As Vancouver tent city expands, some neighbours voice support for campers' demands

As the tent city at Strathcona Park expands, some neighbours are voicing support for a new list of demands the campers have issued to the city, as well as the provincial and federal governments, including permanent housing for all.

In three weeks, almost 150 tents have popped up at the camp, which campers call KT, short for Kennedy Trudeau — referencing the mayor of Vancouver and the prime minister of Canada.

The campers moved to Strathcona Park after Vancouver police enforced an injunction granted by the B.C. Supreme Court against another camp on Port of Vancouver land next to Crab Park.

Their list of demands, outlined in a news release, includes "permanent housing for all, an end to the cycle of displacement, and repatriation of unceded Indigenous land."

The new camp takes up about a quarter of the park in East Vancouver and edges on Cottonwood Community Garden, which neighbours have been building for almost 30 years.

About 95 per cent of the gardeners support the new camp, according to garden president, Beth McLaren.

"I mean, what they're asking for does not seem unreasonable to me," McLaren said from the garden.

"Some kind of permanent location, they want to go back to both parking lots in Crab Park and are asking for things like water and toilets and the basics."

McLaren says she shared some of the gardeners' needs — including access to a wood chip pile and a clear entrance point to their garden — in a recent meeting with camp organizer Chrissy Brett.

Gardeners have provided campers with a water hook-up, wood chips for the camp's fire, and herbs from the gardens.

'They seem well organized'

But not all neighbours are in favour of the camp.

Theo Lamb, executive director of the Strathcona BIA, told CBC's Early Edition she is worried about crime and even violence that the camp could bring.

However, McLaren said there was already crime — including break-ins, fires and open drug use in the gardens — before the campers arrived.

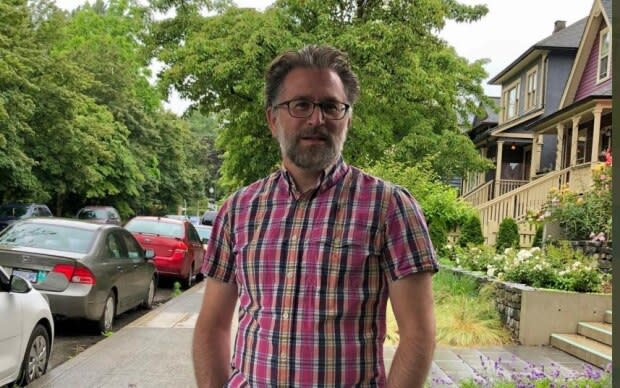

"The way they've set up, it's clean, they seem very well organized," said neighbour William Azaroff, who also leads a non-profit housing group called Brightside Community Homes Foundation.

Azaroff said he attended a free barbecue the campers put on for the neighbours last weekend, where they held information sessions about their intentions — namely that they want to find a new permanent home.

"If you told me a year from now that camp was double the size and fully entrenched and not going anywhere, I'm not sure that's a good outcome for anyone and it's not what they want," Azaroff said.

Campers still trying to get housing

In late April, B.C. enacted a public safety order to move homeless people living in encampments into hotels in Vancouver and Victoria during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The province identified 686 hotel and community centre spaces in Vancouver to house the city's homeless until more permanent housing is made available.

But not everyone made it into those spaces. One of those is James, who didn't want his last name used since he is still trying to find housing.

He has cancer and is a veteran.

"It's been a really rough go, I've been homeless now for three years," he said from the camp, where he now lives.

He said he has been on the B.C. Housing list for 10 years and looks for housing every day.

The provincial government has said there is not enough affordable housing stock available.

Shane Simpson, minister of social development and poverty reduction, said in a statement that the province is asking the federal government "to step up and contribute capital dollars for acquisitions, modular housing and other long-term solutions."

Advocate says tent city more than housing

Advocates like Anna Cooper of Pivot Legal Society, say tent cities offer people a sense of community they may not feel elsewhere.

She said living on the street — in doorways or under bridges, for example — is not safe, while single-room occupancy hotels (SROs) sometimes come with violence, unsafe drinking water and bugs.

Cooper added that people living in SROs have not been allowed visitors due to COVID-19, making it challenging for drug users to safely inject with someone watching over them.

"Some people, as long as they're forced to live outside, will feel safest in a tent city community," Cooper said.