Today it’s a jail. But it was originally the last segregated school built in Fort Worth

The last racially segregated school built by a defiant Fort Worth ISD was the Ninth Ward Colored School in 1958. This was four years after the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, decision that declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

It took Fort Worth until the 1960s to be dragged into compliance.

The Ninth Ward School was not always designated for Black children, and the name itself was applied to several campuses over the years before its final incarnation at 1815 Cold Springs Road. The city let the bid for a Ninth Ward School in 1892, to be located on McCart. The schoolhouse was completed in 1894, consisting of six rooms. All five teachers were white as were all the students, who numbered 227 by 1900. By 1912 the building was in serious need of repairs, leading some mothers of students to protest to the school board.

It eventually got a more appealing name, Travis School, in honor of Alamo martyr Col. William Barrett Travis. The school was relocated repeatedly, first to East Belknap (backing up to Weatherford), then to Grant Avenue (near Pioneers Rest Cemetery) before landing on Cold Springs Road. In the early 1920s, the white student body was combined with that of the First Ward/Huffman School and the old building was turned into a school to serve the rapidly growing African-American population living in the area.

That was the beginning of a long, steady decline of the building.

In 1925, an inspection found the building “in a bad state of repair,” so bad that in 1927 the city constructed a new building for the Ninth Ward on Samuels Avenue. By 1930, 93 children were enrolled in what the Star-Telegram characterized as “the worst building” of all Fort Worth schools. Among other problems, it was subject to flooding whenever the Trinity River overflowed.

Superintendent M.H. Moore agreed that something had to be done, calling the two-room building a “shack” and adding that it was “unfit for human habitation.” He said the students would be moving into a new building soon.

The new school, still one-room and still on Cold Springs Road, was constructed for $4,000. It looked better but was still in the floodplain and of cheap, wood-frame construction. It served children living east of Main, north of Belknap, and south of the Trinity River, an area that did not attract residential development until 1944 when Greenway Place was developed between Greenway Park and the city dump. Even then, it was zoned for heavy industrial use.

In 1931, the little schoolhouse between railroad tracks, the city dump, and the Trinity River enrolled 31 children, all of them Black. In the years that followed, as the number of students grew, the campus had to be expanded. In 1937, a two-room outbuilding was moved from the campus of nearby Charles E. Nash Elementary (Samuels Avenue) to the site.

The school’s problems, aside from its out-of-sight, out-of-mind location, began with water. It was washed out in the big flood of 1949. Most of the city did not notice because attention focused on the Seventh Street corridor, but the school year could not be canceled. Classes were moved to St. James Baptist Church.

Another problem was the proximity of the city’s only public dumping ground. In 1951, the municipal sanitary engineer chastised citizens for dumping their garbage in their neighborhoods and encouraged them to use the dump. This public announcement came just a couple of weeks before school opened, so part of the view students got was of people dumping their garbage next door.

The buildings also had no security. In 1955 burglars broke into the main building and took money and food.

A 1952 bond election raised funding to build several much-needed schools, including a new Ninth Ward School, at the bottom of the list of priorities. The money for it was enough to purchase a new site and build a modern building. Three years later, school authorities were still seeking an appropriate site, which meant finding an affordable site in a welcoming neighborhood.

Finally, in 1956, the present site was purchased from the Rock Island Railroad, which was in desperate financial straits. While waiting for what the school board called a “permanent building,” Ninth Ward students continued to go to school in wood-frame shacks moved from other sites.

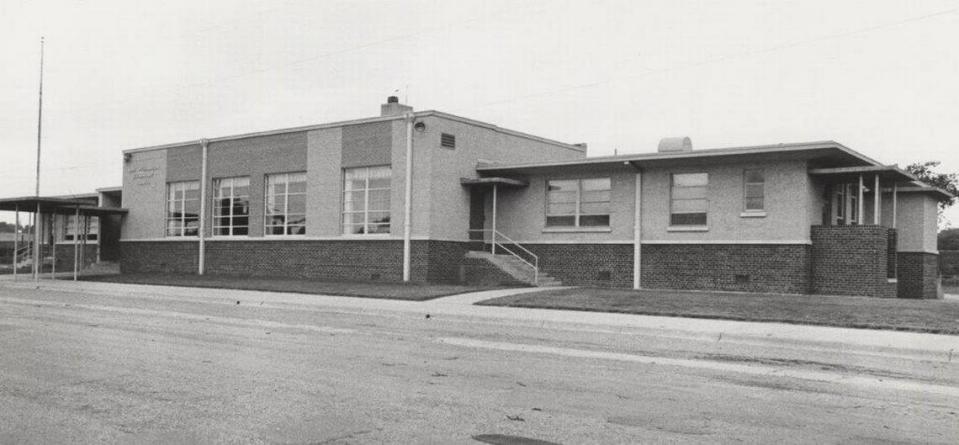

Plans for the new building were revealed in the summer of 1956: a two-story, brick building with 12 spacious classrooms, each with large windows to provide plenty of fresh air and sunlight, no playground equipment, and no air conditioning, which no Fort Worth school had at this time. The board allocated $287,000 for the project, which not even the lowest bidder could meet, meaning the contract had to be rebid. The building was supposed to open in time for the 1957-58 school year.

While cost and opening date might be subject to change, there was never any question that this was going to be a school for Black children, no matter what the Supreme Court said.

The school had a dedication ceremony and open house on May 4, 1958. All the speakers were white, but the general public was invited, which presumably brought out residents of the Black neighborhood the school would serve. The old buildings on the site were removed to the “rehabilitation camp for winos” on Lake Worth. The new building was a nice improvement over the old campus, but it was still in the worst location of any Fort Worth school — next to the city dump with railroad tracks on three sides.

Still, for the more than 200 students who attended, it was an improvement over the old buildings. As one school official explained in 1964, the Ninth Ward school was only in a “blighted” area because, “We have to put the schools where the children are. The fault is not with the school system but with the social order.” That was the same year the school got a more appealing name, Ruby Williamson Elementary, named for the African-American woman who had been principal from 1935 to 1961.

Under growing public pressure, the FWISD closed the school in 1968. Its students were bused to other newly integrated elementary schools. In 1985, the county announced plans to convert the empty building into a minimum-security lockup. The move was necessary, officials said, because the county had outgrown its existing jail. The Cold Springs site was chosen because it was a large, occupant-ready building close to downtown so that prisoners could be easily transported back and forth to the courts.

The transformation from school to jail was completed by 1988, making this the fourth county lockup. At its peak in the next seven years, more than 1,000 prisoners were incarcerated there. Additional “barracks” had to be built on the grounds to house that number of prisoners. In 1992, improvements were made to turn the site into a medium-security jail. In 1995, the county closed the Cold Springs jail, transferring the last 200 prisoners to other facilities. At the time it had accommodations for 384 inmates.

Four years later, the county needed more jail space and announced plans to reopen the Cold Springs site with one big difference; they planned to lease it to a private company. It would operate as a minimum- and medium-security facility, even taking in federal prisoners on a short-term basis. Reopening it met two pressing needs: more inmate space and more revenue for the county.

Greenway residents, however, were not eager to have a jail in their neighborhood again. It would not add value to their property or provide a service for residents, and it might prove dangerous if prisoners escaped.

The Cold Springs jail site is still open today.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.