The untold story of 14 kids who lost their mother in the crash of Wapiti Flight 402

The children were crowded around a little black-and-white television set, but only half-watching it.

The older Noskiye siblings were sprawled across three worn couches in their tiny living room. The younger ones were on the floor. The Tommy Hunter Show was blaring, but it was hard to pay attention, knowing their father was supposed to be home soon with their mother.

Elaine Noskiye had been in the hospital in Edmonton for weeks, due to complications with her 14th pregnancy.

Her little boy, born months early, had a heart murmur and respiratory difficulties, and had to stay close to his doctors.

On Oct. 19, 1984, Elaine was finally allowed to return home to Whitefish Lake First Nation, a remote reserve about 400 kilometres north of Edmonton.

Her 13 other children couldn't wait to see her.

Elaine boarded Wapiti Flight 402 around 7 p.m. It was supposed to land at the High Prairie Airport, where William Whitehead, her common-law husband and the father of all of her children, was waiting to meet her at 8 p.m.

It was unusually cold, even for northern Alberta in the fall. Snow had come early, coating back roads in a freezing slush that made for slow driving.

The younger Noskiye siblings went to bed. As minutes turned to hours, most of the older ones followed. The eldest daughter, Lillian Noskiye, was 20 at the time. Still awake when the phone rang, she answered.

"The whole world stood still for a minute," said Lillian, who no longer remembers who called. It could have been her father, or an aunt or uncle.

She was told her mother's plane hadn't arrived at its destination. A search party was underway.

"My heart fell to the floor," she said.

It was snowing and visibility was poor as the pilot of Wapiti Flight 402 tried to calculate a landing path without the help of a co-pilot. The plane crashed about 30 kilometres south of the High Prairie Airport. Six of the 10 people on board died, including Elaine, who was 39 years old.

Because the weather was bad, it was the next day before the search party found the fuselage.

'They came back without her'

Wilma Noskiye was eight years old. She knew something was wrong the minute her father returned home.

"They came back without her," she said.

Overnight, the news media had caught wind of the crash, and knew that two high-profile provincial politicians, NDP Leader Grant Notley and PC Housing Minister Larry Shaben, had been on board the plane.

Wilma found herself back in front of the television set, but now couldn't pull her eyes away from it.

"It was scrolling down, naming people that were in a plane crash," said Wilma, who read her mother's name as it went by.

The news rippled through the family.

"It was like breaking apart over and over again," said Lillian, who struggled to explain to her brothers and sisters, one at a time, that their mother wasn't coming home. "It was like I broke in a thousand pieces every time I was telling one of them what happened."

Wilma waited her turn. When it came, she remembers going into the bathroom with her sister, sitting on the edge of the bathtub.

"I knew," she said. "I knew without her telling me."

Then she cried. Cried for her mother and father, for her sisters and brothers.

"I knew she had the other ones to tell," Wilma said of her older sister. "I tried not to stay in there with her too long."

Their mother's message

For years, the Noskiye siblings haven't talked much about their mother. Every time one of them would bring her up, another would break down.

But as the 33rd anniversary of the plane crash approached, Roger Noskiye, who was 22 when his mother died and the eldest child, approached CBC News to tell the family's story. Knowing there was interest, he broached the idea with his sisters and brothers. They agreed it was time.

The siblings, who lost their father in a car accident in 2004, gathered at the farmhouse near Athabasca, where Charlene Jackson (nee Noskiye), who was 14 when their mother died, now lives with a family of her own. It has become a central meeting point for the siblings over the years, most of whom are scattered throughout northern Alberta. On the wooden table in the small kitchen, they carefully arranged the few precious photos they have of their mother.

They're close-knit. They had to be in the years that followed the tragedy. The older siblings took the younger ones into their homes in an effort to ensure that children's services wouldn't get involved. Gathered in the kitchen recently, they looked at each other almost as intensely as they did the photographs, as if wondering how well they really knew each other.

"I think there's a lot of things that we never shared," said Colleen Jobin, who was 18 at the time of their mother's death.

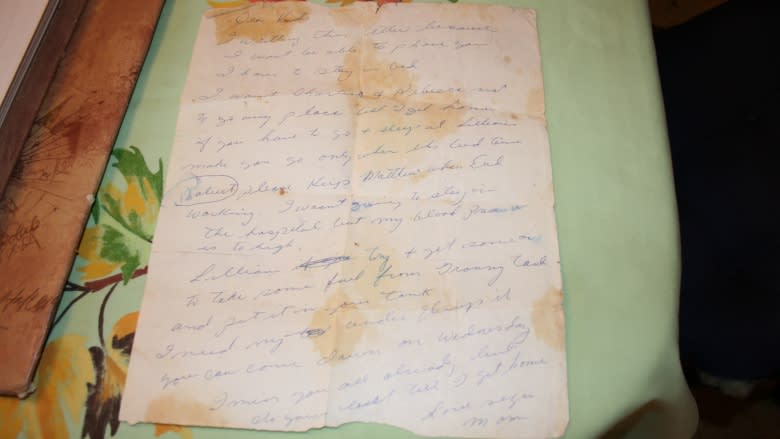

She has held on to the letter her mother wrote from the hospital. Some of her siblings had forgotten about it, or were so young at the time they didn't know it existed. They passed the letter around, and agreed that Roger should read it aloud.

"I miss you all already, but do your best till I get home. Love, sign, Mom." As he finished, Lillian grabbed his hand and squeezed tight. Some of the siblings cried. But Robert Noskiye, who was 16 when their mother died, said he was overcome by a different emotion: relief at finally being able to talk openly about his mother.

"It's a load off," he said. "It has to be the family to close this thing that's been troubling us for years."

Seeking connection

The Noskiyes haven't talked much over the years about their mother's death. But they couldn't avoid constant reminders. Five others — Pat Blakovits, Chris Vince, Gordon Peever, Terry Swanson and Grant Notley, the only NDP MLA in the Alberta legislature — were killed in the crash, and media interest was insatiable. Four people — PC Housing Minister Larry Shaben, RCMP officer Scott Deschamps and the low-risk criminal he was escorting, Paul Archambault, and the pilot, Erik Vogel — managed to crawl out of the smoldering fuselage alive. That became part of the story, too.

"For a while, people would talk about Grant Notley and I'd feel sad," said Wilma. "But then there would always be the lingering thought, 'Well, my mom was on there.' It hurts a little bit."

In 2015, Grant Notley's daughter, Rachel, led the party he helped build to victory as Alberta's first NDP government. Wilma reached out to her by email.

"I just wanted to send my condolences, and I'm letting her know that I share the same kind of grief," said Wilma, who was surprised when a reply from the premier's office landed in her inbox.

The premier responded: "I am sorry that you, too, know the pain of losing a parent. There are no words to adequately describe the experience."

For Wilma, the six-line note from Rachel Notley was enough.

"I just felt like it was mutual, you know, because it was her parent, too," Wilma said. "We share that sorrow."

Wilma said her mother never minded being low-profile. But she said the opportunity to tell her story was meaningful.

"I think it will finally bring a little sense of closure and acknowledgement, to tell our story, that our mom was there, too," she said. "We were part of that story."

'She did it all'

Elaine Noskiye made time for each of her children. Despite long days doing chores and tending to her family, Elaine usually kept her long hair tidily swept back in a ponytail, and often wore a blouse and dress pants.

Crystal Jackson (nee Noskiye), just six years old at the time of the tragedy, used to follow her mother back and forth between the stove in the kitchen and the wringer washer on the porch. If Elaine wasn't preparing food, she was doing laundry, gardening, sewing, cleaning, always something.

"She did it all," Crystal said. "I don't know how."

A deeply religious woman, Elaine prayed for her children. Sometimes, they heard her sobbing quietly as she asked God to watch over them. She wanted the best for them, and they knew that. She hoped they'd achieve their dreams, and was convinced they'd be best equipped for life if they were educated.

"She always made sure we went to school," said Debbie Laboucan, who was nine when her mother died. With two older siblings already in college, she knew even then that she was supposed to be striving for something better.

Elaine was there for her children when it counted most. When Wilma needed someone to help stock the imaginary shelves of her imaginary store. When Robert wanted company while he sat in the parked car in the driveway and listened to music on the eight-track. Lillian and Colleen had moved out on their own; Colleen to attend college, Lillian to live with her common-law husband, so that they could raise their young son together. Elaine made a point of talking regularly to both girls on the phone.

"Her greatest thing was to keep the family together, taking care of them," Lillian said. "So naturally, that was my first instinct."

Keeping the family together

Elaine Noskiye was the love of William Whitehead's life. He planned to marry her, but with a house full of children, they never found the right moment. Then the chance was gone.

William tried his best after Elaine died, said Debbie. But he was overcome with grief.

"I just remember him crying and crying," she said.

William was determined to keep his children together, though he had to make concessions. Lillian, who was living across the road with her own family, took four of the younger girls (Debbie, Wilma, Crystal and Wendy) into her home. Their mother's sister, Laura Laboucan, lived nearby on the reserve. She raised the new baby, Sandy Lee, as her own.

The other older siblings, Roger and Colleen, had been studying off-reserve when their mother died. Both dropped out of college not long afterward. Shattered, they wanted to be home to help, but couldn't bear to stay on the reserve. They knew their mother wanted them to be educated, and eventually returned to school.

However much William loved his family, he struggled with alcoholism — especially after Elaine's death. Robert, Charlene and Rebecca, who was 12 years old, stayed with their father to help him raise the younger boys (Gareth, 4, Kelly, 3, and Darren, 2). Charlene remembers coming home from school on Friday nights to a house full of drunks. With Rebecca's help, she said, they'd kick them out and take care of the toddlers.

Despite the turmoil, Crystal was thankful for the way things were.

"The one miracle I always think about, and know that it was probably because of my mom's prayers, is that we didn't get separated," she said. "We weren't put in the system. Home life wasn't always so great, but somehow we always managed."

Back on track

Two and a half years later, in the spring of 1987, tragedy struck again. The family's home, where their mother's few belongings remained, burned to the ground.

Debbie, who was living with Lillian, remembers her father and siblings running from the fire, seeking refuge from the flames that consumed memories of their mother.

Not long after, Debbie left the reserve. She wanted to attend high school, and Whitefish Lake, back then, only offered classes up to Grade 9. Debbie moved around northern Alberta, living a year here, a year there, with older siblings, who had previously done the same before settling down. There was an element of culture shock. By 15, she was flailing. She needed her mother to tell her everything would be OK.

"I cried when I forgot how her voice sounded," Debbie said. "I think that's when I felt the most lost."

When she had a child of her own at 18, she remembered what her mother would have done.

"She had a strong will," said Debbie, who got her life back on track and raised her daughter, first with the help of Lillian and other siblings. She completed her addictions worker diploma.

There are still moments when Debbie wishes she could talk to her mother.

"With every important date in my life, I wish she'd been there," she said.

'They don't need to worry'

The siblings have struggled with their own demons. But if their mother could see them now, together and happy, "she'd be crying tears of joy," said Lillian, an addictions worker at the Whitefish Lake health centre. "Her wish was for everyone to grow up and be strong."

Roger, an artist, Robert, a carpenter, Rebecca, an accountant, and Debbie, who works alongside Lillian, all live on the reserve. Wilma, who does payrolls, lives near Charlene's family farm, just outside Athabasca. Life's journey took Crystal, an educational assistant, and Gareth, who works in hotels, further away. Both now live in New Mexico with families of their own.

Finding their way has been a challenge, but the siblings are finally starting to feel comfortable enough to talk about the obstacles they've overcome.

Colleen had suicidal thoughts after her mother's death. Even now, she cries when speaking about that time in her life.

"We're only human, but we did our best to help each other to survive," said Colleen, who also found strength in memories of her mother. "Her legacy was that in her short 39 years of life, she did a wonderful job all those years, taking care of us, loving us, being a real good example of what a mom should be."

Wendy, the second youngest, was barely a year old in October 1984. She doesn't remember her mother.

"I'd always ask my sisters," she said. " 'How was mom? What was she like? What would she do in this situation?' "

A single mother to a six-year-old girl and seven-year-old boy, Wendy is more like her mother than she knows.

"They help me get a sense of meaning in my life," said Wendy, who wants to go to college and study interior design.

The younger siblings have relied on the older ones to help them grow up. Crystal said they have a bond most people don't understand.

"That's what my mom brought to us when she was here," she said. "But even more so when she left."

Kelly, a musician, and Darren now live in the Edmonton area.

After their dad died, Darren, still on the reserve, spiraled downward. He was drinking heavily and had blackouts. Debbie and Rebecca intervened. Debbie, who was in Edmonton at the time, lent him her car, helped him find work and save money. He's been sober since, working as a pipefitter, and has a family of his own in the suburbs. He later helped Sandy Lee, a carpenter in Grande Prairie, find his footing

Darren said he wishes his parents were around to see them now.

"They did good with us," he said, his voice breaking with emotion. "They don't need to worry.

"I would tell them that we're doing just fine."

roberta.bell@cbc.ca

@roberta__bell