Trump wants schools reopened. He's getting rare support from virus experts

Donald Trump's call to reopen schools is winning rare qualified support from a group that's included some of the U.S. president's harshest critics: virus experts.

Public health professionals who have castigated the president's pandemic handling agree with him that students should be in classrooms this fall.

Several interviewed by CBC News said the evidence favours a safe return to school, though they added caveats about how to do it and about the need to plan it carefully.

They offered that advice while stressing that the president otherwise has little credibility when speaking about COVID-19, which he has repeatedly downplayed, made untrue claims about and promoted unproven treatments for.

On this, they say, he's got a point.

The debate is of increasingly urgent relevance to parents across the continent, as policy-makers in U.S. states and Canadian provinces weigh different approaches for reopening classrooms in several weeks.

"I'm very, very, very, very, very non-pro-Trump. But this is an issue — it should not be a political thing. It should be based on the science," said Dr. Michael Silverman, chief of infectious diseases at the Health Sciences Centre in London, Ont.

"And the science says the kids should be going back to school," said Silverman, who has completed a paper on the topic, now undergoing peer review.

"There is a consensus among the vast majority of us [in this field] that the schools need to open. And they need to open soon."

The message was similar from two other epidemiologists interviewed by CBC News, as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics.

"In general, I still wouldn't listen to the president on anything having to do with the coronavirus," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

"It just happens to be a coincidence that he might have said something that's backed by epidemiological data in this case."

Ashleigh Tuite, an epidemiologist at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto, cautioned that areas with serious outbreaks should delay a return, but she said: "Schools should reopen in the fall. I think it's a priority."

Trump's election message

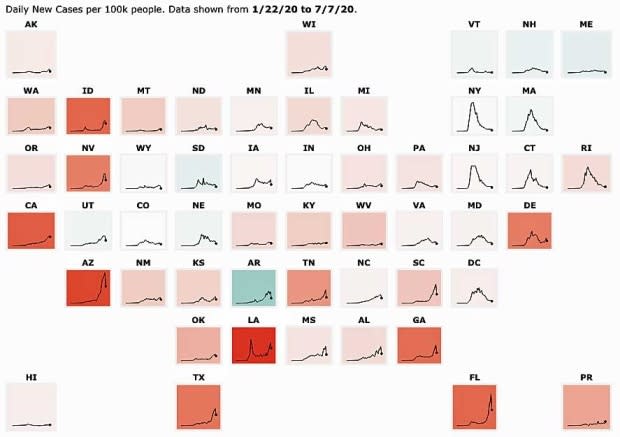

Even as case totals soar across the southern U.S., Trump seems to be keen to campaign for this November's election on the idea that life is returning to normal.

He has put schools at the centre of that narrative — this week he tweeted repeatedly and held different White House events about reopening.

"The moms want it. The dads want it. The kids want it. It's time to do it," Trump said at a White House event on the topic.

"We're very much going to put pressure on governors — and everybody else — to open schools."

In a tweet that puzzled public health experts, Trump has even pressured the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to be more gung-ho, and he blasted the agency.

The CDC's recommendations currently include a nine-page checklist for schools on everything from cleaning to distancing practices.

It also offers guidelines for different regional scenarios, saying places with some virus spread should space desks two metres apart and cancel field trips, while places with more severe spread may want to consider shuttering schools again.

The CDC suggests mask-wearing when feasible and is releasing additional guidelines in a few days.

U.S. federal immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci said this week that different parts of the country might use different approaches based on their current caseloads.

But Fauci's broad message was that the overall damage to children being outside the classroom is outweighing the benefits: "We should try as best as possible to get the children back to school and the schools open."

How to reduce risks

Adalja mentioned four things schools can do to reduce the risks of reopening schools:

Have a plan for what to do if cases occur.

Allow at-risk school employees with pre-existing medical conditions to work in isolation.

Create safer spaces: Open windows and hold classes outdoors when possible; separate desks to the greatest extent possible; and try not to shuffle children between classes. (Tuite suggested using churches or universities to add extra class space.)

Make it voluntary: If a family wants children to study at home, let them.

There is some disagreement among experts about what to do in the event of a regional spike in cases — a current problem in southern U.S. states.

Adalja said he favours a more aggressive reopening.

He said he'd be very hesitant to close schools again, even in harder-hit areas. "I was never a major proponent of closing schools because I didn't think there was strong data to support it."

The only reason authorities closed schools this spring, Adalja said, was fear that the virus would act like influenza — dangerous to children and easily spread by them.

But COVID-19 is the opposite, he said.

Children's 'puzzling' response to COVID-19

There's no complete consensus yet on children's low risk of spreading the coronavirus. But Dr. Howard Njoo, Canada's deputy chief public health officer, said Wednesday that officials are weighing the evidence.

"From the science, what we know is that certainly young people, children, are less likely to have more severe consequences if they do get infected with the virus," he said.

"It also appears that in terms of transmission, young children — at least in some of the studies I've seen — do not appear to be as efficient or effective in terms of transmitting the virus to others."

Njoo said that aspect was "at the heart of the debate." In terms of managing risk, "it is a bit of a social experiment," he said.

Adalja said children rarely spread, and are rarely seriously harmed by, COVID-19, based on international evidence from daycares used by the children of essential workers in the U.S.; studies in Taiwan, Finland, Denmark and elsewhere; and states that reopened schools.

Silverman said it's equally true of Canadian provinces, some of which reopened classrooms in the spring, with flexible rules and regional exceptions.

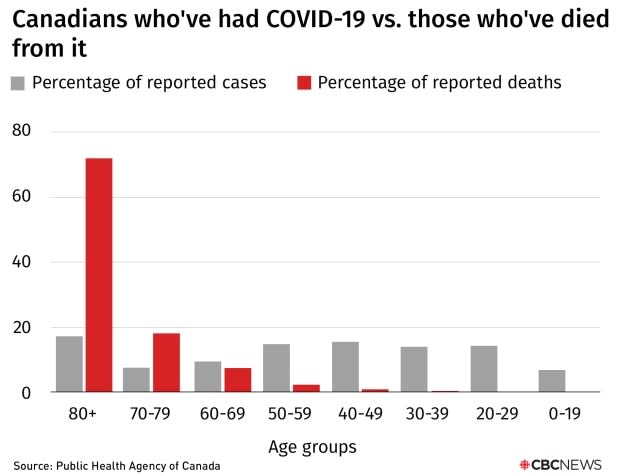

He said Canada has had more than 8,000 adult deaths and no child deaths from COVID-19. There is ample evidence that children don't easily spread the virus, he said.

"We have to educate the public.... Understandably the public is very frightened [about reopening schools]," Silverman said.

"[But] the rationale for continuing to keep kids out of school is misguided. More than that, it's harmful.... Millions of children are being kept out of school to prevent something extremely rare. We're doing harm to millions of children."

Researchers at Brown University in Providence, R.I., attempted to estimate the academic impact of closing U.S. schools this past spring. They published a working paper that said students would lose between 32 and 73 per cent of the likely learning gains in math and reading they would normally have achieved in the 2019-20 school year.

The hardest impact would be on poorer and at-risk students, they said.

Different opinions about what to do in places with spikes

As for places like the U.S. South, with a surge in cases, Silverman said he might take a middle-of-the-road approach. For example, he said, elementary schools might stay mostly open, while high schools could mostly shift back to online learning.

Tuite said she would take a slower approach in areas like the southern U.S.

"I would suggest deferring [reopening]," she said.

Tuite provided a rule of thumb to help authorities decide whether to shut down: Are officials able to contact trace the individuals spreading an outbreak?

She said that's more useful than setting a number of cases as your benchmark for opening or closing, because raw numbers can be deceiving.

For instance, 10 new cases found randomly in a community is greater cause for alarm than 10 cases traced to one single event, Tuite said.

"[But if tracing is] not happening, I don't think you could safely reopen schools," she said.

Teachers' concerns

Teachers' unions are expressing concern about safety.

The largest U.S. teachers' union said the country hasn't properly funded efforts to supply protective gear and modify classrooms.

Other education unions in the U.S. also aren't happy.

In Canada, Ontario's largest teachers' federation sent the provincial government a 37-page document with requests, including the need to respect collective agreement rules on workload and safety issues.

Ontario high school and Catholic teachers' groups have sent similar requests and said the provincial government has not consulted meaningfully.

Different provinces are planning different approaches this fall.

Quebec, Alberta and Saskatchewan say they're preparing for a return to near-normal conditions for most age groups. B.C. and New Brunswick envision a hybrid, partial-normal return. Nova Scotia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Ontario say they're preparing for three scenarios. Ontario and P.E.I. have asked school boards to map out those different scenarios.

Tuite said policy-makers are right to prepare for different scenarios — including for the need to shut down again.

"It's not going to be a typical school year," Tuite said. "You're probably going to have interruptions."