Why free trade is John Crosbie's greatest national legacy

When Brian Mulroney stands Thursday afternoon in the Anglican Cathedral in St. John's to say goodbye to John Crosbie, the former Progressive Conservative prime minister will be saying adieu to the man who raised the curtain on the Mulroney government's signature achievement: free trade with the United States.

What's remarkable is that Mulroney was once against free trade. He actually fought John Crosbie over the issue during the fateful 1983 PC leadership.

In Crosbie's 1997 memoirs, No Holds Barred, it's clear the St. John's politician was a free trader from way back — before Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949.

"Newfoundland was always a free-trade area. We were a little country that traded with everyone, worldwide.… To us, free trade was just a matter of common sense."

Don't forget, Ches Crosbie — John's father, in this case, not his son, who currently leads Newfoundland and Labrador's PCs — launched the Party for Economic Union with the United States. Despite some modern-day myth-making, this was not an option when Newfoundlanders voted in two plebiscites to decide the province's future.

John Crosbie writes: "As a teenager at the time, I supported Dad's campaign, and ever since I have held firmly to the view that free trade makes every bit of sense for all of Canada as it made for Newfoundland in the late 1940s."

Mulroney did not grow up with these beliefs and would not be converted to the merits of free trade until 1985. This became particularly fascinating when the difference of opinion between the two men exploded into the open during the PC leadership battle.

"I made free trade the policy centre-piece of my leadership campaign.… The issue helped to set me apart from [Joe] Clark and Mulroney," Crosbie wrote.

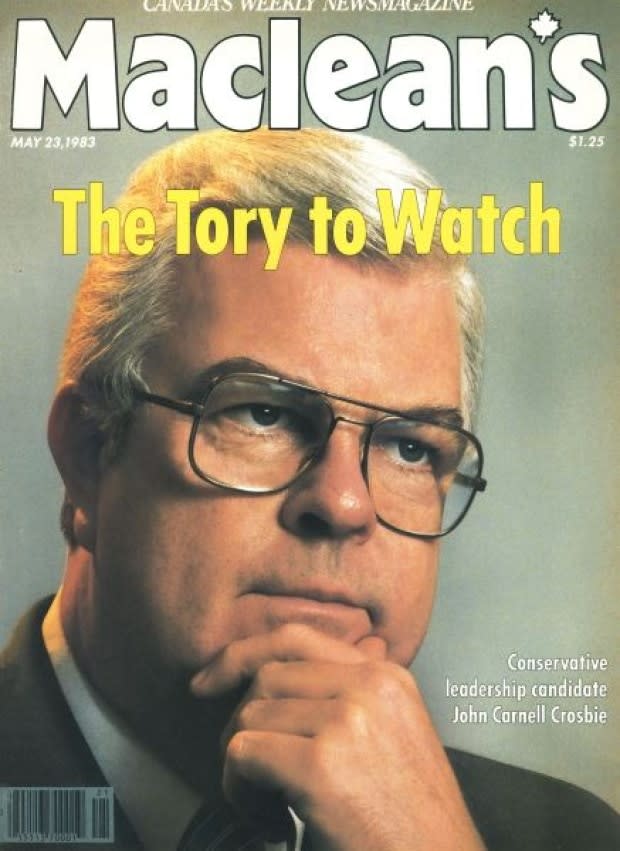

Maclean's magazine had dubbed Crosbie "the Tory to watch," while the Globe and Mail, financial newspapers and Bay Street started to praise the Newfoundland MP's decision to inject a gutsy policy issue into the race.

CBC will carry special coverage of John Crosbie's funeral Thursday, starting at 1:30 p.m. NT (noon ET). It will air on CBC News Network, CBC Television and Radio in Newfoundland and Labrador, on CBC Gem, the CBC News app and CBCNews.ca, and on CBC N.L.'s YouTube and Facebook channels.

If anything strikes fear into ambitious mainlander politicians — like Mulroney and Clark — it's when the Toronto-based establishment media starts extolling fresh ideas of an opponent.

Crosbie, as usual, was stirring things up.

'A significant dilemma'

In Mulroney's memoirs, the former PM noted: "When he announced that he was entering the race (on the same day I did), John came out in favour of free trade with the United States. For me, this move represented a significant dilemma."

As president of the Iron Ore Company of Canada, Mulroney did not believe Canadian companies could compete against American counterparts.

John Crosbie did. If they couldn't, so be it.

Mulroney wrote his team "acknowledged that Crosbie's support for free trade was a powerful idea that distinguished him from everyone else and made him an attractive candidate in parts of the country where he needed to gain support."

Mulroney's strategy was to ensure the leadership fight would come down to a battle royale between him and Joe Clark. He did not want to be plagued by any free trade controversy for the rest of the campaign.

So he came out swinging:

"Now there's a real honey — free trade with the Americans," I told the Globe & Mail," he wrote. "Free Trade with the U.S. is like sleeping with an elephant. It's terrific until the elephant twitches, and if the elephant rolls over, you are a dead man."

Crosbie's memoirs also noted the future PM's fear-mongering: "Mulroney warned that 'opening the floodgates' by embracing free trade with the Americans would endanger Canada's economic and political sovereignty."

Mulroney opted to campaign on improving relations with the Americans and creating a "close, productive relationship with the United States, that does not however include free trade," he wrote.

'More direct and forthcoming'

Mulroney was so focused on zeroing in and defeating Joe Clark, he strategically sidestepped the free trade policy debate by, like Clark, denouncing Crosbie's stance. Mulroney later admitted the move was pragmatic and disingenuous.

"Still, it was a less than honest position for me to take. Crosbie was more direct and forthcoming than I was at the time."

Less than five years later, on Jan. 2, 1988, Mulroney signed the Free Trade Agreement with U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

The Macdonald Commission on Canada's economic future, chaired by former Liberal finance minister Donald S. Macdonald and released in 1985, suggested there were great opportunities with free trade. Crosbie believed this royal commission is what changed Mulroney's thinking to finally match his own.

A few years ago, I had the chance to interview Crosbie at his home for several hours. I asked him then if he was responsible for putting free trade on the Canadian political agenda. He repeated his lifelong belief in free trade, but he gave all the credit to Mulroney.

During the week-long obituary deification of Crosbie (which he would have hated), much has been made about his role in assuring Hibernia and the riches of offshore oil, about shutting down the cod fishery and mounting a major federal relief program, and eventually declawing Joey Smallwood, whom Crosbie viewed as a corrupt and incompetent tyrant.

But for his country — and also his home province — Crosbie viewed free trade, NAFTA and his own role in the creation of the World Trade Organization as his supreme achievement.

"If the pundits ever stop kicking us around … they will record that our greatest achievements lay in the field of trade. These accomplishments were the result of the inspired leadership by Prime Minister Mulroney, his willingness to risk extreme unpopularity in parts of Canada."

Tapped for a job he was made for

To sell the free-trade deal, Mulroney needed someone he could trust, a closer.

Two months after the the deal was signed, he shuffled his cabinet on March 31, 1988 — 39 years to the day Newfoundland joined Confederation. And who did he make his minister of international trade?

The former teenager who had believed economic union with the U.S. was preferable to joining Canada, the St. John's townie who morphed into federal politics while slowly endorsing the benefits of being Canadian, the very man Mulroney had opposed just five years earlier because he said free trade was wrong.

Crosbie's advice to fearful Canadians — the ones he described as "CBC-type snivellers in Toronto" and "professional anti-Americans" — was to take a lesson from Newfoundland history about dealing with Americans.

"I'm not concerned that they are going to dominate me intellectually or that somehow their culture is going to crush Canadian or Newfoundland culture," he wrote.

"If Newfoundland could survive political and economic integration with mainland Canada without losing its distinctive culture, then Ontario and the rest of Canada could survive economic integration with the United States."

Despite the rise of Donald Trump (and I have come to learn that Crosbie in his last few years was certainly not a fan) and a global shift away from trading blocs and trade agreements, Canadian political leaders of all stripes still like to brag that more than a billion dollars of goods and services cross the US-Canada border every day.

The history books emphasize that Mulroney signed the deal with Reagan.

But it was John Crosbie who drafted and introduced the legislation and travelled from coast-to-coast-to-coast to sell and implement the deal; he took fire and got into shouting matches at raucous public free trade meetings and it was left to him to manage the nervous nellie premiers who feared free trade.

Brian Mulroney is credited with bringing Canada into a pact with its largest trading partner.

But it was John Crosbie who did the heavy lifting.

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador