Unit Photographers Get One Chance to Define an Entire Show — Here’s How They Do It

There’s a first-look photo from “Presumed Innocent” that’s so evocative you’d assume it was planned. In the image from the Apple TV+ series, which premieres June 12, Jake Gyllenhaal stands in a courtroom looking distraught. His hands are clasped in front of his rumpled shirt, and at first glance, it looks like he’s been handcuffed by the policeman who’s hooking his arm. That’s a solid visual metaphor for a story about a man being prosecuted for murder.

But while it’s the stuff of a publicist’s dreams, the photograph was a happy accident. “I was plunked down on the floor, and it was just the luck of me capturing the stuff that was unfolding around me,” said unit photographer Michael Becker. “Sometimes, you get lucky enough to capture a moment that draws you into what’s going on.”

More from IndieWire

'Hacks' Knows Good Comedy Looks Effortless - and So Does Its Makeup Design

How 'Palm Royale' Showrunner Abe Sylvia Made a 'High Queer' Political Apertif for Apple TV+

That’s how it goes in his business. Whether they’re used for advertising or as the thumbnail on a streaming service menu bar, episodic photographs can define the public’s impression of a show, yet they’re often captured on the fly.

“I love to really dive into the scripts first to try to highlight certain beats that I think would make for interesting moments,” said Jake Giles Netter, a unit photographer on the third season of “Hacks,” currently streaming on Max. “But sometimes that goes out the window completely when you actually get to see a rehearsal and see the actors’ blocking. The key is to anticipate moments where you can, but also be open-minded enough to ‘shoot like jazz’ and improvise when the time comes.”

However, a unit photographer has to improvise within tight parameters. “On a scripted series, you have motion cameras that are in place, and everything is perfectly blocked and choreographed for those lenses,” Becker said. “You have to find your hole in there without being in an actor’s eyeline and without disturbing the crew and the talent. And you can get in trouble. You can get called out if you’re if you’re moving and distracting an actor or something like that.”

Before he started shooting film and television, Warrick Page was a conflict photojournalist in the Middle East and Asia. He told IndieWire the two experiences weren’t so different. “There’s no way to work in those kinds of regions and on those kinds of stories unless the people you’re photographing accept your presence and welcome you,” he said. “I apply the same thing to a set. When people see you actually care about who they are, what they do, and how they do it, then your world is going to physically open up. When people make room for you, then you can work a scene and you can find the images.”

Case in point: When he was photographing “Winning Time,” HBO’s series about the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1980s, Davis learned to bob and weave among the crew, and he learned to sense when the actors were comfortable enough to have an extra camera hovering around. “There were four other cameras rolling on this wild scene of celebration and champagne popping and everything, and I realized that with a particular angle, there might be a heartbeat where the other cameras were out of my frame. I managed to thread the needle and get a shot [seen above] suggesting I was the only camera in the room. In those moments you roll the dice, and if you come back with something special, it’s always worthwhile.”

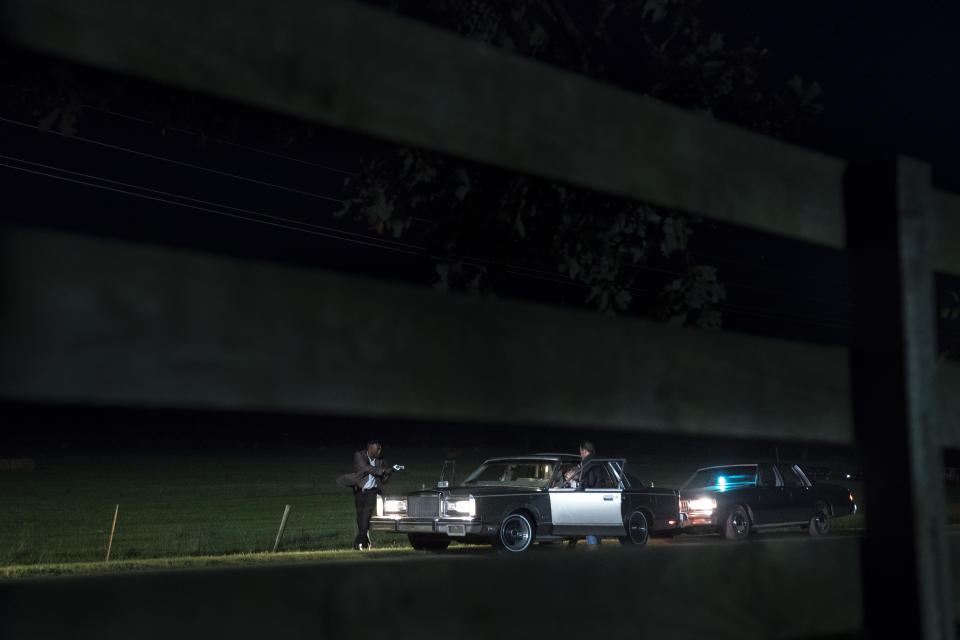

This points to another contradiction in the work: While set photographs are often used as marketing tools, they can double as works of art. Page recalled a shot that he lucked into on the third season of HBO’s “True Detective,” when he wandered away from the set and happened to glance back as the actor Mahershala Ali was filming a stand-off outside a car. “I got this great frame,” he said. “You can see Mahershala, very deep in the frame, his gun brandished and running around. It communicates very clearly that something is going terribly wrong. It would never work for a press photo, because it doesn’t have a close-up of anyone’s face, but I loved the story of that image.”

Even if they’re useless for the press, those artier shots can inspire other creatives. Adam Bricker, who’s been director of photography on every season of “Hacks,” said that still images are essential reference points as a team develops its aesthetic. “Early on in ‘Hacks,’ a lot of my process for figuring out the look of the show, from a lighting and color perspective, was based on the research that I did just pulling stills.”

Images from the films “Judy” and “Behind the Candelabra” were particularly informative as Bricker developed the palette for “Hacks,” which follows aging comedian Deborah Vance as she chases the magic of her glory days. “We were trying to achieve a look that was modern day but also felt a little vintage, like it called back to Deborah’s heyday,” he said. “Looking at those stills was incredibly helpful.”

He cited the website ShotDeck as vital resource for this kind of prep. Created by the cinematographer Lawrence Sher (“Joker,” “The Hangover”), it’s a database of thousands of stills from films and television shows. “Everything is really elegantly tagged,” Bricker said. “If you search ‘stand-up comedian in a theater in warm light,’ an image from ‘Hacks’ will come up, along with images from dozens of other shows and movies.”

Nowadays, Bricker references stills from earlier seasons of “Hacks” to ensure new episodes are visually consistent with what came before. That’s another good example of how a static image can impact kinetic visuals.

And even though some networks occasionally give hi-res screen grabs instead of proper photographs, Bricker stressed unit photographers are invaluable. “They have their own form of artistry,” he said. “They showcase a project in a completely unique way.”

Becker concurred. “If you think about it, we’re telling the story differently,” he said. “Cinematographers are telling it on a timeline, and we have to try and tell a story in a single moment, frozen in time. They’re related disciplines, but they are certainly different.”

Page added, “In some ways, we’re the least important people on the set while the show is getting made, because we don’t have an active role in creating it. But then our images go into the world and influence people. So we’re not a crucial part of the show being made, but we are a crucial part of the show being known.”

Best of IndieWire

The 13 Best Thrillers Streaming on Netflix in May, from 'Fair Play' to 'Emily the Criminal'

The Best Father and Son Films: 'The Tree of Life,' 'The Lion King,' and More

The 10 Best Teen Rebellion Films: 'Pump Up the Volume,' 'Heathers,' and More

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.