, people who are 55 and up are more likely to report feeling comfortable, and Indigenous people, visible minorities, people who identify as LGBTQ and those with physical disabilities are all more likely to be struggling, or close to it, than comfortable.

Experiences with poverty weren’t equal from one part of the country to another, either.

The highest number of respondents— 50 per cent — who said they were dissatisfied with their current financial situation were in Atlantic Canada. Saskatchewan had the lowest number of dissatisfied respondents, at 30 per cent.

But it was people in Manitoba, not Atlantic Canada, who were most pessimistic about their personal financial situations over the next few years. The most optimistic respondents were in Quebec.

The study didn’t make any recommendations for addressing poverty in Canada. But a second chapter expected to come out later this summer, will focus on Canadians’ attitudes, their empathy for people who are struggling and their support for poverty-busting policy proposals.

The federal government released a similar report summarizing ideas and feedback about poverty reduction in February. It gathered the information in conversations with Canadians across the country over a year.

Employment and Social Development Canada said the government would use the report to develop Canada’s first-ever national poverty reduction strategy.

“It is by working together that we can make a difference in reducing poverty in our communities,” said Jean-Yves Duclos, Minister of Families, Children and Social Development. “And help all Canadians have a real and fair chance to succeed.”

How do you think governments should deal with poverty in Canada? Share your ideas in the comments section below.