Win, Lose, Compromise, and Keep Fighting: The WGA Contract Battles That Still Remain

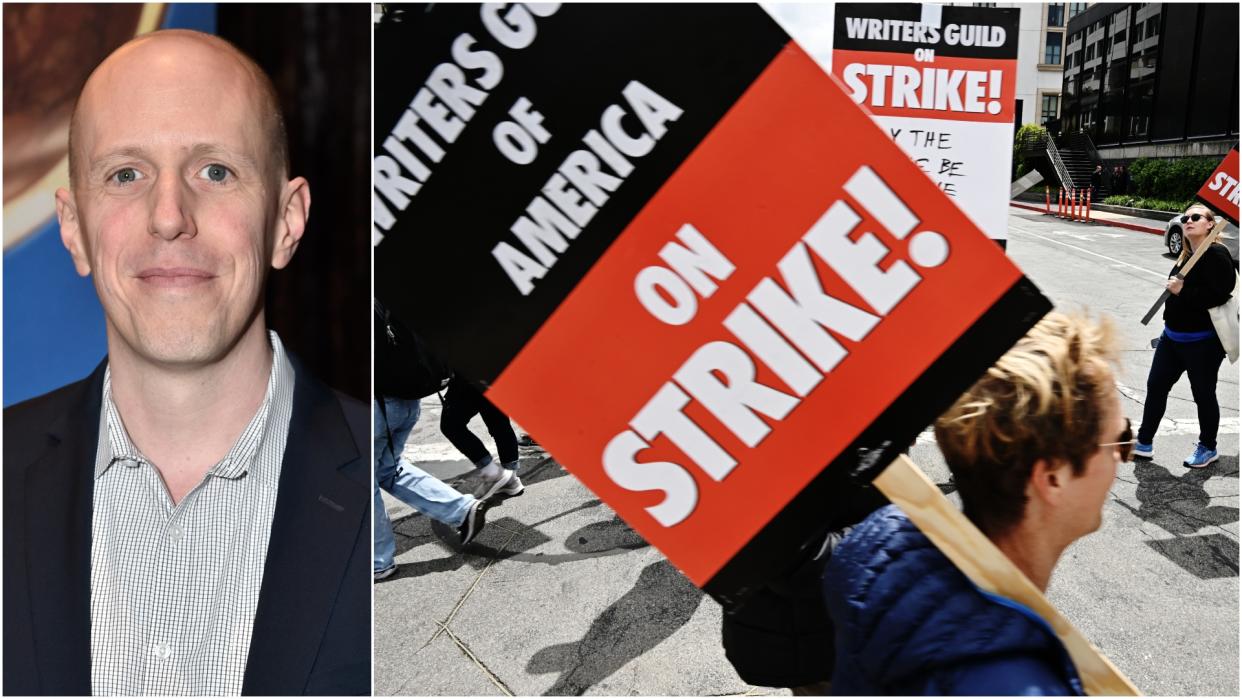

Win some, lose some. That’s how negotiations go, and it’s how the WGA and AMPTP settled their lengthy standoff. In an impressive feat of transparency, the WGA laid out its own strike receipts from start to finish. The strike is over, but “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” screenwriter and WGA committee member John August told IndieWire that doesn’t mean the guild stops fighting.

With AI, the guild won precedent: AI can’t replace a human worker, or drive down their wages or working conditions. And he described the fight for success-based residuals as “our first crack,” but the writers will use the next three years to figure out how well the model works.

More from IndieWire

The Pipeline Problems: Here's What Film and TV Production Looks Like When the Strikes End

SAG-AFTRA to Meet with AMPTP on October 2 Following End of Writers Strike

In an extended conversation with August over Zoom on September 27, the day after the contract details were released, he broke down the wins and the compromises, and where the WGA will need to keep pursuing its goals. “One of the great lessons of this contract,” he said, “is so many things we took as just the norms in Hollywood were revealed not to be norms, because companies just decided not to do them anymore. This contract was about really codifying those norms.”

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This fight has always been framed as an existential one for the future of writers and writing as a profession. How does this deal address those needs and provide a path for writers?

On every level, this move toward streaming and this new business model had come at the expense of our members. We needed to come up with proposals for a deal that would address all these issues. That was the broad, comprehensive thing we went to the AMPTP about, spent almost five months on strike about, and finally won for our members: meaningful gains across every sector of industry.

What is some of the reaction you’ve heard about the deal so far?

Excitement, euphoria, relief, surprise. On Sunday when we announced that we reached a deal, we couldn’t announce the details. We were still drafting the contract language and we didn’t want to get ahead of that. But last night when we could release the full details, it’s been amazing to see people respond to all the things that we’ve won: the protections in AI, a guaranteed second step for screenwriters, coverage for Appendix A writers on streaming, which was essential. Everyone recognized that across the board we’ve made huge wins and huge gains.

On minimum staffing and preserving the writers room, you didn’t get the full numbers that you wanted, but why does it still meet your goals?

All of our episodic proposals had to fit together and make sure that pay bumps — from moving from entry-level, staff-level jobs, up through story editor, up through writer-producer — were meaningful. Not just title bumps, but actual dollar bumps so that a person could grow in their career. A person who is 20 years into their career should not be earning the same as a person who just started.

We needed to make sure that in minimum staffing that there were actually enough bodies, enough people there to write those shows. I was talking with an animation showrunner who had an order for 30 episodes on his series, and it was just him. He was allowed to hire freelance writers who could do individual episodes, but there was no one else to help him make that show [and] those other writers were inexperienced to make shows. Minimum staffing was a crucial piece in making sure this all fit together.

How about the aspect of defining a showrunner as a writer? Why was that such an important distinction?

We would’ve had a great deal without that distinction in there, but one of the great lessons of this contract is so many things we took as just the norms in Hollywood were revealed not to be norms because companies just decided not to do them anymore. This contract was about really codifying those norms — the sense that there is a writers room, that you need to be paying people for the work they’re doing, and staff writers should be paid script fees for the episodes they write. It feels appropriate that the contract does acknowledge that the showrunner is a writer, and the showrunner is the writer who’s making decisions about staffing on the show. Is it crucial? No, but I think it is long overdue.

How did you arrive at the threshold for the success-based residual? How many writers’ projects will this impact?

This was a real challenge. A crucial thing for people to understand is writers who are working in streaming already had what’s called a fixed residual. A fixed residual is based on the length and the budget of a show — it’s a pre-calculated amount for the residual base. In this contract, we raised the residual bases and got significantly more money for when those shows are viewed internationally, which is incredibly important.

[Another] goal was to finally acknowledge that if something is a hit, the writers who wrote that hit deserve to be paid more residuals. That’s been true since the start of residuals. If I write “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” I should be paid for how successful “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” is. Back in the age of DVDs, it was per-DVD sold. We needed to acknowledge that and add it to the contract.

It ended up having to be a two-pronged attack. First, we needed transparency. We need to be able to see how successful shows were. What we ended up winning is the ability for the guild to go in and look and audit how successful shows are. That’ll help us form future policies and future goals for the next negotiation.

Even more crucially — this was the hardest-fought victory — was figuring out a system for a bonus paid to writers based on how successful that show is on the service. That threshold was set at 20 percent, so a show or movie that’s been viewed by 20 percent of a service’s subscribers gets a bonus payment based on the residual base. That’s huge.

The services love to brag “This is the Top 10 show in America” and if they’re willing to brag about those things, that should actually come with a check for those writers. It looks like now that will. How many shows or movies were impacted each year is still TBD. The companies across the table can give us some indication, but we won’t know fully until we have the transparency to back it up.

There’s still a confidentiality agreement that the guild has to abide by. Were you pushing for more transparency to make these numbers public?

Our fundamental goal is to break the seal and to break the myth that it was impossible for them to be sharing this information, and that’s what we were able to do. I understand these companies are competitors and they don’t want to reveal stuff they don’t want to reveal. But they need to tell the folks who make their shows how they’re faring. So yes, there’s gonna be confidentiality on individual programs — but in the aggregate, we’ll be able to share with our members what we’ve learned and we’ll be able to make better decisions down the road about how this works. Also, having broken the seal will enable other creators, other producers, other talent to ask for more transparency and a bigger cut of things, which is important.

Was there debate about whether to do it as total views rather than a percentage?

Everything was a negotiation. A certain number of views on Peacock isn’t going to translate well into views on Netflix because Netflix is just a much, much bigger service. If somebody has to have 50 million views to get the bonus, no show on Peacock was ever going to be able to hit that. Our goal was to make sure that we are getting as many of our writers these bonuses as possible. A percentage of viewership was a way to do that.

What about for features? This doesn’t impact streaming movies made for a budget below $30 million.

I mostly work with features, so there’s the frustration that a movie is a movie is a movie. We shouldn’t pretend that an $80 million Netflix movie is the same as a $3 million Hallmark movie. They’re completely different models. Our initial proposal was that any movie budgeted over $12 million should be treated like a theatrical feature with all those terms. We didn’t get there, but we were able to lower that budget cap to $30 million and greatly improve how much the writers working on films made for streaming are going to get.

The residual formula for streaming features, but also with these success-based residuals and improved foreign residuals, get you much closer to where you were in a theatrical feature from the start. Not a total victory, but a huge improvement.

The reality is that most films of a certain size made from streamers are done under theatrical terms anyway because the streamers want the ability to put it in theaters. So this is really protecting against the future rather than changing much of what’s happening on the ground right now.

Why was adding a guaranteed second step for features so crucial?

When a writer is hired to write a screenplay, they are delivering the very best script they can. But so often, what they’re asked to do is: “Okay, before we officially turn this in, can you do a little more work, a little more work, a little more work?” All that free work ends up being months of actual unpaid labor. W

When I started as a writer, you were hired not just do a single draft; you had a built-in rewrite. They would say, “This is how much we’re paying for the first draft, this is for your rewrite.” They were asking for much less free work because they knew they had a whole other draft already on the books for you. It gave the writer some breathing room, but also makes sure you’re going to be paid more promptly.

The move to one-step deals, where there’s not that guaranteed second step, was really a scourge on writers — particularly for writers who are earning closer to the minimums. This guaranteed second step makes sure that those writers are going to have another crack at things. They’re going to be able to turn that first draft in sooner and then know that they’ll have another draft ahead of them and plan their lives a bit better.

How does the WGA deal go beyond what the DGA got with AI? How does this protect writers, and what were the compromises made to allow studios to still experiment with it?

I think all the noise we made about AI got folks in the DGA thinking about AI as well. The deal they made on AI ended up being, I think, a nicer, fuller version of “We’re going to keep talking about it,” but it didn’t offer a lot of protections. It said that AI is not a director, but it didn’t really go much further than that.

So when we came back to the table, it was important that what we clearly defined that AI is not a writer, that material generated by AI is not source material. But we went further and said that as a writer, you can choose to not use AI tools and they can’t force you to use them. If they’re handing us material that is generated by AI, they have to tell you it is generated by AI because some people have ethical issues and don’t want to touch that at all. That was crucial for us as well.

The studios came to us and said there may be cases where we don’t want writers to use AI. We said “Sure, we get that,” because studios sometimes have their own AI concerns over copyright and infringement. That sounds fair. That sounds reasonable.

On the issue of using our materials to train their models, that’s a contentious thing. We have to remember that we are doing work for hire. The companies own the copyright on things that we write. In theory, they should be able to do whatever they want with them — except as part of our deal, we’ve held on to certain rights and controls over certain things, and we didn’t want to give away any of those controls or our ability to litigate in the future. In the deal we reached, we did not give up any of those things. The guild reserved its right to assert any claim under applicable law or MBA over training. This is still a live issue.

Basically, I think it’s been misreported that we did consent to their using our material on other things. We did not. We said we reserve the right to assert that we still can have legal claims, arbitration claims over use of our material based on other things that we’ve held onto.

So it’s still a point of contention down the road. Is that a compromise?

It’s a compromise in the way that both sides are saying no one is giving up anything here, that we recognize this is a live and open issue, and the law is changing. So neither side of us is going to give up anything here in this contract, which is the perfect place for us to have ended up.

If you look at the companies doing AI right now — Microsoft, Facebook, OpenAI — none of those companies are part of our MBA. We’re not negotiating with them. There’s all sorts of other places that are doing things like this and some of these tools are open source. Maybe other countries are doing things with these tools that are trained off of our material. In some cases, the studios and the writers guild are going to be on the same side trying to protect work from being scanned into these models. It’s a complicated situation.

Fortunately, the guild has so many tools beyond just this MBA. In the last three months we’ve testified before the Office of Copyright and to the FTC about AI issues. Our president Meredith Stiehm testified before a Senate committee — right next to Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk and the head of OpenAI — about not just writers’ concerns but artists’ concerns about the use of our material to train stuff. We’re going to be fighting on every front in the years ahead to make sure we can control the rights over the things we should be able to control and that our stuff isn’t going to be used against us to train replacements.

Are there aspects in which you felt the WGA did make some concessions?

One of the things about our union is that we were so transparent. You can see the things that we were after, the many places we got them and the few places we didn’t. A few examples would be — this sounds obvious, but a writer who works through post-production needs to be paid as a writer who works through post-production. Some studios are not doing that. We have a lot of active arbitration cases on these things and we were trying to codify it in this agreement that if a showrunner is working through post, they need to be paid as a showrunner through post. That’s a thing we didn’t get in this contract, but that doesn’t mean we won’t be fighting for it on other fronts.

In many cases, we didn’t get the numbers we were going for in initial asks. But that doesn’t mean they weren’t huge game changers for our members.

Best of IndieWire

Nicolas Winding Refn's Favorite Films: 37 Movies the Director Wants You to See

The Best LGBTQ Movies and TV Shows Streaming on Netflix Right Now

Unsimulated Sex Scenes in Film: 'Nymphomaniac,' 'Brown Bunny,' 'Little Ashes,' and More

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.