Uncovering the mysteries at the bottom of the Labrador Sea

Prior to the summer of 2017, the one thing researchers knew about the depths of the Labrador Sea was that they didn't know much.

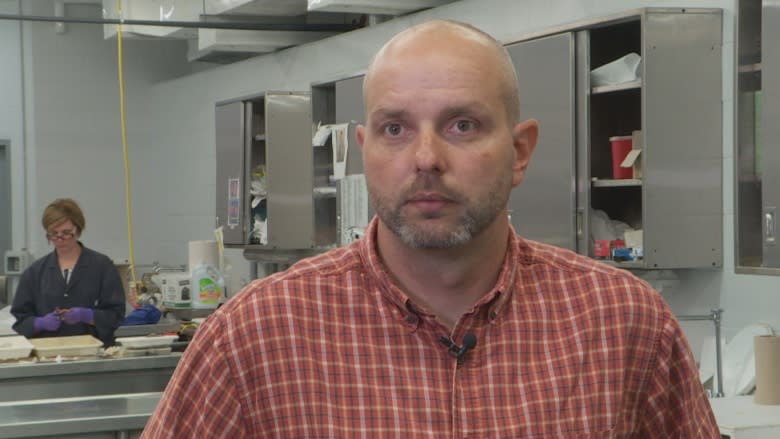

"We really knew virtually nothing of what was living in the bottom," said David Cote, a research scientist with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO).

But Cote and a team of experts are beginning to put that ignorance into the past tense, as they gear up for a second summer stint on the Labrador Sea using a mix of Victorian-era methods and innovative technologies to discover the organisms that thrive from 500 to 3,000 metres down.

There's good reason the area has remained virtually uncharted. Even the sea's surface presents challenging conditions to the scientists, as they try to contend with sea ice and short summer windows to work in. Then there's the thirteen kilometres of line to unravel to conduct tests — it takes five kilometres of line just to get the first baited hook to its destination.

"When we're trying to drop gear to the bottom, it's not taking minutes to get to the bottom, we're talking hours. And the same thing to pull it up," Cote said.

Despite the challenges in the first year of a three-year project, the scientists made some big discoveries in their early days of exploration that has them excited to put on their parkas — the surface of the Labrador Sea is actually colder than its depths, thanks to Arctic currents — and return to their field work in August.

Sponges and corals and fish, oh my

"We actually saw quite a few fish and life down there," said Cote.

From rabbit fish — so named for their rather terrifying long teeth — to sponges and deep water corals, there's no shortage of organisms the team catalogued in the depths. The latter are classified as a "habitat forming species," which help transform the mostly flat ocean floor into an ecosystem friendlier for other species to settle.

Besides interesting invertebrates, the 2017 team was particularly excited to document mature specimens of blue hake.

The big-eyed fish is common throughout the world at depths of 1,000 to 2,000 metres, but only immature species have been captured before, leaving the question of where it spawns a mystery. Snagging mature blue hake suggests that spawning ground could be somewhere in the Labrador Sea.

"As a scientist it's always exciting to have a discovery like that, and we think it's a sign of good things to come," said Cote.

"That's a pretty important finding, but really we're in the early days in this type of research, and we expect over the next couple of years for a lot of interesting things to come out."

Fishing for DNA

Some of the ways the scientists are sampling the ocean floor showcase cutting-edge research methods. While dropping baited hooks down as far as line will allow has been a scientific standard since the Challenger Expedition pioneered oceanography in the 1870s, Cote's team are mixing that up.

Beyond remote operated vehicles and deep water cameras, the scientists are using as well as an emerging technique termed 'environmental DNA.'

"Environmental DNA runs on the premise that all animals are shedding little bits of cells and genetic material into the water column and sediment," said Cote.

To capture that, the team scooped up water and sediment samples from selected spots, and have now begun running the samples back in the laboratory, matching them up in a DNA database to discover what's been swimming in the area.

"So we can actually get a picture of what animals live in that water, without seeing the animals. Which is really important," he said, adding this has been used in other ocean experiments with success.

"The idea behind all these techniques is they complement one another. Each technique has an advantage which may cover off the disadvantages of the other ones.

Race against development

The fieldwork set for August 2018 and 2019 will greatly add upon the team's first forays into the deep northern waters. Cote's team is expanding from three scientists aboard a commercial fishing vessel last year, to a team of 16 this year who will work around the clock aboard the coast guard ship Amundsen, which is well-equipped to handle scientific explorations.

But as the team works to turn mysteries into facts, one thing is already certain.

"We know that as technologies increase and the demand for resources increase, that industries are going to move into deeper and deeper water," he said.

"So we really need to understand what these communities are like before we move in so we can predict these impacts, and we can also potentially manage these impacts."

Establishing a baseline of the marine environment will prove critical, said Cote, as this swath of the unmapped ocean holds sensitive ecosystems, with fragile fish that grow slowly and take a long time to reproduce.

His team has so far concentrated their efforts on 11 sites Cote calls mere "pinholes" in the 100,000 km/sq area. They hope to enlarge those pinholes over the next two summers, tailoring future strategies to their findings. By 2019 he hopes researchers will have a specialized sled built they can drag along the ocean floor, capturing footage.

Cote tempers his excitement over the future with the daunting nature of the depths. Eighty-five per cent of the world's ocean areas have depths greater than 2,000 metres, and an oft-recited trope in oceanography is that the moon has so far been better mapped and understood.

"It's just such a huge hole in our knowledge," said Cote.

"At least we can see the moon."

Read more articles from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador