Unable to find work, many Syrian refugees reluctantly turn to social assistance

Syrian refugee Ragheb Alturkmani arrived in Canada on a cloudy day on Jan. 27, 2016, unable to say a single word in English, but brimming with happiness he couldn't express.

After he and his wife moved with their young daughter and two teenage sons into the Halifax apartment that would become their home, he decided he wanted to give back to the community that had welcomed his family.

"I found myself going down, cleaning the street," Alturkmani says through an interpreter. "Here I thought I was doing good, helping people by cleaning the entrance of the building."

Alturkmani smiles as he recalls how he swept up what he thought was dirt: It turned out to be salt, put down to de-ice the sidewalk.

"We have so many people with us who have the desire to work and to be productive," he says.

Seeking work, finding frustration

But Alturkmani, a former school bus driver, is still out of work — and he's not the only one.

For their first year after landing in Canada, refugees are supported by either the federal government or private groups. But that support has ended for most Syrian refugees, and many of those unable to find jobs have turned to provincial social assistance.

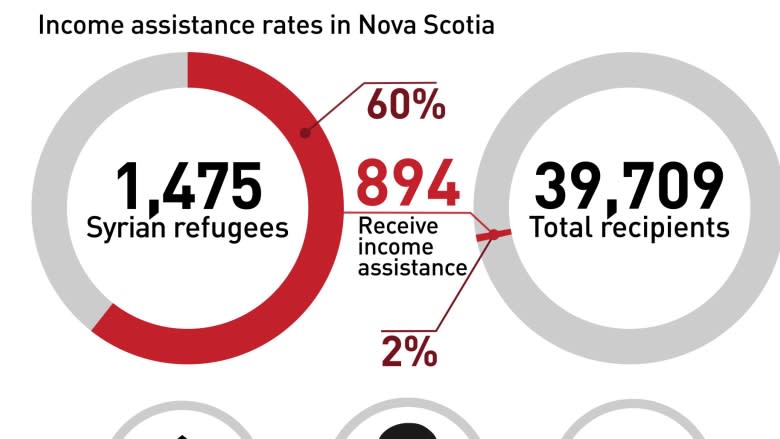

Just shy of 1,500 Syrian refugees landed in Nova Scotia between November 2015 and July this year. Of those, more than half — 894 adults and children — were on income assistance as of late September, according to the province's Department of Community Services.

Syrian refugees represent about two per cent of the total number of Nova Scotians receiving such benefits. Income assistance in Nova Scotia includes $620 a month for shelter for a family of three or more, and an additional $275 per adult and $133 per child each month for personal expenses. Families may also qualify for the Canada child benefit program.

The problem for many refugees who haven't found work is a lack of English-language skills. Another is having Syrian work or educational credentials that aren't recognized in Canada.

The latter weighs heavily on Easa Al-Hariri, who worked as a dentist in Daraa, a city in southwestern Syria, and had a second job in health-systems management with the country's Ministry of Health. He, his wife and their four children now live in Dartmouth.

"I am very depressed," he said in an interview at his family's small townhouse. "For me, it's not just a matter of finding a job or not, to make a living. It's a matter of success or failure. This is what I think about.

"Because already we receive social assistance, actually this is for me very embarrassing," he said. "I used to help people, not people help me."

Al-Hariri is studying full time for his upcoming foreign qualification exams in Canadian dentistry. He is also studying to bring his conversational English to the required academic standard.

He feels he will soon be ready to combine studying with a part-time job. But he can't bring himself to take full-time work in a field outside dentistry, fearing that he may never return to the profession he loves.

He's willing to work under the supervision of another dentist, and suggests low-cost exam preparation courses would help — the type he has seen in other provinces.

As much as he is grateful to the Dartmouth community group that sponsored his family, Al-Hariri feels he is on a solo mission when it comes to getting his credentials recognized. Yet he is determined to succeed in his new home.

"I feel I belong to this place and the people who helped me to adapt here, helped my kids. They became part of my family here," he said.

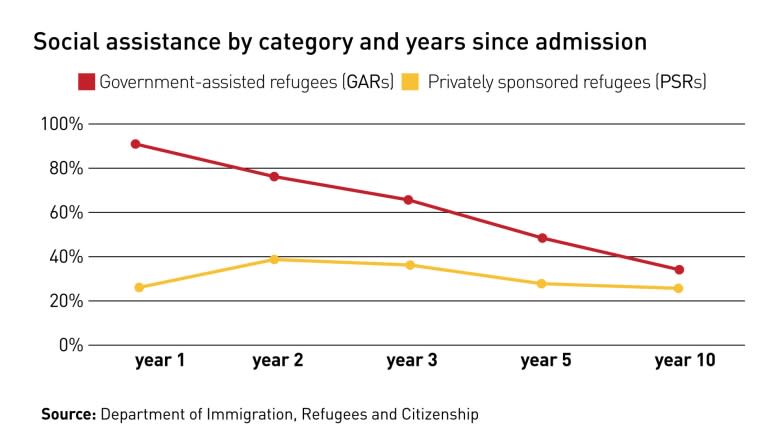

Difficulty finding work in the first few years is not unusual for refugees, regardless of their country of origin.

Statistics Canada data shows that, historically, about 93 per cent of new government-assisted refugees received at least one month of social assistance. That number drops over time to roughly 34 per cent in 10 years, and continues to drop with more time in Canada.

In late 2016, the federal government did a rapid impact evaluation of the Syrian refugee resettlement. The survey showed about 10 per cent of government-assisted adult refugees across Canada had found work, while around 53 per cent of privately sponsored adult refugees had jobs.

In Nova Scotia, the numbers appear encouraging when compared to federal statistics. Forty per cent of the newcomers are not on social assistance, according to the Department of Community Services, suggesting they or one of their family members have found work.

At the Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia, one of the major agencies working with Syrian newcomers, executive director Gerry Mills points out that settlement workers always knew the refugee cohort would need some short-term support to get established.

"The Syrian refugees, all refugees, are never brought into the country to be able to respond to skills shortages. This is a humanitarian response," she said.

"A short amount of money to invest to be able to get them to where they need to be, to get them to be contributing members of the economy, is worth it."

ISANS has had success in helping about 150 Syrian-Nova Scotians find work, Mills said, sometimes through starting their own businesses or by using bridging programs that partner with industry.

But the influx of Syrian refugees highlighted systemic issues that affect all low-income families, such as the lack of affordable housing, she said.

"For instance, some of the sponsorship groups suddenly were forced to find affordable housing for their families that were going to come. They were thinking, 'People can't live on this,'" Mills said. "Well, your neighbour does."

Mills said the number of refugees on social assistance must be placed in context. It is much lower than the total number of Nova Scotians, about 40,000, who receive the benefits.

"We're not talking a lot of people," she said. "The norm is really small. We don't take in that many refugees in Nova Scotia."

Ragheb Alturkmani and his wife, Abir Albasha, have mixed feelings about income assistance. They both attend English-language lessons full time while caring for their children.

Their sons and daughter are now nearly fluent, and after a year of study, Alturkmani has raised his English to Level 3 of 10. But neither he nor his wife has the fluency required to find work yet, leaving them on income assistance for now.

"It's miserable; I don't know what to do. Because this is the only alternative we have," said Alturkmani. "We, all of us who came here to Canada, would love to work. None of them would like to live by the government support."

Alturkmani feels that if he could get work where he could interact with English speakers, it would help him pick up more words on the job. For now, he continues with language studies.

"If we have the opportunity to work, we will be able to give a different picture to the one they are seeing now," he said.