New vaccine targets pneumonia, blood poisoning, meningitis among children in Canada's North

Federal researchers have collaborated to develop a preventative vaccine for a potentially deadly bacteria that causes pneumonia, blood poisoning and meningitis in children and affecting predominantly children in northern and Indigenous communities.

Scientists with the Public Health Agency of Canada first identified Haemophillus influenza Type A (Hia) infections in the mid-2000s in Winnipeg, Edmonton and Montreal hospitals. Hia is not the common flu — which is caused by a virus, not bacteria.

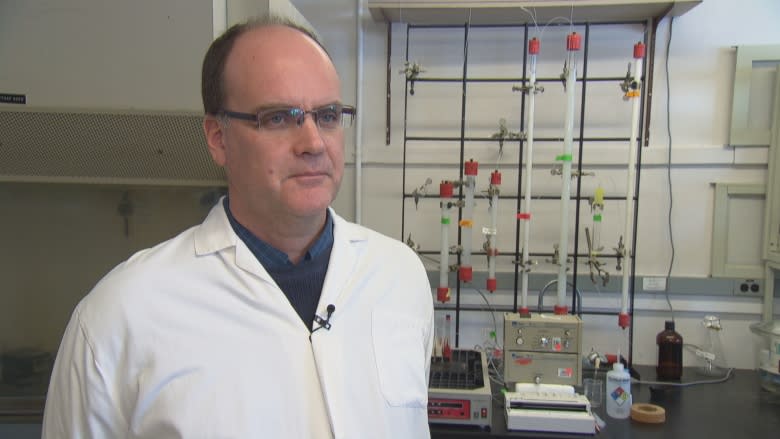

Hia has become more common since then, evolving into an emerging public health concern among children under five and for adults whose immune systems aren't working properly, said Dr. Guillaume Poliquin, the senior medical adviser for the Public Health Agency of Canada at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Winnipeg.

About 500 people are exposed to Hia every year, and about 10 per cent of those die.

"It can spread anywhere in the body and can cause things from pneumonia to skin, soft tissue and bone infections, but the complication we fear the most is when it gets to the lining of the brain and can cause … meningitis," Poliquin said during a recent tour of the Level 2 lab.

Poliquin bridges basic science and hands-on medicine. He is an infectious disease pediatrician who works in northern communities and has seen the devastation this bacteria can cause for patients and their families.

Children infected with meningitis can't be treated in their home community, so they have to be medically evacuated to hospitals, where they spend weeks on intravenous antibiotics.

"That means displaced child, displaced family in a foreign community away from all your support networks, and the story doesn't end there. Meningitis often has long-term impacts on the child's development so that means back and forth travel for years. The impact is immediate and long-term," Poliquin said.

"As to why specifically we're seeing it most in Indigenous populations at this point, it's an area of ongoing research. Certainly the living conditions in the North, crowding, poor access to nutritious foods, probably contribute to it, but we don't know for sure."

Dr. Raymond Tsang's Winnipeg-based research team identified the Hia Type A bacteria as the one responsible for the cases they were seeing.

They isolated the piece of the bacteria most vulnerable to a vaccine and sent that to the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) in Ottawa.

Scientists there developed a vaccine using specialized chemistry and technology. It involves engineering a molecule called a carrier protein that they attached to the bacteria, making it easier for the vaccine to recognize and generates a stronger immune response.

It was found effective in tests on mice and rabbits.

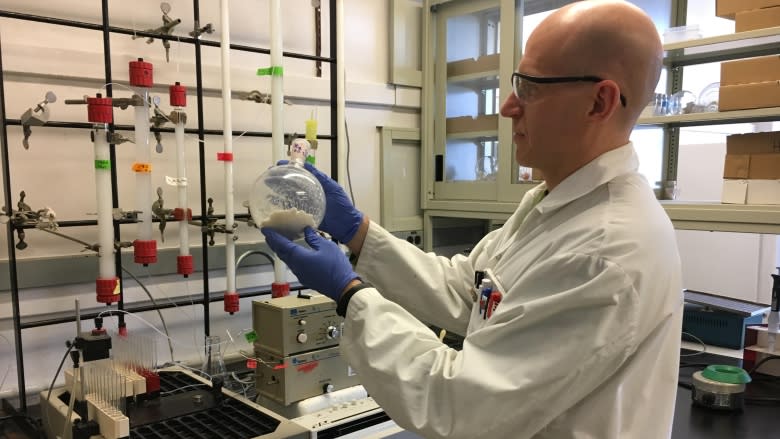

"It looks very good," said Andrew Cox, senior research officer at NRC.

"The fact that it kills all the strains in our collection from different geographical locations establishes that we believe it would be a very good vaccine."

Antibiotics can treat Hia Type A infections, but this is the first vaccine developed to prevent it. A vaccine has been effective in preventing meningitis caused by Type B — in fact, it has almost disappeared as a result of immunization — but there's no cross-protection for Type A.

NRC recently gave the licence to manufacture the Type A vaccine to Vancouver-based InventVacc Biologicals Inc. The financial terms related to the licence agreement are confidential and cannot be disclosed.

However, the actual technology and intellectual property is still owned by the Government of Canada. Now, the company is looking for federal funding to conduct clinical trials.

"This particular disease isn't a commercially lucrative disease. It's only a niche population that seems to be suffering, so big pharma aren't interested, unfortunately, because they're not going to make a whole heck of a lot of money on it," Cox said.

He said researchers have reached out to the U.S. Centre for Disease Control to see if they can collaborate. Hia has been found in Indigenous populations in Alaska as well.

"To me, the bottom line is that Canadians are currently dying of something which we could prevent and I think the government has a responsibility to their citizens to look after their own. And so this is an opportunity to do just that."

Challenging with limited population

It will require public funding, agreed Dr. David Scheifele, a retired pediatric infectious disease specialist in Vancouver who founded the IMPACT surveillance network of pediatric hospitals across Canada.

"So in the northern parts of the provinces and in the territories it's almost as frequent or as frequent as Hemophilus Type B was back in the the bad old days," he said.

"The disease it causes is just as bad as Type B disease was back then. So causing meningitis, causing pneumonia, causing sepsis, causing death."

There may be an opportunity to work with governments in other countries, including the United States, Scandinavian countries and even Brazil, Scheifele said.

"It's not the sort of vaccine that you would want to administer to entire populations like all Canadian children. It would have to be a more targeted population. Like children in Nunavut, in the other territories maybe in the northerly Aboriginal communities but you know in total these are a relatively small population," he said.

"So any profit to be made on a vaccine with limited sales would be negligible … it would certainly be a very helpful vaccine to develop, but it's going to have to be done primarily by the public sector funded by governments and perhaps charitable foundations like the Gates Foundation."

'We're not rats'

Indigenous leaders say they welcome anything that will improve the health and quality of life for people in northern communities.

However, they said they need to be consulted about clinical trials involving their people.

The chief of Barren Lands First Nation in Northern Manitoba said he hopes the vaccine is tested and approved for use in humans before it's sent to communities like his.

"Prevention is always very important," John Clarke said, adding it's a burden to medevac patients south for treatment of pneumonia and meningitis.

"[But] we're not rats. They should test it on somebody else before they bring it to us. We're from the Far North, our health care has not always been that great, but that doesn't mean they should throw anything at us that they want to."

As chief, Clarke said he would want to know if any of his people are part of any clinical trials — partly to make sure they're providing informed consent. People in his community speak English, Cree and Dene.

'Hand-in-hand'

"As long as there's actual consent and we know what's coming, what it's for, and who's getting it. … I'd leave it up to the parents but for myself, if it was going to be brought to my kid or grandkid, I'd want to make sure that it's been proven or tested elsewhere," Clarke said.

The NRC's Cox said work is already being done to work with Indigenous communities on clinical trials, "but I emphasize, we'd only do this hand-in-hand with them, with their support and knowledge of what's involved."

A statement provided by Health Canada adds: "No trials in Indigenous communities would happen without express interest from those communities, along with their input into the design and implementation of the trial. Furthermore, clinical trials for this vaccine will adhere to the ethical guidelines for research studies that impact First Nations communities, as articulated by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research."

If approved by Health Canada, the vaccine could be available for use in Canada by 2022. The hope is to get it to children under the age of one, as part of their first vaccinations.