Why do so many small towns have a Chinese restaurant?

Stream Good Question, Saskatchewan on CBC Listen or wherever you get your podcasts.

Venessa Liang thought her family's situation — being the only Chinese people in a small Saskatchewan town and running a restaurant — was unique.

"It honestly felt very alone growing up," she said. "It felt like we were the only ones."

Her family owned Ben's Place in Colonsay, a town of approximately 400 people about 55 kilometres southeast of Saskatoon.

Liang said the family lived in the restaurant until they could afford a separate home. But even after moving out of the restaurant, most of her childhood was spent there.

"It feels like I grew up in the restaurant, if I'm being honest," she said. "So most of my memories are there."

It wasn't until Liang was older that she realized restaurants like Ben's Place dotted the Canadian landscape, not only on the Prairies but coast to coast to coast.

Liang asked the CBC podcast Good Question, Saskatchewan about Chinese restaurateurs in small towns.

LISTEN | Why do so many small towns have a Chinese restaurant?

The answer dates back to the first wave of Chinese labourers, who came to Canada to participate in the gold rush and build the railway, according to Ann Hui, author of Chop Suey Nation: The Legion Cafe and Other Stories.

For her book, Hui travelled the country to interview Chinese restaurant owners in small towns.

Hui said that as Western fears about the Chinese population grew, many were forced into small communities to work in low-paying jobs, often in restaurants, convenience stores or laundromats.

"There were all of these kinds of laws that were put in place to really try to prevent Chinese people from entering mainstream society and so that left very, very few options for those Chinese migrants," she said.

Lui said this is why so many Chinese-owned restaurants sprang up in small towns, primarily close to the rail line.

"Maybe they had a little bit of success and were able to sponsor or to bring over another relative from China," she said, adding that these restaurants often supported several family members over many years.

That trend has continued.

"Restaurants are often a starting point. [They are] a really great vehicle for newcomers to this country."

Hui outlined a few reasons why running a restaurant makes sense for an immigrant: you don't need to speak much English, it doesn't require a formal Canadian education and it can often support an entire family.

Hui's reporting on the rural Chinese restaurant landscape resonates with Liang, who now lives in Saskatoon.

"That small town was [my parents'] only chance of making it with what they had, which was very little," she said.

"So many individuals and couples did that and made their livelihood out of that."

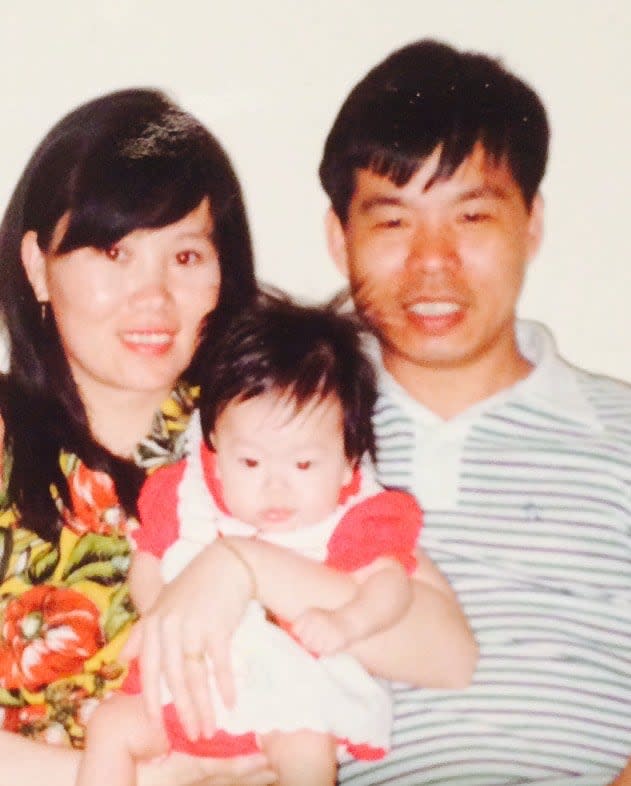

Venessa Liang's parents Muling Liu, left, and Ben Liang pose with Vanessa when she was a baby. (Submitted by Venessa Liang)

Hui said she hopes the unique stories of each restaurant deepen Canadians' understanding of their country's history.

"I really wanted to make it clear that these restaurants are very much a national phenomenon," said Hui.

"I think gaining an understanding of the history of these restaurants — the long history of discrimination and really explicit racism that are at the heart of why these restaurants exist and in some ways why they continue to exist — I think that is so important to understand."