Why this Mexican couple with 3 Canadian-born children faces deportation

Last December, returning from the Dufferin Mall, Nora Trueba saw immigration officials on her front porch, arresting her husband, Israel Ochoa.

"Oh my god, I was in shock," Trueba recalled. She watched as officials pinned Ochoa's hands behind him and led him away. Her youngest son, Kayden, four, called out, "Amor, Amor," Spanish for "love" and the children's nickname for their father.

Their eyes meeting, Ochoa signaled silently to Trueba to keep quiet and Trueba desperately began singing a Christmas carol to distract her little boy, terrified the officers would arrest them all.

In the U.S., Republican candidate Donald Trump's promise to forcibly remove 11-million illegal workers and build a wall along the Mexico-U.S. border has put the fate of migrant workers like Trueba and Ochoa at the forefront of the election campaign. But we hear far less about undocumented workers in Canada. In reality, Mexican people are a growing part of Toronto's workforce, in bakeries, restaurants,and cleaning jobs. Every year, thousands are deported.

For Trueba and Ochoa, that December evening was the beginning of the end of 11 years in hiding.

They had come to Toronto in the spring of 2005, newlyweds on a honeymoon from San Salvador Atenco, near Mexico City. Back home, there were violent mass protests over the government's bid to expropriate land from impoverished peasant farmers to build an airport — tensions that exploded a year later in hundreds of arrests and allegations of human rights abuses by state police.

Fearing for their safety, the young couple decided to risk staying in Canada, spending long hours cleaning restaurants after midnight, attending ESL classes during the day and becoming part of their neighbourhood — careful all the while not to draw the attention of officials.

During those 11 years, the couple had three children, all of whom attend a local school around the corner from their home, which is not far from the Dufferin Mall.

After Ochoa's arrest, neighbours stepped up to help. One of them took in Trueba and her children and found her a lawyer. Another neighbour, together with their landlord of 11 years, paid Ochoa's $5,000 bail along with a $10,000 bond.

Three weeks later, Trueba turned herself in and applied to stay in Canada on humanitarian and compassionate grounds. Days later, Ochoa was released. They were issued year-long work permits but by July, the couple's application to stay was rejected. Ochoa recently received a deportation order in the mail.

A 2009 CBSA (Canadian Border Services Agency) study of detentions and removals shows that year the federal agency deported 4,623 Mexicans.

CBSA doesn't include Canadian-born children in that count because it has no authority over Canadian citizens. Children are allowed to stay if parents can find a guardian to look after them, or turn them over to the Children's Aid Society. In reality, almost no one leaves their children behind.

Trueba hasn't yet been served her deportation order but if her husband goes, she and the children go with him.

"No, I can't live separate with my family," said Ochoa, "I can't. We were looking for an opportunity to live together in this country."

"And that's the prayer that we have in our family," Trueba added. "That's why we're asking for an opportunity. If this is the opportunity to be the voice of all of the families that are having the same situation like us, even if it doesn't change my situation I would like to be part of help others to change the system."

Trueba and Ochoa have bought their airline tickets to return to Mexico. But Trueba says they will appeal the deportation from Mexico.

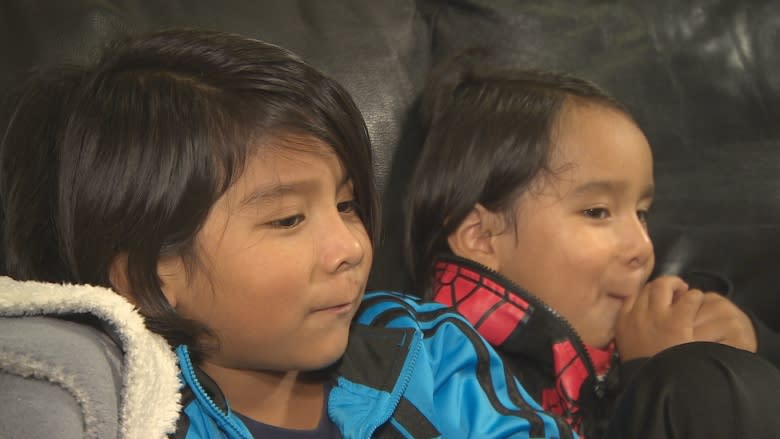

As for their eldest son, asked about his daily routine, Carlos Ochoa describes a morning of "easy math," games and recess, activities familiar to any Canadian nine-year-old, except for one detail.

"When we sing O Canada," said Carlos, "I pray with God that my parents could stay here."