Toronto's first black mailman honoured 135 years after he started on the job

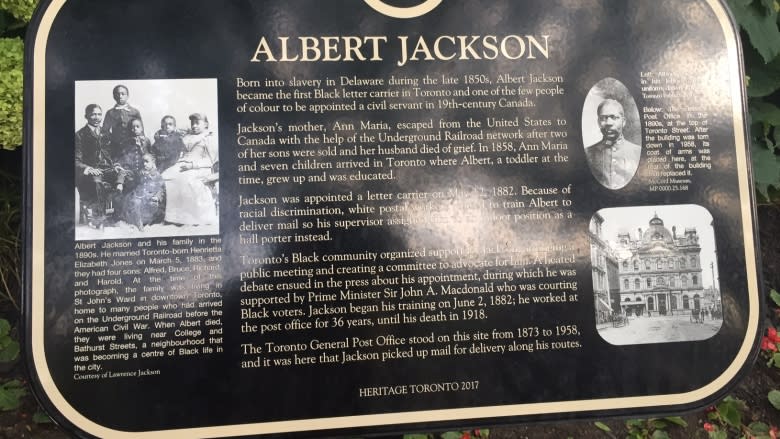

It's been 135 years since Albert Jackson had his first day of work as Toronto's first black letter carrier, a job of which the then-25-year-old had long dreamed.

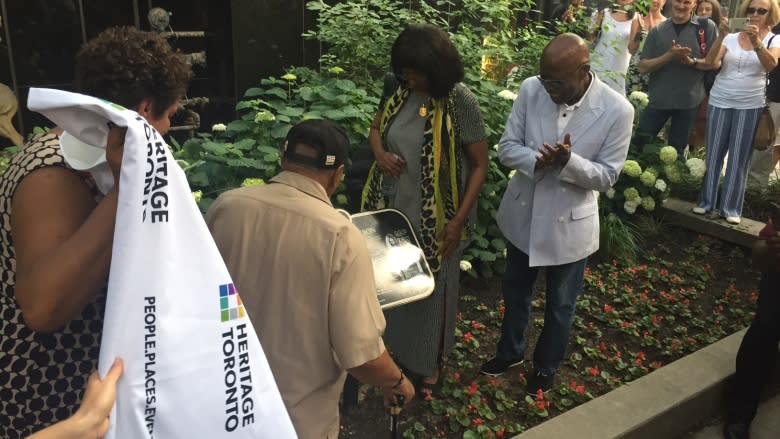

Heritage Toronto honoured that achievement Friday by unveiling a commemorative plaque, an idea proposed two years ago and since pushed for by Jackson's family and supporters. It stands at the old Toronto General Post Office, located near Victoria and Lombard streets, where Jackson used to pick up mail to deliver on his routes.

He worked his first day on May 12, 1882.

"I can't even tell you the emotions that are running through me," said Jackson's great-granddaughter, Shawne Jackson-Troiano, who spoke with Metro Morning before attending Friday's ceremony. "It makes me very emotional."

Jackson's success came after a difficult and discriminatory beginning. That first day on the job, his white colleagues refused to train him.

"The black community banded together, there were protests, the newspaper actually picked up the story and kept running it, and it was brought to the attention of Sir John A. Macdonald," Jackson-Troiano said. "That happened because it was an election year and John A. Macdonald needed the black vote."

A story meant to be told

Jackson was born in the state of Delaware during the 1850s. His two eldest brothers were sold as slaves, which is said to have triggered the death of Jackson's father.

His mother, Ann Maria, escaped from the United States to Canada with seven children on the underground railroad. Albert was the youngest and just a toddler at the time.

They ended up at the home of Lucie and Thornton Blackburn, where they stayed until they made enough money to get on their feet, according to Jackson-Troiano.

"I couldn't even imagine what my great-great-grandmother went through with seven children, one being a baby, coming here through the underground railroad not knowing from one day to the next where she would end up. She just knew she wanted freedom for her family," Jackson-Troiano said.

Albert worked at the post office for 36 years until his death in 1918. And his living relatives knew little of his achievements until recent years.

In 1985, an archeological dig at the Blackburn home turned up several artifacts, including birth and marriage certificates linked to the Jackson family, according to Jay Jackson, Albert's great-grandson. Coincidentally, Jay Jackson worked at the Ministry of Citizenship and Culture at that time, and he was the one to give the dig the approval to move forward.

"We just couldn't get over the coincidences that kept happening," Jackson said. "A lot of it we knew orally. When you support it with documentation it's more valid."

At the beginning of her speech Friday, Jackson-Troiano added that this was "a story that was supposed to be told."

Jackson-Troiano helped pull the cover off the plaque Friday, overcome with emotion when it was finally unveiled.

"It's beautiful. I wish my dad could see it because my dad looked like Albert," she said. "It's been a long walk, but worth every single second."

Albert Jackson's only living grandson, Lawrence, also helped to reveal the plaque.

"It was hard for me to speak because I was almost choking up," he said, after telling the crowd how perseverance pays off. "Don't give up hope, there are ways."

The plaque is just one of several dedications Jackson has received across the city and beyond.

In March 2013, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers presented a commemorative poster to Jackson's family. In July of that same year, a laneway behind his former home in Harbord Village was named Albert Jackson Lane. A play and a book have also been created in his name.

They're adaptations of the story that gives Jackson-Troiano and her family immense pride.

"I think often about the cushy life I lead and how they just paved the way for all of my family so that we could have what we have today."