'Willie' provides a glimpse into the future of inclusion in hockey

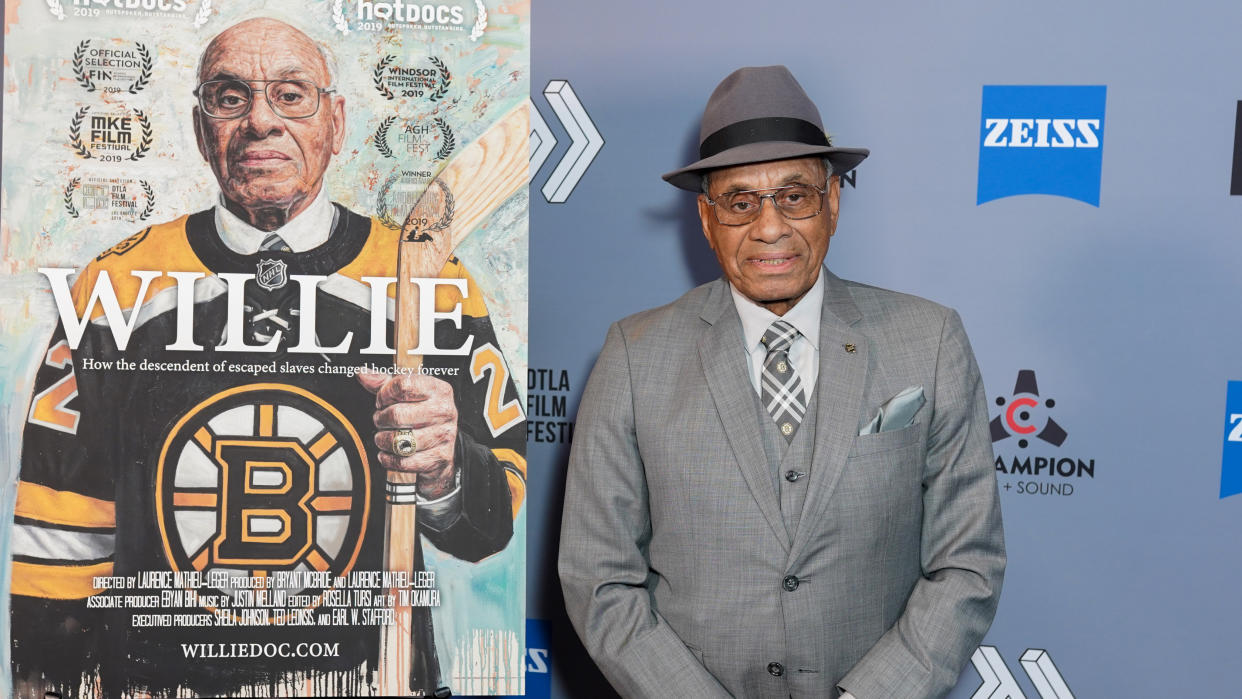

TORONTO - During Black History Month, Demand Films put together a nationwide, one-day screening of Willie, a documentary on Willie O’Ree, the first black player in NHL history.

O’Ree is often compared to Jackie Robinson—a comparison that he initially disregarded, then grew more comfortable with as time marched on—as the film illuminates his pathway to the league, his life, and his bid for the Hockey Hall of Fame among other themes.

In a year where the culture of hockey has been confronted with its own racism—namely through Don Cherry’s firing at Sportsnet and Akim Aliu exposing a pattern of racial abuse from Bill Peters—I attended the screening hoping it’d provide a lens into where hockey can stand to improve on inclusion, race relations and how the sport can become more accessible.

Willie is stylistically divided into three themes: how his hometown of Fredericton, New Brunswick shaped his early life, how he fought through racial abuse throughout his career and how his advocacy emboldened a legion of black players in the NHL and NWHL, along with those outside of the professional ranks where he works with grassroots organizations in underfunded communities.

The film starts by drawing parallels from O’Ree to Robinson and the former explains how he didn’t intend to become the first black hockey player, but that as a black man, he merely wanted to make it to the NHL.

Perhaps it would be crude to point out that Robinson submitted a significantly better playing career, winning NL MVP in 1949, along with six consecutive All-Star appearances—and initially I thought that would be worth exploring further.

Once it became clear, however, that it’s a comparison that O’Ree never makes about himself, and how people merely use it to illustrate the pathway he carved for so many other black hockey players, I realized it’s not worth dwelling on. O’Ree’s impact on hockey is indelible and the generations of players he’s inspired is a testament to his career.

Robinson serves as O’Ree’s contemporary, breaking into MLB a decade before O’Ree first suited up with the Boston Bruins. O’Ree almost followed Robinson’s path, weighing hockey and baseball as equally viable options. However, O’Ree’s life was profoundly shaped by the deeply entrenched racism he faced in Georgia under the Jim Crow era while trying out for a Milwaukee Braves affiliate, which caused him to select hockey over baseball.

O’Ree is a local hero in Fredericton. He says there he felt insulated from the racism he faced in Georgia, and throughout his playing career across various stops through North America. O’Ree’s endless charisma is on full display among friends and locals who always rooted furiously for his inclusion into the Hockey Hall of Fame. In one of the film’s most touching moments, O’Ree stacks all his cell phones on a table while waiting for a call from the Hall, as his friends anxiously await the decision nearby, ready to throw a party in his honour.

During a brief lull in the film, O’Ree states “hockey is for everyone” which is also the title of the NHL’s initiative to eradicate racism, sexism and homophobia from the league and the game’s culture.

The NHL implemented its first Hockey Is For Everyone Month three years ago, and it’s something O’Ree has been proud to participate in. Hockey Is For Everyone, however, has been derided by people of colour, people who identify as LGBTQ+ and other actors outside of hockey’s core demographic for only addressing these problems on a surface level, and I wrote about this extensively last summer.

Upon further reflection, it isn’t a failing of the film, and certainly not of O’Ree’s, to singularly provide a template on how to eradicate these problems from the sport. O’Ree’s tireless advocacy, work with grassroots communities—particularly in Harlem, New York—and his mission to work with young people so they don’t have to endure the hardships he faced during his career should be his underlying legacy. In many ways, O’Ree is a Canadian hero and expecting him to deliver all the answers is perhaps a failing of my own.

“It's not only happening in hockey, it's happening in football and baseball and other sports,” O'Ree said recently to Elisabeth Fraser of CBC News. “Now we're concentrating on hockey because the sport has very few black players and players of colour playing in it. I'm disappointed in that there's still players out there that have to look at a person and judge them by the colour of their skin.

“We've taken one step forward and two back. I believe we're working in the right direction, but it's going to take a long time. It's not going to happen overnight.”

Wayne Simmonds, Devante Smith-Pelly and Kelsey Koelzer of the Professional Women’s Hockey Players Association all cite O’Ree as an inspiration, the latter two directly crediting him for their interest in the sport. O’Ree’s fight against racism and ability to prevail through some horrific abuse during the Civil Rights Era is something that shouldn’t be forgotten, and his induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2018 was long overdue—with many people stating during the film that they assumed he had already been admitted long ago.

Today is a great day for @NHL and the game of hockey! I’m very proud to be an NHLer! @thehockeyhalloffame #HHOF pic.twitter.com/nnhMaq3SxS

— P.K. Subban (@PKSubban1) June 26, 2018

Koelzer cited the importance of representation in hockey, and with Akil Thomas emerging as a national hero for Canada during the World Juniors, Quinton Byfield projected to go No. 2 overall in this summer’s draft, and K’Andre Miller about to graduate to the New York Rangers—to go along with a record number of black players in the NHL—the future looks bright.

Willie is well worth your time, if you get a chance to see it. O’Ree’s journey to the NHL is remarkable and though it doesn’t fully address some of the structural problems facing the sport, his own advocacy for further inclusion and anti-racism in hockey is a legacy worth admiring.

More NHL coverage from Yahoo Sports